Año 22, N.° 46: julio - diciembre

2023

Technological

Tools to Develop Competences for the 21st Century: A Project to

Empower Students in the English Teaching Major at UNED

Marco Antonio Alvarado-Barboza *

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1932-3785

* Magister en Ciencias de la Educación con énfasis en

Administración Educativa de la Universidad de Costa Rica (UCR), de Costa Rica.

Licenciado en Docencia con énfasis en Enseñanza de Inglés de la Universidad

Estatal a Distancia (UNED), de Costa Rica. Bachiller en enseñanza de inglés,

UCR y bachiller en Enseñanza de inglés para I y II ciclo, UNED. Profesor de la

Licenciatura en Administración de la Educación de la UCR, y docente de la

Carrera de Enseñanza de Inglés de la UNED. Correo: antonio.alvaradobarboza@ucr.ac.cr

Abstract

Being

a «native digital», that is to say an individual who has grown up using Internet, computers and mobile

devices, and being an individual able to communicate ideas effectively

in a foreign language are definitely traits of a profile for the 21st

century. Society is requiring future English teachers to graduate with these

linguistic and technological competences to eventually equip them to provide

their pupils with meaningful learning experiences. The following article

intends to describe all the actions, stages and activities carried out in a

project about technological tools offered to students from the English Teaching

Major at Universidad Estatal a Distancia

(UNED) during the year 2021. The article presents a description of the process

followed and the information obtained through a questionnaire and a group

discussion applied to the participants. One important conclusion was that

projects with a hands-on perspective where students not only get information

from professors but need to practice, construct, and propose their own ideas

will always contribute to the participants’ development.

Key

words: Technology, teaching methods, workshops.

Recibido: 21 de julio de 2022

Aceptado: 7 de diciembre de 2022

Herramientas tecnológicas para desarrollar competencias

para el siglo XXI: un proyecto para empoderar a estudiantes de la carrera de

Enseñanza del Inglés en la UNED

Resumen

Ser un individuo «nativo digital», esto es, un

individuo que ha crecido usando la internet, las computadoras y los dispositivos

móviles, al igual que ser un individuo capaz de comunicarse en un idioma

extranjero definen muy bien el perfil del siglo XXI. La sociedad requiere que las

futuras personas docentes de lengua extranjera puedan graduarse con estas

competencias lingüísticas y tecnológicas para eventualmente capacitarlas para

que puedan proveer a sus estudiantes de oportunidades de aprendizaje

significativas. Este artículo describe las acciones, etapas y actividades

llevadas a cabo en el proyecto de herramientas tecnológicas que se ofreció a

estudiantes de la carrera de la Enseñanza del Inglés de la Universidad Estatal

a Distancia (UNED). El texto presenta la descripción del proceso llevado a cabo

y la información obtenida a través de un cuestionario y una discusión grupal

aplicados a las personas participantes. Se concluye que los proyectos en los

cuales las personas participantes no solo reciben información de profesores

sino que practican, construyen y proponen sus ideas, contribuirá en el

desarrollo de las personas participantes.

Palabras clave: Método de enseñanza, talleres,

tecnología.

Outils technologiques pour

développer les compétences pour le XXIème siècle: un projet pour autonomiser les étudiants de la filière d’Enseignement de l’Anglais à l’UNED

Résumé

Être un individu «enfant du numérique» signifie qu’il s’agit d’une personne

ayant grandi en utilisant l’internet, les ordinateurs et les appareils mobiles, ainsi que d’être capable de communiquer dans une langue étrangère; tout ceci définit

très bien le profil du XXIème siècle. Par conséquent, la société actuelle demande que les futurs enseignants de langue étrangère finissent leurs études avec

ces compétences linguistiques

et technologiques acquises pour éventuellement se former plus afin de fournir à leurs apprenants des opportunités d’apprentissage significatives. Cet

article décrit les actions, les étapes et les activités menées dans le projet d’outils technologiques qui a été offert aux

étudiants de la filière d’Enseignement de l’Anglais à l’Université de l’État à Distance (UNED). En ce cas, on décrit le processus mis en œuvre et l’information obtenue à travers un questionnaire et d’une discussion groupale administrés aux sujets participants. Finalement, on a conclu que les projets dans lesquels les personnes peuvent aller au-delà de recevoir de l’information de la part des enseignants, ils contribuent au développement de ces personnes participantes car elles peuvent

pratiquer, construire et proposer leurs idées.

Mots-clés: méthode d’enseignement,

ateliers, technologie.

Introduction

Mankind

has always expressed a desire to learn new languages. The first attempts to

learn a foreign language in Costa Rica dates to the XIX century when Latin was

introduced. After that and due to influences from different societies and

telecommunications, French and English started to take place. Then, the latter

became the most important one because of the geographical, economic, political,

and cultural boundaries[1].

In

1935, an educational reform took place and the teaching and learning of English

was considerably transformed. Native speakers and Costa Ricans who have studied

and lived abroad were the ones in charge of facilitating the learning process.

Although they «master» the language, they did not have any formal training for

teaching. Due to this lack of formal teaching training, the Universidad de

Costa Rica (UCR) started its English teaching program in 1954. The methodology

used was the Audiolingual method.

From

1978 to 1990, the Ministry of Public Education eliminated formal and official

study plans and, instead, sent teachers a guide with a list of books to use and

units to cover in class. However, in 1990, because of an urgent change, new

study plans took place and directed the attention to a more communicative

methodology. These new plans thrive for new objectives, meaningful learning

contexts and more effective ways of evaluating students’ outcomes. The new approach is now the Communicative

Approach.

In

1977, under the government of President Daniel Oduber Quirós and according to

Law 6044 – March 3, Universidad Estatal a Distancia (UNED) was officially created as a High-Education

institution specialized in teaching through social communication means. It is

pioneer in Latin America with a distance learning modality[2]. Nowadays, UNED promotes

different levels of study programs, extension and research, and intensive use

of Information and Communication Technology (ICT´s) in its pedagogical model.

Regarding

the teaching of English as a foreign language (TEFL), UNED started training

teachers in 1997 because of a direct request from the Ministry of Public

Education that required immediate training of English teachers for the

elementary levels. Those teachers would come to ease the need of trained

professionals in Costa Rican schools. Once the agreement was over in 1999, UNED

decided to continue pursuing more efforts by developing and elaborating its own

English Teaching major[3].

The

first formal study plan dates to 2005 where different blocks of subjects were

put together. The diplomado plan integrated language

courses (Grammar, Conversation, Phonetics and Written Expression), teaching and

assessment courses (Didactics, Planning, Principles of Assessment, Didactic

Resources and Teaching Seminar), and complemented with general courses in

Spanish (Humanities, Curriculum, Pedagogy). The Bachelor´s program included

some language, teaching, and literature courses as well. No course on ICT´s was

part of the plan neither for the Diplomado plan nor

for the Bachelor´s one. The only course related to Technology in the English

major was part of the Licenciatura plan placed in

block K[4].

Teaching

and technology around the world

Norway

was one of the first countries in the world to include Information and

Communication Technology (ICT) within the national curricula in compulsory

education. In 2006 the Norwegian Ministry of Education and Research introduced

a new educational reform; the Knowledge Promotion reform; which included a new

curriculum in compulsory and upper secondary education (1st-13th

grade). The reform emphasized five basic competence aims considered equally

important, and one of those was to develop digital skills. Consequently,

teacher ability to provide learning opportunities in digital competences for

their pupils was highlighted. Moreover, the use of ICT in teaching and learning

became widespread in Norwegian schools[5].

Authors Joke Voogt & Natalie Pareja from

University of Twente in their article: 21st Century Skills Discussion Paper

state:

It is without a

question that ICT has a primary place when talking about 21st century skills.

The development of technology is not only regarded as an argument for the need

of new skills by all frameworks, but it is also associated to a whole new set

of competences about how to effectively use, manage, evaluate, and produce

information across different types of media. With more or less detail, all

frameworks refer to the three domains of what Anderson (2008) refers to as

‘applied ICT literacy’, namely: a technical domain (related to the basic

operational skills needed to use ICT), a knowledge domain (which refers to the

use of ICT with a particular knowledge related purpose) and an information

literacy domain (related to the capacity to access, evaluate and use

information).[6]

María

del Carmen Pegalajar[7] regarding teacher training

in the use of ICT states «those tools enable personal development, successful

activity completion and enjoyment of situations that call on one’s own

individuality, as well as fully and actively participating in activities in

one’s environment. What is more, devices of this type facilitate the

development of varying forms of expression and knowledge enhancement».

Authors

Llorent-Vaquero, Tallón-Rosales

y Heras-Monastero comment on their comparative study with students from Spain

and Italy regarding the Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) and

declare that

ICT´s are present

in almost all fields of society. These tools have generated important changes

and advances that have been introduced to our daily routines, slowly

integrating into our everyday lives until, in some situations, we have come to

depend on their use. In this technological context, being able to function

successfully in the digital field or develop digital competence is essential.[8]

Charles

Musarurwa implemented ICTS in Zimbawe

at the CITEP (College Information Technology Enhancement Programme)

and found that teacher educating students have a significant role to play in

the sustained application of ICT in schools. Therefore, declares Musarurwa «it is imperative that they are exposed to

effective use of ICT in their training. By integrating ICT as a learning

resource during regular classes, lecturers are exposing students to innovative

ways of learning»[9].

Nowadays

in India, teaching is becoming one of the most challenging professions where

knowledge is expanding rapidly and much of it is available to students as well

as teachers at anytime and anywhere. As education is primarily directed towards

preparing teachers, the quality of teacher education depends on the teacher

trainee's abilities and skills. The N.C.F. 2005 had also highlighted the

importance of ICT in school education and it also stated that «ICT if used for

connecting children and teacher with scientist working in universities and

research institutions would also help in demystifying scientist and their work»[10]. Therefore, teachers have

to accept the demands of modern world and modify their old concepts and methods

according to the needs of learners, otherwise teachers will become outdated in

the coming future and it will deteriorate the quality of education. There is

widespread belief that ICT can and will empower teachers and learners for

teaching-learning processes to develop their creativity, problem-solving

abilities, informational reasoning skills, communication skills, and other

higher-order thinking skills. ICT is not only used to enhance learning but also

important for a teacher to be comfortable using to ensure that students get the

full advantages of educational technology. Teaching with technology is

different than teaching within a typical classroom.

The

inclusion of ICT resources into teaching strategies constitutes a variable that

favors the growth of the learning efficiency, having a positive impact on the

student, but also on the teacher’s activities declared authors Gorghiu and Pascal on their article «Enriching the ICT

competences of university students»[11].

In

recent years, authors Garzón et al reported that «information and communication

technologies (ICTs) have entered society, causing numerous changes to the

social and economic levels, and without any doubt, to the educational one»[12]. They continue saying

that the reality of its arrival has led to a change in educational plans, whose

lines needed to be adapted to an innovative training where culture and digital

practice is predominant. ICTs permeate our daily lives, and their use is

becoming a fundamental requirement for insertion and promotion in the

workplace, for learning autonomy, and for encouraging the practice of active

citizenship.

As

is evident, the use of ICT is essential in education to prepare students for

the demands of the modern world. In 2014, the Ministry of Public Education of

Costa Rica embraced new trends in teaching and learning by adopting the Action

Oriented Approach as the core curriculum. The new plan was officially launched in

2017 and gradually introduced in first and seventh grade. The primary objective of this new curriculum was

to graduate students in sixth grade with a A2 level of proficiendy

and B2 for students graduating from eleventh grade according to the Common

European Framework for Languages.

This

curriculum was designed in an era in which technology plays an increasingly

important role. Professors and students of the English teaching major recognized

that while students were making progress in their linguistic performance, they

lacked technological skills. Courses, academic activities, and society itself

were longing for efforts from the university to help students improve and

maximize their capabilities by being trained in technology and XXI century

skills.

As

a result, the Cátedra Enseñanza

del Inglés developed a Research-Teaching Project

during second and third quarters of 2021, aimed at providing current students

in the English Teaching for I and II Cycles major with meaningful opportunities

to explore, comprehend, and develop competences for the 21st century

by interacting and designing technological tools.

Therefore,

the objective of this article is describe the process developed during the

implementation of the project «Technological Tools to Develop Competences for

the 21st Century» offered to students from the English Teaching

Major at UNED during the year 2021.

Methods

The

article uses a qualitative approach since the purpose is to describe the

process developed in the implementation of the project. As Dörnyei[13] explains qualitative

research «involves data collection procedures that result in open ended,

non-numerical data which is then analyzed primarily by non-Statistical Methods».

The project was developed over two quarters with students of the English

teaching for I and II cycle major, from different campus at UNED. The students

participated in workshops designed to teach them how to use different tools

that can be used when teaching.

Participants

In

the first phase of the project, 12 students participated; comprising 10 women

and 2 men. All participants were taking the diplomado

and the bachelor’s degree from the English teaching for I and II cycle major.

The participants could choose a schedule for the workshops from two options.

The first option was Monday and Wednesday from 5:30 p.m. to 7:30 p.m., and the

second option was on Saturday from 8:30 a.m. to12:30 p.m. Six students chose

the first schedule and the other six chose the second schedule.

During the second phase four participants

could not continue with the workshops due to working commitments. They were replaced

with four new participants. The new students chose the Monday and Wednesday

schedule. Thus the first schedule had a total of 7 students while the second

schedule had four students. Table 1 presents the student’s relevant background

information such as their assigned number, sex, age, schedule and the campus

where they study.

Table

1. Information of the participants

|

Student |

Sex |

Age |

University

Campus |

|

1

V |

Female |

34 |

Desamparados |

|

2

M |

Female |

22 |

San

Carlos |

|

3

C |

Female |

38 |

Puntarenas |

|

4

A |

Female |

35 |

Liberia |

|

5

J |

Male |

32 |

Desamparados |

|

6

S |

Female |

26 |

Puriscal |

|

7

A |

Male |

41 |

Orotina |

|

8

R |

Female |

30 |

Palmares |

|

9

N |

Female |

32 |

Nicoya |

|

10

N |

Female |

47 |

Upala |

|

11

M |

Female |

39 |

Ciudad

Neilly |

|

12

C |

Female |

27 |

Monteverde |

|

13

K |

Female |

48 |

Palmares |

|

14

S |

Female |

35 |

Desamparados |

|

15

D |

Female |

28 |

Cartago |

|

16

K |

Female |

47 |

Alajuela |

Source:

Alvarado-Barboza, 2022.

Instruments

Two

instruments were used to gather information from the participants regarding the

satisfaction of the project. The first instrument was an online questionnaire that

consisted of four open-ended questions related to the tools presented during

the workshops, their opinions on the methodology employed, the professor`s

performance and any recommendations they might have for the second quarter.

Besides, two closed-ended questions were included that asked participants to rade the usefulness of the tools studied during the

workshop and their interest in participating in the next quarter. Brown as cited

by Dörnyei define questionnaires as «any written

instrument that present respondents with a series of questions or statements to

which they are to react either by writing out their answers or selecting from

among existing answers»[14]. The questionnaire was administered

at the end of the second quarter in 2021 using Google Forms and it was sent to

the students via email.

The

second instrument was a focus group interview. According to Dörnyei

the focus group interviews is «a collective experience of group brainstorming,

that is participants thinking together, inspiring and challenging each other,

and reacting to the emerging issues and points»[15]. Participants could

express their ideas at the end of the second period about the project and

aspects to improve.

Results

and discussion

Development

of the project

The

project was developed in two quarters. Each quarter had three phases:

organization of the project, didactic activities, and evaluation of the

project.

In

the first phase «Organization of the project» during the first quarter,

the first step was the students’ registration. An informed consent was sent

to the students with the instructions and obligations related to the

participation of the project. The second step was to design the project with

the corresponding objectives, contents, methodology, timetable, materials,

evaluation, and outcomes expected.

In

the second phase «didactic activities» the students attended various workshops.

During the exploratory virtual sessions, the facilitator demonstrated the use

of the online tools such as Canva and Zoom for creating videos. These sessions

were conducted using the zoom app.

After

the workshop, the participants had to prepare a draft of a video using the

presented tools (Canva or Zoom). Then, the facilitator and the participants had

online sessions in which the facilitator provided feedback and participants

clarified doubts about the tools. The facilitator used the rubric shown in Table

2 to assess the drafts.

Table

2. Rubric used to evaluate the video drafts

|

Performance Level |

Needs Improvement |

Satisfactory |

Excellent |

|

|

Video content and organization |

The video lacks a central theme, clear point of view, and logical

sequence of information. Much of the information is irrelevant to the overall

message. 0-4 points |

Information is connected to a theme. Details are logical and

information is relevant throughout most of the video. 5-7 points |

Video includes a clear statement of purpose. Events and messages are

presented in a logical order, with relevant information that supports the

video’s main ideas. 8-10 points |

|

|

Creativity |

The video is not creative. 0-4 points |

The video needs more creativity. 5-7 points |

The video is very creative and catches the audience attention. 8-10 points |

|

|

Mechanics |

The text and/or audio has 4 or more grammar or spelling errors. 0-4 points |

The text and/or audio has 1-2 grammar or spelling errors. 5-7 points |

The text and/or audio has no grammar or spelling errors. 8-10 points |

|

|

Production |

Video is of poor quality. There are no transitions added or

transitions are used so frequently that they detract from the video. There

are no graphics. 0-4 points |

A variety of transitions are used, and most transitions help to

explain the content. Most of video has good pacing and timing. Graphics are

used appropriately. 5-7 points |

Video runs smoothly. A variety of transitions are used to assist in

communicating the main idea. Shots and scenes work well together. Graphics

explain and reinforce key points in the video. 8-10 points |

|

|

Length (4 to 5 minutes) |

Too long or too short. 0-4 points |

The video last almost the time proposed. 5-7 points |

The video achieves the time proposed (4 to 5 minutes). 8-10 points |

|

|

Comments |

Language comments |

|||

Source:

Alvarado-Barboza, 2022.

After

receiving feedback, students improved their drafts to create the final

version of the video. Then, they uploaded it to UNED’s platform: APRENDE U. The

same process was used with the second theme, which involved the design of

digital presentations using tools such as Powtoon and

Mentimetter.

At

the end of the quarter, students participated in an academic forum where they applied

the knowledge they had acquired to solve various situations related to technological

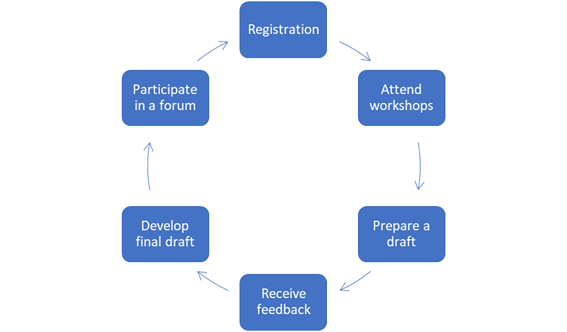

tools (Figure 1).

Figure

1. Activities developed by the students in the first quarter

Source:

Alvarado-Barboza, 2022.

In

the Figure 1 it is observed the activities that students developed in the first

quarter. For the evaluation of the project, students completed a

questionnaire. The questionnaire covered themes related to the opinion about

the tools, the usefulness of the tools, the methodology used during the

project, the professor’s performance during the workshops, the interest to

continue with the project and possible recommendations. It helped to make

decisions to improve the second part of the project in the following quarter.

In

the second quarter, after feedback from students was received, it was decided

to change the methodology used for the learning of the new tools. During this

transition, four students did not continue. A new registration had to be done

and four students substituted them. The second part of the project was prepared

similarly to the first quarter, but there were changes in the didactic

activities. One important change was that the projects were focused on

educational purposes. It helped to contextualize more the projects the

participants had to develop.

The methodology used during the workshops was

similar throughout both quarters. The facilitator demonstrated the use of the

tools which for the second quarter were Padlet, Genially and Google Classroom. Then,

students worked on their projects. They had to design a Padlet and upload the

material to UNED’s platform APRENDEU. Finally, students presented their

projects to both the facilitator and other participants providing and receiving

feedback. The table used for the feedback is presented in the Table 3.

Table

3. Table used to give feedback

|

Student: |

Group: |

|

Comments |

Language comments |

Source:

Alvarado and Brizuela, 2022.

After

the feedback students had to upload the final version of the project. This

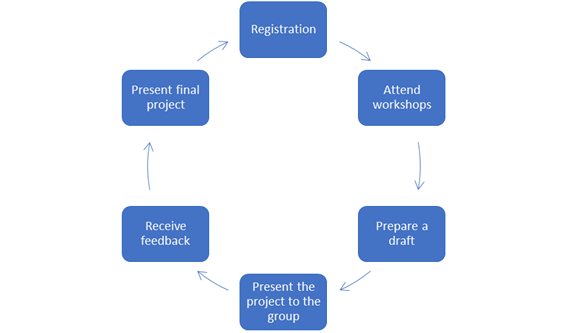

methodology was used with the tools Genially and Google Classroom (Figure 4).

Figure

4. Activities developed by the students in the second quarter

Source:

Alvarado-Barboza, 2022.

For

the evaluation of the project in the second quarter, students participated in a

group discussion. The facilitator gave students the opportunity to talk about

the aspects they liked and did not like about the project, also students provided

recommendations for improvement regarding methodology.

Students’

opinions

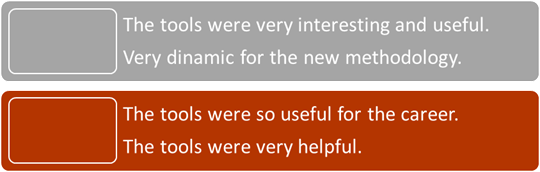

The

project was very successful for the students as all the participants found the

tools presented during the project to be very useful for their learning. Some

of the comments expressed in the questionnaire are presented in the Figure 5.

Figure

5. Students’ opinion about the tools

Source:

Alvarado-Barboza, 2022, based on the questionnaire applied to participants.

As

shown in Figure 5, students expressed that the tools were highly useful,

dynamic, and helpful. The tools provided them with the opportunity to be

prepared for a new context in which technology plays an increasingly important role

every day. According to LaToya et al.

technological

advancements have led to changes in the expectations placed on K-12 teachers.

Teachers are now expected to better equip students with 21st-century skills,

making it important to understand teachers' beliefs about the role of

technology in teaching and learning and the skills their students need to be

successful.[16]

Participants

considered these tools as significant since they were able to analyze how the

interaction with these tools will help them to improve the quality of their

classes. In the presentations of their projects, the participants could

demonstrate how the tools were useful in English teaching environments and they

were able to include in their presentations interactive games, videos, music,

audios and materials for students with curricular accommodations.

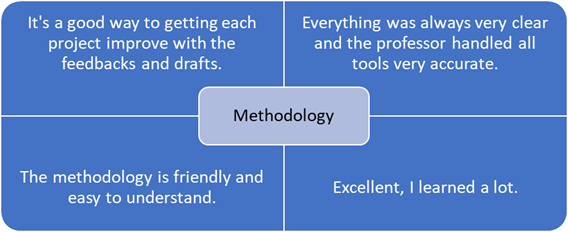

The

participants also provided their opinions about the methodology used during the

project. Some of the opinions about the methodology are presented in the Figure

6.

Figure

6. Opinion about the methodology used during the project

Source:

Alvarado-Barboza, 2022, based on the questionnaire applied to participants.

The

methodology used helped students to explore the apps with the facilitators’

help. Then, students could interact with the tools on their own to develop

their projects, but also students had the opportunity to present their projects

and to receive feedback during the process. This methodology facilitated the

participants learning since it was developed step by step. Authors Dmoshinskaia et al. comment on the importance of providing

and receiving feedback from peers and say:

Peer assessment is

being used more and more in education. Its growing popularity is due in part to

the trend of making educational processes in general, and assessment processesin particular, more active and student-centered.

Giving and receiving peer feedback is seen as an important vehicle for deep

learning.[17]

The

methodology used helped the participants to see how the tools worked, the

requirements, the difference between free and paid versions, and the use they

can give them for the teaching process. Participants were also able to register

and interact with the tool to design their own project. Besides, as Dmoshinskaia et al.[18] and the students

mentioned the feedback process was very significant for deep learning.

Participants were able to see their projects from different perspectives and

they could reflect about the teaching and learning process.

One

important aspect to consider was that students were able to evaluate the

project at the end of the first phase in order to improve the project for the

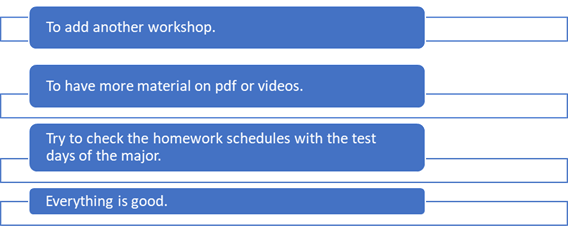

second phase. Some of the observations given are presented in the Figure 7.

Figure

7. Recommendations for the project

Source:

Alvarado-Barboza, 2022, based on the questionnaire applied to participants.

The

participants were very satisfied with the tools, methodology and facilitator.

However, they made some recommendations in aspects of time. For example, one

participant mentioned that she would have liked to have more workshops because

she was learning a lot. Another participant mentioned the idea of more videos

or PDF documents. In this case, all the sessions were recorded and uploaded to

APRENDEU platform, so that participants could see and review what was studied.

A

third recommendation was made in terms of administrative procedures since the

project needed to be scheduled taking into consideration the participants’

dates for exams and homework at UNED. For the second phase, students’ dates and

assignments were considered when making the chronogram. It was a difficult

process since the assignments at UNED for students from the profesorado

and bachelor’s degree from the career of English teaching at I and II cycle is

very demanding.

Final

conclusions

1.

Students from English Teaching major can consolidate their linguistic competences

as well as maximize XXI century skills through projects implemented by the coordination

in which they can use English to communicate their ideas and learn

technological tools that will eventually empower them to facilitate the

teaching-learning process with elementary level students.

2.

Projects with a hands-on perspective where students not only get information from

professors but need to practice, construct, and propose their own ideas will

always contribute to the participants’ development.

3.

Enabling meetings with participants where individualized feedback is provided

to them to shape their personal projects is a key to promote self-regulation,

self-assessment and self-improvement of students.

4.

The ages from the participants was in a range from 22 years to 47 years. For the

oldest students the use of technology was very difficult, but they were guided

in a simple way to make the process easier and not frustrating. It means that

the methodology used was effective to achieve the goal of the project.

5.

Participants were able to interact with a variety of tools, but at the same

time the reflection process they did about the teaching of English was very new

for them. They not only learned how to use a tool, but also how to use it for a

specific English objective. It helped participants a lot for their future

practicum at the English Major and for their future job as teachers.

6.

This was the first time that this project was put into practice. For this

reason, the feedback given by the participants would help to improve the implementation

of future projects with similar characteristics.

Formato

de citación según APA

Alvarado-Barboza, M. A. (2023). Technological

Tools to Develop Competences for the 21st Century: A Project to

Empower Students in the English Teaching Major at UNED. Revista Espiga 22 (46).

Formato de citación según Chicago-Deusto

Alvarado-Barboza, Marco Antonio. «Technological Tools to Develop Competences for the 21st

Century: A Project to Empower Students in the English Teaching Major at UNED». Revista Espiga 22, n.° 46 (julio-diciembre,

2023).

References

Córdoba-Cubillo, Patricia, Rossina

Coto-Keith y Marlene Ramírez Salas. «La enseñanza del inglés en Costa Rica y la

destreza auditiva en el aula desde una perspectiva histórica». Actualidades

en Educación 5, n.° 2 (2005): 1-12. https://revistas.ucr.ac.cr/index.php/aie/article/view/9153/17525

Dmoshinskaia, Natasha, Hannie Gijlers y Ton de Jong. «Giving feedback on peers’ concept maps in an inquiry

learning context: The effect of providing assessment criteria». Journal of

Science Education and Technology 30 (2021): 2021.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10956-020-09884-y

Dörney, Zoltán. Research Methods in applied linguistics.

Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011.

Egeberg, Gunstein, Greta Björk Gudmundsdottir, Ove Edvard Hatlevik,

Geir Ottestad, Jørund Høie Skaug,

and Karoline Tømte. The Digital State of Affairs in

Norwegian Schools. Nordic Journal of Digital Literacy (2012).

https://www.idunn.no/doi/10.18261/ISSN1891-943X-2012-01-07

Garzón-Artacho,

Esther, Tomás Sola-Martínez, José Luis Ortega-Martín, José Antonio Marín-Marín

y Gerardo Gómez-García. «Teacher training in lifelong learning – The

importance of digital competence in the encouragement of teaching innovation». Sustainability 12, n.° 7 (2020):

https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072852

Pascale,

Lucia, Gabriel Gorghiu y Laura Mónica Gorghiu. «Enriching the ICT

competences of university students – a key factor for their success». Conferencia

pronunciada en 3rd Central and Eastern European

LUMEN, Chişinău, Moldavia, del 8 al 10 de junio de

2017.

O’Neal,

LaToya J., Philip Gibson y Sheila R. Cotten.

«Elementary school teachers’ Beliefs about the role of technology in 21st -Century

teaching and learning». Computers in the School. Interdisciplinary Journal

of Practice, Theory, and Applied Research 34, n.° 3 (2017): 192-206. https://doi.org/10.1080/07380569.2017.1347443

Llorent-Vaquero, Mercedes,

Susana Tallón-Rosales y Bárbara de las Heras-Monastero.

«Use of information and communication

technologies (ICTs) in Communication and collaboration: A comparative study

between university students from Spain and Italy». Sustainbility

12, n.° 10 (2020): https://doi.org/10.3390/su12103969

Musarurwa, Charles. «Teaching with and learning through ICTs in Zimbabwe’s

teacher education colleges».US-China

Education Review A 7 (2011): 952-959.

Mora,

Yinnia. Plan de Estudios de la Carrera Diplomado,

Bachillerato y Licenciatura en Enseñanza el Inglés para I y II ciclos. San José: UNED, 2008.

Pegalajar-Palomino, María del Carmen. «Teacher training in the use of ICT for

inclusion: Differences between early childhood and primary education». Procedia

– Social and Behavioral Sciencies 237 (2017):

144-149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2017.02.055

Programa Estado de la Nación. Sexto

informe estado de la educación. San José:

PEN / Servicios Gráficos,

2017.

Thakur, Nabin. «A study on implementation of techno-pedagogical

skills, its challenges and role to release at higher level of education». American

International Journal of Research in Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences,

2 (15-154), 2015.

Voogt, Joke y Natalie Pareja Roblin. 21st century skills. Discussion paper. Enschede: Universidad de Twente,

2010. http://opite.pbworks.com/w/file/fetch/61995295/White%20Paper%2021stCS_Final_ENG_def2.pdf

Universidad

Estatal a Distancia. «Historia». Acceso: 28 de junio de 2023.

https://www.uned.ac.cr/historia