Social vulnerability as the intersection of tangible and intangible variables: a proposal from an inductive approach

La vulnerabilidad social en la intersección de variables tangibles e intangibles: una propuesta desde un abordaje inductivo

DOI: 10.22458/rna.v12i2.3773

1University of Valencia, Associação A3S; CEOS.PP, Valencia, España

Email: maffagomes@gmail.com

2University of Valencia, Associação A3S; CEOS.PP; ISCAP, Polytechnic Institute of Porto, Valencia, España

Email: analuisa.martinho@gmail.com

Received: February 25, 2021

Accepted: September 13, 2021

ABSTRACT:

This paper aims to analyse social categories related to vulnerability through a qualitative approach. This reflection is based on sociology of poverty, and social vulnerability, with contributions from the theory of intersectionality and the concept of social disintegration. Through this approach, social vulnerability is a plural concept that results from the intersection of social positions, life experiences, and skills. The characteristics of social groups in situations of vulnerability will be examined through interviews with social workers in social economy organisations. The outcomes indicate that social vulnerability results from the intersection of socio-demographic and economic factors that weaken the educational and professional trajectory of people in situations of vulnerability, particularly about their social and emotional competencies. From this inductive approach, we propose an intersection of tangible and intangible variables to characterize the complex profile of people experiencing social vulnerability.

KEYWORDS:

VULNERABILITY, SOCIAL DISINTEGRATION, SOCIAL ECONOMY.

RESUMEN:

Este artículo propone analizar las categorías sociales relacionadas con la vulnerabilidad por medio de un abordaje cualitativo. Esta reflexión está basada en la sociología de la pobreza y la vulnerabilidad social, con los aportes de la teoría de la interseccionalidad y el concepto de la desintegración social. A través de este abordaje, la vulnerabilidad social es un concepto plural que resulta de la intersección de posiciones sociales, las experiencias de la vida y las habilidades. Las características de los grupos sociales en situaciones de vulnerabilidad serán examinadas por medio de entrevistas con trabajadores sociales en organizaciones de economía social. Los resultados indican que la vulnerabilidad social resulta de la intersección de factores socio-demográficos y económicos que debilitan la trayectoria educacional y profesional de las personas en situaciones de vulnerabilidad, particularmente acerca de sus competencias sociales y emocionales. Desde este abordaje inductivo, proponemos una intersección de variables tangibles e intangibles para caracterizar el perfil complejo de las personas en situación de vulnerabilidad social.

PALABRAS CLAVE:

VULNERABILIDAD, DESINTEGRACIÓN SOCIAL, ECONOMÍA SOCIAL.

RÉSUMÉ:

Le but de cet article est d'analyser les catégories sociales liées à la vulnérabilité au moyen d'une approche qualitative. Cette réflexion est basée sur la sociologie de la pauvreté et la vulnérabilité sociale, avec des apports de la théorie de l'intersectionalité et le concept de la désintégration sociale. A travers cette approche, la vulnérabilité sociale est un concept pluriel qui résulte de l'intersection de positions sociales, des expériences de vie et des habiletés. Les caractéristiques de groupes sociaux dans des situations de vulnérabilité seront examinées au moyen d'entrevues avec des travailleurs sociaux dans des organisations d'économie sociale. Les résultats indiquent que la vulnérabilité sociale provient de l'intersection de facteurs sociodémographiques et économiques qui débilitent la trajectoire éducative et professionnelle de personnes dans des situations de vulnérabilité, en particulier concernant leurs compétences sociales et émotionnelles. A partir de cette approche inductive, nous proposons une intersection de variables tangibles et intangibles pour caractériser le profil complexe de personnes en vulnérabilité sociale.

MOTS-CLÉS:

VULNERABILITE, DESINTEGRATION SOCIALE, ECONOMIE SOCIALE.

RESUMO:

Este artigo propõe uma análise das categorias sociais relacionadas à vulnerabilidade através de uma abordagem qualitativa. Esta reflexão tem como base a sociologia da pobreza e a vulnerabilidade social, com as contribuições da teoria da interseccionalidade e do conceito da desintegração social. Através desta abordagem, a vulnerabilidade social é um conceito plural decorrente da intersecção de posições sociais, as experiências da vida e as habilidades. As características dos grupos sociais em situação de vulnerabilidade serão examinadas através de entrevistas com assistentes sociais em organizações de economia social. Os resultados indicam que a vulnerabilidade social resulta da intersecção de fatores sociodemográficos e econômicos que fragilizam a trajetória educacional e profissional das pessoas em situação de vulnerabilidade, principalmente quanto às suas competências socioemocionais. A partir dessa abordagem indutiva, propomos uma intersecção de variáveis tangíveis e intangíveis para caracterizar o perfil complexo de pessoas em situação de vulnerabilidade social.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE:

VULNERABILIDADE, DESINTEGRAÇÃO SOCIAL, ECONOMIA SOCIAL.

Towards an intersectional theory of social vulnerability

Recovering the legacy of French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu's theory (1989), we find that social reality is organized in spaces defined by logics of power, with social roles and expectations. Poverty, characterized by people without power as a result of the privation of economic capital, is a prevalent phenomenon across all societies, so it must be anchored in a multidimensional perspective of analysis.

The study of poverty has its origins in Georg Simmel's text entitled “Der Arme” (The Poor), published in 1907, in which the author began by defining the social categories of “poor” and “poverty” through a assistential relation between them and the society where they live. In fact, Simmel argues that someone is not considered poor, until he/she is assisted/take care of (Simmel, 1998). This theoretical approach of Simmel is on the basis of more recent concepts, like social disqualification, as cited directly by the author itself in the introduction of the French version translated in 1998.

Poverty is not a static concept, as we can observe with the emergence of the so-called “new poverty” that goes beyond the analysis of exclusively economic dimensions. The “new poverty” corresponds to a complex and plural phenomenon linked to the precariousness of work, the increase of individualism, and the weakening of social ties (Paugam, 2006). Without resources to guarantee their subsistence, people in situations of poverty request social support that contributes to the construction of negative stereotypes that weaken their identity. More than a vulnerable economic condition, poverty corresponds to a specific social and identity status. For example, high levels of schooling have for many years almost offered “immunity” to experiencing situations of poverty, and in contemporary times accomplishing an academic degree is not synonymous with job integration or a non-precarious contract. With the economic crisis cycles, people with educational capital became, like any other group, vulnerable and potential beneficiaries of social benefits.

Serge Paugam (2006) emphasizes the processes of social disqualification that are characterized by a decline in social and professional belonging of people who are not in a precarious situation from an economic point of view. The theory of social disqualification looks at poverty as a social construction and social groups stereotyped with this condition, have their social status. The author argues that “poverty is the symbol of social failure and often translates into human existence, through moral degradation” (p.24).

Social exclusion describes the decline of the bonds that individuals maintain with society. Social exclusion is “the extreme phase of the process of marginalization, understood as a 'descending' path, along which there are successive ruptures in the relationship of the individual with society” (Costa, 1998, p. 10). However, not all forms of exclusion explain a lack of access to all basic social systems. For example, someone can be excluded from some social systems and not from others. Poverty does not always imply that there is also social exclusion, as a person in a situation of poverty may have support networks (family, friends). Therefore, poverty and social exclusion are “different realities and they do not always coexist”1 (Costa, 1998, p. 10). Poverty can be defined as a form of social exclusion, but not the other way around.

As a complex phenomenon, vulnerability can affect social groups that, following their condition of exclusion/marginality, do not benefit from fundamental human rights. It can happen either by ignoring their existence, by inhibition, by ignorance about the form of access, or by the complexity to apply for the benefits. It is a polysemic concept used in several scientific disciplines (Alwang et. al., 2001) that can not be reduced to institutional and administrative categorizations. Mostly marginalized groups are categorized as migrants, people with disability, NEET, ex-convicts, etc. This simplification often translates into a set of stereotyped traits that don't consider the diversity of identity factors and the experiences of each person (Lima & Trombert, 2017).

Vulnerability can also be a condition associated with individuals who are in the labour market and who, however, are subject to precarious work situations and low wages. Despite this, individuals who exercise a professional occupation have a lower risk of social vulnerability (Marques et al., 2016).

In addition to access to social rights and working conditions, age is also considered an explanatory variable for the degree of vulnerability of individuals and social groups. In this analysis and for other social groups, it is important to consider other variables such as social support network, family dynamics, material resources, income, level of education, or the length of time in a vulnerable situation. Groups that are in a situation of vulnerability are those that are exposed to new social risks such as children, young people, working women, families with young children, and people with reduced skills or who do not fit the new work paradigm (Zimmermann, 2017).

The concept of vulnerability lacks stability and consensus in terms of the indicators that contribute to its classification. Contributing to this situation is the fact that vulnerability is not only changing in time and space, but is also dependent on the interaction of different variables, which are not mutually exclusive.

It is from this perspective that we follow the contributions of the theory of intersectionality used in different contexts of research and intervention, precisely to shape the interactions and relationships between the different master categories that are sex/gender, class, ethnicity, religion, nationality, sexual orientation, and disability (Nogueira, 2017). Here we use it to understand and characterize vulnerable groups. The intersectional approach doesn't cover the set of individual life paths; however, it allows coupling, from the theoretical and intervention point of view, contributions that integrate the diversity of experiences and the nuances specific to the various issues under analysis, thus being an approach specific and more holistic (David-Bellemare & Williams, s.d, p. 13-14; Nogueira, 2017, p.141).

Work takes on a relative centrality in people's lives (Ramos, 2000; Vázquez, 2008) and is a structuring element in interpersonal relationships, between groups and organizations. It plays a guiding role in daily life, in interaction, and in people's identity and social position and also in obtaining income, enabling the acquisition of goods and services (Dias, 1997 as cited by Marques, 2000). Until the 1970s, when the economic paradigm shift took place, the central concern of professional integration focused on the transition to the job market, especially among young people. In the last decades there has been a change in the processes of transition to the labour market and that extends to various social groups.

We refer to the effects in line with the consolidation of the knowledge society, globalization, demographic aging, and the affirmation of the technological and digital revolution and which have broadened the typology of situations that tend to keep people away from work or a stable and dignified job.

Who are the most vulnerable groups? The answer to this question is complex and not watertight. The experiences of vulnerability are heterogeneous and result from the sociodemographic trajectories that place people more or less subject to exclusion processes (Costa et al, 2018). In this way, is there a range of vulnerability that combines tangible situations with intangible ones? Social groups in situations of vulnerability are social constructions whose meanings must include a previous note because their simplification may contribute to stereotypes that are indifferent to the specificities of identity and the life trajectories of each one (Lima & Trombert, 2017, p. 17). Intensive research shows that although this concept is widely used, it lacks debate and consensus in the field of social sciences. Law No. 4/2007 of the General Bases of the Portuguese Social Security System illustrates the lack of clarity regarding the concept when referring to the importance of social action for “social exclusion or vulnerability” and for “protection of the most vulnerable groups, namely children, young people, people with disabilities and the elderly, as well as other people in a situation of economic or social need” (Article 29). This definition is quite broad and so are its underlying social categories.

The social groups identified as most vulnerable vary over time, as can be seen by comparing the list of disadvantaged social groups in a study conducted at the end of the 20th century (Capucha, 1999) and in a study published in 2018 (Costa et.al, 2018). In the first study, and as an example, reference is made to: Long-term unemployed, single-parent families, young people at risk, drug addicts and ex-drug addicts, detainees and ex-prisoners, minority ethnic and cultural groups, people with low qualifications, members of circles of installed poverty, homeless people and people with disabilities. From the analysis of the problems for each of the ten identified groups, Capucha (1999) presents a categorization of them around four types of situations of vulnerability, namely: the weak qualifications and competences, the accommodation to installed poverty circles, the adoption of marginal lifestyle and different specific handicaps.

In the second study, the following social groups in situations of vulnerability are mentioned: poor workers, unemployed, informal caregivers, disabled for work due to illness, challenged and elderly people in a situation of vulnerability. Having followed an eminently qualitative approach, this study sought to perceive the self-perception of the situation of vulnerability from the narratives of the people themselves, with emphasis on reduced schooling, insufficient material conditions, precarious and fluctuating professional trajectories, health and well-being problems, weak network of sociability and insufficient social support in relation to needs.

According to the Commission Regulation (EU) No 651/2014 of 17 June 2014 declaring certain categories of aid compatible with the internal market, there are several categories of vulnerable adults (Official Journal of the European Union, 2014, p. 17) 'worker with disabilities' means any person who: (a) is recognised as worker with disabilities under national law; or (b) has long-term physical, mental, intellectual or sensory impairment(s) which, in interaction with various barriers, may hinder their full and effective participation in a work environment on an equal basis with other workers; 'disadvantaged worker' means any person who: (a) has not been in regular paid employment for the previous 6 months; or (b) is between 15 and 24 years of age; or (c) has not attained an upper secondary educational or vocational qualification (International Standard Classification of Education 3) or is within two years after completing full-time education and who has not previously obtained his or her first regular paid employment; or (d) is over the age of 50 years; or (e) lives as a single adult with one or more dependents; or (f) works in a sector or profession in a Member State where the gender imbalance is at least 25 % higher than the average gender imbalance across all economic sectors in that Member State, and belongs to that underrepresented gender group; or (g) is a member of an ethnic minority within a Member State and who requires development of his or her linguistic, vocational training or work experience profile to enhance prospects of gaining access to stable employment.

From the classical theories on social vulnerability, to the most recent studies, as well as European regulations, we can verify some trends. In fact, the characteristics that classify vulnerable groups only take into account tangible dimensions such as age, gender, nationality and ethnicity. Some authors integrate the important contribution of the theory of intersectionality in their analysis and categorization. The theory of intersectionality finds its origins in Anglo-American black feminism through its founder Crenshaw. Her approach appeals to the perspective of different dimensions of vulnerability that intersect with each other and that tend to affect individuals and social groups in different ways. Therefore, vulnerability results not only from a characteristic of a person, but from the sum of various positions and social roles he/she plays in society.

There is many evidence that corroborate the positive consequences of the social economy, not only for the economy as a whole, but also for the improvement of people's living conditions, with a focus on their inclusion, dignity and personal and professional empowerment. In the European Union, despite the high heterogeneity, the social economy represents a sector with a growing employment capacity (Borzaga, 2020; Borzaga, 2017; Laville, 2008a, p. 38). In Portugal, with regard to training for principles of management, innovation and entrepreneurship, on the one hand, and in their capacity for training and professional social integration, on the other, this in their job creation (Parente et. al, 2014; Sousa, 2012). Furthermore, the social economy represented, in 2016, 6.1% of paid employment, wages and total employment, increasing compared to 2013 and compared to the total economy. Paid employment in the social economy in health is 32.1% and in social services 29.8% (INE, 2018).

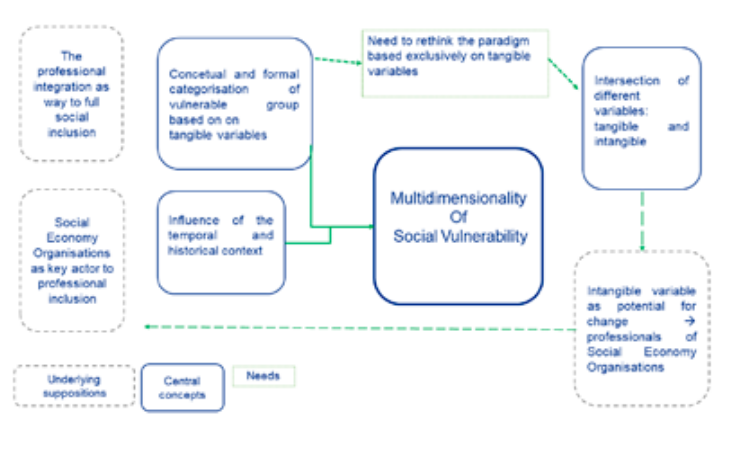

Although some authors integrate the perspective of intersectionality, we believe that it is necessary to deconstruct the paradigm based exclusively on tangible variables. So our analytic model (Figure 1) is based on the intersection of different variables: tangible and intangible ones.

Figure 1. Analytical model

Our analysis model is based on two underlying assumptions. The first one is that professional integration is a way to achieve full social inclusion and to access other human rights. The second assumption is based on the key-role of Social Economy organisations regarding socio professional inclusion of job seekers with complex needs and resources.

As mentioned, the concept of vulnerability has been based on tangible variables. We consider that it is necessary to rethink this paradigm and take into account the influence of the temporal and social context. So, our proposal is to consider social vulnerability as an intersection of different variables, tangible and intangible. The change in the life trajectory of vulnerable groups can happen through the effort made by social economy professionals in the intangible variables of vulnerable groups.

Methodology

This paper results from two works in progress. The study A focuses specifically on youth people and study B on adults that are part of social and labour (re)integration programs. Our objective is to characterize situations of vulnerability in Portugal linked to phenomena of “social disintegration” (Paugam, 2006), trough the perception of social workers that support people into social inclusion.

Although vulnerability is often analysed as a condition of specific social groups, we intend to reinforce the debate that focuses on the multidimensionality of the situation of vulnerability. This approach calls for a deconstruction of the vulnerability analysis paradigm itself, a changing condition throughout history and from society to society. It is also a condition influenced by specific social issues such as economic downturns. Even though it brings together recurrent characteristics that describe individuals in these conditions, it is not a closed concept and its attribution is not at all mechanical. The relevance of this reflection is reinforced, as we will see later, by the discourse of the technicians who follow disadvantaged people and the contributions of the technicians demonstrate the volatility of this condition.

The specific objectives are first of all to identify working age social groups that are in a situation of social vulnerability, justifying, based on the literature review, this condition. We focus our analysis on working age persons as it is also pertinent to understand, from the more macro point of view of the two ongoing research works, the relevance of the social economy in the socio-professional inclusion of these target groups. Therefore, we do not include children (people between 0 and 14 years old) and elderly (peoplo aged 65 and over).

Second, we intend to characterize these social groups based on the data collection carried out by professionals who support people in situations of vulnerability.

The concept of poverty, for example, describes the scarcity or the absence of material resources, emphasizing the condition of individuals' economic disadvantage. A methodological strategy based the content analysis of interviews conducted in study A with 15 Social Economy social workers2, and in Study B in 9 case studies3 of Work Integration Social Enterprises regarding the main characteristics of these social groups. Data collection was carried out between May 2019 and May 2020.

Preliminary results

We will now present the preliminary results, following the two studies - A and B. In each one we identify patterns in data collection and compare them between both studies. We also analyse uniqueness in each one of the studies.

In study A, the interviews with social workers mainly reveal tangible dimensions of social vulnerability, although they prefer to intervene with at-risk youth. We figure three social workers do not specify the existence of variables that explain the need for their monitoring, in other words, it is observed the distancing of these professionals from concepts which, according to them, contribute to the worsening of the situation of vulnerability of these target groups.

When asked about the characteristics of this social group, these interviewees do not mention indicators of social belonging, education, material resources, or socio-emotional status that could justify the need for their intervention. Says one social worker: “if you ask me what those kids are like, I always say they're distressed kids. They are kids who need help, who need time, who need things that sometimes we can't provide, but they are distressed” [E7].

Two other social workers refer to ambivalent characteristics that can define any social group, such as "they are people with whom you can create a very easy relationship, in terms of creating bonds this is already more difficult" [E09] and "curious and resilient” [E10].

The data points to the existence of six categories of analysis from which social workers characterize the social groups they support:

- the social workers mostly characterize the vulnerability of their target group through socio-emotional skills. This means that 18 references were identified in total in the moments of collection of information that point to this dimension. This includes the low self-esteem manifested in this discourse, for example, “they are not confident of themselves, they do not recognize themselves as having the skills to do anything that gives them some extra value. They don't have confidence or self-esteem” [E1] A high emotional fragility because “at an emotional level they have many needs” [E4]. Communication problems, “difficulty they have in expressing themselves, in saying what they feel and recognizing in others what they are feeling” [E2]. And yet the transversal absence of interests and apathy “has that history of thinking it's not worth it “that's what it is…”, conformism” [E07];

- socioeconomic context (n=11), namely the scarcity of financial resources to meet basic needs and accommodation in social houses or neighbourhoods that contribute to stereotypes and that affect the way others look at themselves. In this regard, one social worker says "they are unequal because they are born in the neighbourhood, this is, therefore, a condition at the outset [...] the neighbourhood is excluded from a territorial point of view [...] they have difficulty finding a job when they say they are from the neighbourhood" [E13];

- school performance (n=8,) and here we understand learning difficulties, low levels of education, and low expectations about their academic path;

- family support network (n=7), social workers who support young people emphasize this pattern, pointing to situations of negligence, and the absence of poorly defined family roles that make young people assume premature responsibilities associated with adulthood, such as caring for younger brothers. Says an insertion agent “they are young people with little accompaniment, they spend a lot of their time alone, taking care of themselves and often their siblings. Therefore, they are left to themselves […] ensure, for example, that the brothers eat” [E2];

- professional pathway (n=5) with precarious and irregular job experiences, coupled with low expectations regarding the possibility of attaining more stable and decent trajectories;

- ethnicity (n=6) “at school level it is a population with accentuated learning difficulties, caused by the fact that Portuguese is not the mother tongue, most do not speak Portuguese correctly and have many difficulties that end up reflected school performance)” [E04].

Another pattern identified was the cycle of poverty that these groups experience and which are difficult to break. A social worker says “there is a kind of snowball in these young people, especially here in this territory, and it is something that has been dragging on for years and years, that the story I tell now about a young person is almost the same one told by a young man who lived in this neighbourhood 10 years ago” [E05].

This finding that “they are in repeated cycles of poverty” [E1] and that they do not recognize themselves in a situation that they are not aware of is transversal to several statements and reveals a very great difficulty in contributing to the social inclusion of these groups.

The possibility of childhood poverty remaining unchanged into adulthood is high (Unicef, 2017, Diogo, 2021). Socioeconomic inequalities are difficult to break, especially in hereditary situations, which is why it is urgent to train professionals to adjust interventions to people's profiles, rather than to available resources.

Regarding to study B, focused on 9 case studies of different kinds of Work Integration Social Enterprises, we start to present, for each one, the main target-groups:

Table 4. Main target group of case studies

| Main target group | |

| Alfa | People with disabilities |

| Beta | People with mental illness |

| Gama | Unemployed people |

| Delta | Unemployed people in situations of high vulnerability |

| Kapa | People with disabilities |

| Lambda | Unemployed people |

| Omega | Unemployed people + People with disabilities + people with addictive behavior |

| Iota | Unemployed people |

| Zeta | Unemployed people |

Table 4 represents a simple classification on main target groups of case studies, identified in the Social Economy Organisation legal status. As we can see, the categories are not specific. For six of them, the main target group are simple unemployed people, four people with disabilities (including mental illness) and one person with addictive behaviour.

We will now present the data collected in each case studies, through interviews with the support team, and also observation of activities, mainly team meetings. Social workers from case studies identify characteristics around two main categories: tangibles and intangibles.

For tangibles categories, we put together the administrative characteristics, such as age, gender, employment status, beneficiaries of social welfare, disability, and mental illness. For illustrative purposes only, let's analyse the following four examples: i) for Delta case study the profile supported target groups is mainly male, aged over 40; ii) for Alfa case, working with young people with functional diversity, the coordinator explained that supported people have to be autonomous (for coming from home to work, for using bathroom, etc.); iii) for Lambda case, the profile is defined as mostly long-term unemployed people with low qualifications; iv) for Iota case, the focus is on young NEETs or long-term unemployed with a low level of education.

But, for all social workers those tangible characteristics are never the only ones. That's why they identify what we categorized as intangible issues. Social workers identify pathways of high inactivity, back and forth between employment and unemployment, and odd jobs in the informal economy "experiences of six months, a year, right? And very long periods outside the labour market that makes, well, at the level of the curriculum, not very attractive, for example" (E2 - Delta). There is a lot of precariousness both in school and in labour market pathways and specifically women who "since becoming pregnant, have become pregnant consecutively and have very low educational qualifications ... young people who have dropped out of education and have had very meagre professional experiences" (E2 - Omega).

Socio-emotional skills are also a common profile among the target group. Indeed, characteristics such as lack of trust in the labour market, in social work and even in him or herself are often mentioned by the interviewees: “It is here that the person gains confidence in himself [...] is to trust himself/herself again, to start again, isn't it? This question of skills is extremely important for that. Because people are completely discredited in the labour market, they no longer believe. [...] And so there is a very big discredit in the system here, um... and therefore, also situations of behaviour of companies that were not the best, that did not pay certain hours [...] there is a very big discredit in vocational training” (E2 - Iota). Also low self-esteem and a negative self-image, especially regarding the relationship of supported people with education and training, with discourses such as "I don't do well at school; my head doesn't work; I've never made it; [...] so, the problem is me" (E1 - Zeta). Associated with life paths marked by different difficulties, the target group presents a profile that reveals some emotional fragility. Some of them don't have a support system “it is a very emotionally unstable population […] There has already been a very big cut here in terms of family too, because of age and because family relationships too, many of them have worn out” (E5 - Omega).

Our empirical results and content analysis have uncovered unconventional categories that have seldom been mentioned in the literature.

Through this finding, based on an inductive approach - starting from observation and based on experience for the construction of knowledge - we identified the intersection of the tangible and intangible variables.

From this approach of association between predefined social categories and characteristics such as education, competencies, and emotions, we find that social vulnerability is not an “ideal type”, but a flexible category with a wide spectrum of reach.

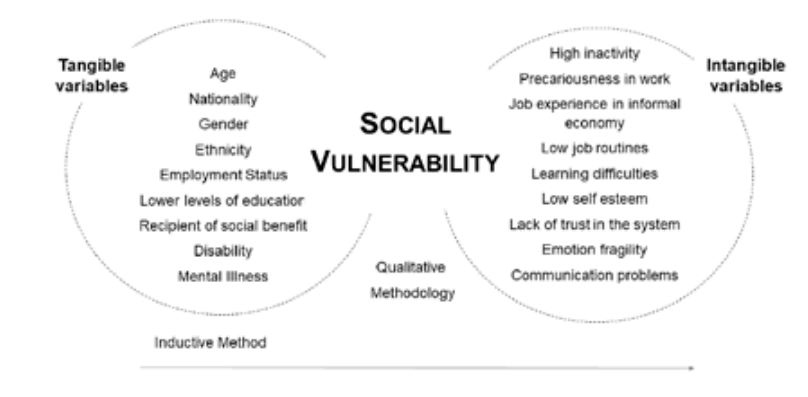

We propose to look at vulnerability as a phenomenon that results, as seen in Figure 2, from the intersection of tangible and intangible variables. Tangible variables are those that concern physical issues, with a reduced probability of being changed, or conditions categorized by employment and social protection, namely: Age, Nationality, Gender, Ethnicity, Lower levels of education, Employment Status, Recipient of social benefit, Disability, and Mental Illness.

The intangible variables are those that result from knowledge that comes from qualitative approach techniques (direct observation, interviews) such as life trajectories, emotions, expectations, and fears about the future, namely: High inactivity, Precariousness in work, Learning difficulties, Low self-esteem, lack of trust in the system, emotional fragility. Those variable were the most identified by social workers.

This is a complex proposal and requires a deep and subjective understanding of these social groups, which are more than shelving categories. Only through multidimensional and intersectional work is it possible to understand social vulnerability to build measures and public policies adjusted to their profiles.

For these reasons, understanding social vulnerability has become even more important in the course of this work, because it is considered that there are still analytical paths to explore and deepen. It is under this assumption that this proposal falls.

Figure 2. Multivariate proposal of social vulnerability

Conclusion

The results of our investigations demonstrate that there are sociodemographic variables (education, gender, age, employment status, ethnicity, and physical and mental condition) that point to a greater propensity for situations of vulnerability. The sociodemographic indicators that explain vulnerability are closely associated with economic cycles (Diogo, 2021) as can be seen in the analysis of education, age, and gender indicators in the periods between 2008 and 2020.

The tangible dimensions that explain vulnerability are closely associated with economic cycles, and intangible dimensions are associated with the intersection of different social, cultural and economic factors. At the same time there are intangible dimensions identified by social workers that not only corroborate some of the tangible variables but also reveal other elements that characterize these target groups. This propensity is even more evident through the crossing of variables, through an intersectional perspective.

As for the qualitative data, it is observed that the social workers, from Study A, who work with young people use intangible dimensions to refer to the vulnerabilities of these target group, while the social workers from Study B who work with adults, despite referring to intangible dimensions, use more often tangible dimensions. One of the regularities found in both studies is that in the intangible dimensions of vulnerability, frailty and/or absence of social and emotional skills are most frequently reported.

Although the tangible dimensions of the explanation of social vulnerability are relevant, the intangible dimensions assume greater importance in the discourse of social workers to describe these target group. The interviews also reveal that the intervention of social economy professionals focuses mainly on the intangible dimensions, as they constitute dimensions that can be changeable.

In general, the data points to intersectional dimensions of vulnerability. As said by Carmo (et. al, 2018, p.1) “although income represents a fundamental aspect, it does not exhaust the multiple dimensions that contribute to the production and the persistence of inequalities. These are characterized by their multidimensionality about a different set of variables, sectors, and systems”4.

Under Pereira and Batista (2010) it is argued that “actors with direct actions in social intervention critically exercise a questioning of the context(s) in which they work, and to which a clear awareness of some fundamental concepts can contribute a lot” (p.44). From the social workers' speeches presented, it seems that tangible categories are absolutely not enough to handle the complexity of vulnerability phenomena. In fact, all of our interviewees defined a diverse and complex profile of the target group, which cannot be boiled down to mere administrative categories. As mentioned by one social worker, these target groups are in a place of “social invisibility”. So it is not possible to homogenise a single profile, because there is a diversity of groups and individuals living under this “invisibility”.

However, it should be noted that the characterization of this target groups isn't limited to defining situations of vulnerability, but also positive dimensions such as resilience. Therefore, the perception that social workers have of these groups is strongly based on their resilience to adapt and transform their life trajectory.

NOTES

- Free translation from the authors.

- The interviews were codes by number from E01 to E15.

- The case studies were coded Alfa, Beta, Gama, Delta, Kapa, Lambda, Omega, Iota and Zeta.

- Free translation from the authors.

REFERENCES

ALWANG, J.; SIEGEL, P.B.; JORGENSEN; S. (2001): “Vulnerability: a view from different disciplines”, SP Discussion Paper, nº 0115.

BOURDIEU, P. (1989): O poder simbólico, Lisboa, Difel.

CAPUCHA, L., CASTRO, J.L, MORENO, C., MARQUES, A.S, ESPERANÇA, N. (1999): Grupos Desfavorecidos Face ao Emprego, Lisboa, Observatório do Emprego e Formação Profissional.

CARMO (org.) (2018): Desigualdades Sociais. Portugal e Europa, Mundos Sociais, Lisboa.

COMISSÃO PARA A CIDADANIA E IGUALDADE DE GÉNERO (CIG) (2017). Igualdade de Género em Portugal: Indicadores-chave 2017.

COMMISSION REGULATION (EU) No 651/2014 of 17 June 2014, Official Journal of the European Union, 2014.

COSTA, B. (1998): Exclusões Sociais, Cadernos Democráticos, Gradiva.

COSTA, S. (2018) (coord.): Trânsito Condicionado. Barómetro do Observatório de luta contra a Pobreza na cidade de Lisboa Fase III, Cadernos EAPN, nº23.

DAVID - BELLEMARE, E. & WILLIAMS, N. (n.d.): Pauvreté et précarité: une approche inspirée de l'intersctionnalité. Centre de santé et de services sociaux. Champlain-Charles-Le Moyne : Université de Sherbrooke.

DAVID - BELLEMARE, E. & WILLIAMS, N. (n.d.): Pauvreté et précarité: une approche inspirée de l'intersctionnalité. Centre de santé et de services sociaux. Champlain-Charles-Le Moyne : Université de Sherbrooke.

DIOGO, F. (coord.) (2021): A pobreza em Portugal. Trajetos e Quotidianos, Fundação Francisco Manuel dos Santos, ISBN 978-989-9364-22-5.

INSTITUTO NACIONAL DE ESTATÍSTICA (INE) (2019): Inquérito às Condições de Vida e Rendimento. INE.

LIMA, L. & TROMBET, C. (2017): Le travail de Conseiller en Insertion. Montrouge, ESF Éditeurs.

Marques, A. P. (2000). Repensar o mercado de trabalho: emprego Vs desemprego. Sociologia e Cultura 1. Cadernos do Noreste, Série Sociologia, Vol. 13 (1) 133-155.

MARQUES, T.; MATOS, F.; MAIA, C.; RIBEIRO, D. (2016): “Metrópoles em crise”, Atas do XV Coloquio Ibérico de Geografía: Retos y tendencias de la Geografía Ibérica, Múrcia.

MARQUES, T.; MATOS, F.; MAIA, C.; RIBEIRO, D. (2016): “Metrópoles em crise”, Atas do XV Coloquio Ibérico de Geografía: Retos y tendencias de la Geografía Ibérica, Múrcia.

NOGUEIRA, C. (2017): Interseccionalidade e psicologia feminista. Brasil: Editora Devires.

OECD (2018), Indicators of Immigrant Integration, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264307216-en (Accessed on 06 June 2021)

OECD (2021), Gender wage gap (indicator), doi: 10.1787/7cee77aa-en (Accessed on 05 June 2021)

PAUGAM, S. (2006): A desqualificação social. Ensaio sobre a nova pobreza. Porto: Porto Editora. ISBN 978-972-0-34856-2.

PERISTA, P.; BATISTA, I. (2010) : “A Estruturalidade da pobreza e da exclusão social na sociedade Portuguesa - conceitos, dinâmicas e desafios para a ação”, Revista Fórum Sociológico, nº 20 (II serie), pp. 39-46. http://sociologico.revues.org/165.

SIMMEL, G. (1998): Les Pauvres. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

UNICEF (2017), Narrowing the Gaps: The power of investing in the poorest chil- dren. New York: Unicef

ZIMMERMANN, A. (2017): “Social Vulnerability as an Analytical Perspective”, Discussion Paper No. 4: Social Vulnerability as an Analytical Perspective.

Tavares, Inês; Ana Filipa Cândido; e Renato Miguel do Carmo (2021), Desemprego e Precariedade Laboral na População Jovem: Tendências Recentes em Portugal e na Europa, Lisboa, Observatório das Desigualdades, CIES-Iscte