Chemistry of essential oils of the shrub Lippia alba (Verbenaceae)

from Mexico and Costa Rica

Carlos

Chaverri1,2![]() , Feliza Ramón-Farías3

, Feliza Ramón-Farías3![]() & José F. Cicció1,2

& José F. Cicció1,2![]()

1. Universidad de Costa Rica, Escuela de Química, San José 11501-2060, Costa Rica; cachaverri@gmail.com, jfciccio@gmail.com

2. Universidad de Costa Rica, Centro de Investigaciones en Productos Naturales (CIPRONA), San José 11501-2060 Costa Rica.

3. Universidad Veracruzana, Facultad de Ciencias Biológicas y Agropecuarias. Apartado Postal 177, 94500, Córdoba, Veracruz, México; felizarf@hotmail.com

Received 2-II-2022 Corrected 23-V-2022 Accepted 24-V-2022

DOI: https://doi.org/10.22458/urj.v14i2.4005

|

ABSTRACT: Introduction: Lippia is a Verbenaceous genus of flowering plants, which has about 200 species, distributed throughout the southern USA, Mexico, and Central America to South America. Objective: To study and compare the chemical compositions of the essential oils of L. alba growing in Mexico and Costa Rica. Methods: The essential oils were obtained by hydrodistillation in a Clevenger-type apparatus. The chemical composition of the oils was analyzed by capillary GC-FID and GC-MS using the retention indices on a DB-5 type capillary column in addition to mass spectral fragmentation patterns. Results: A total of 65 compounds were identified in the essential oil samples from both countries, accounting for 96,5-98,1% of the total amount of the oils. The main constituents of the Mexican sample were 1,8-cineole (22,3%), myrcenone (11,2%), myrcene (10,9%), (E)-ocimenone (10,7%), (Z)-ocimenone (7,5%), and sabinene (6,8%), while for essential oil from Costa Rica the major compounds were myrcenone (30,4%), 1,8-cineole (21,4%), myrcene (11,0%), hedycaryol (4,4%), and sabinene (4,3%). Samples from both countries can be classified as belonging to chemotype “tagetenone”. Lippia alba (strong form) from Costa Rica produces essential oil that differs from all other essential oils of L. alba studied to date because it contained the sesquiterpenoids hedycaryol and the isomeric alcohols α-eudesmol, β-eudesmol, and γ-eudesmol. Conclusion: L. alba (strong form) from Costa Rica can be classified as a new subtype of the chemotype “tagetenone” (chemotype II).

Keywords: Lippia alba, essential oil, myrcenone, 1,8-cineole, myrcene, (E)-ocimenone, (Z)-ocimenone, Mexico, Costa Rica.

|

RESUMEN. “Química de los aceites esenciales del arbusto Lippia alba (Verbenaceae) de México y Costa Rica.” Introducción: Lippia (Verbenaceae) consta de ca. 200 especies, distribuidas a través del sur de Estados Unidos, México, América Central, el Caribe y hasta el Cono Sur de América del Sur. Objetivo: Estudiar y comparar la composición química de los aceites esenciales de L. alba de México y Costa Rica. Métodos: La extracción de los aceites se efectuó mediante hidrodestilación con un equipo Clevenger modificado. La composición química del aceite se analizó mediante las técnicas GC-FID y GC-MS. Para la identificación de los constituyentes se calcularon los índices de retención obtenidos en una columna capilar tipo DB-5, y se estudiaron los espectros de masas de cada constituyente. Resultados: Se identificaron en total 65 compuestos en las muestras de ambos países, correspondientes a un 96,5-98,1% de los constituyentes totales de los aceites. Los componentes mayoritarios de la muestra de aceite mexicana fueron 1,8-cineol (22,3%), mircenona (11,2%), mirceno (10,9%), (E)-ocimenona (10,7%), (Z)-ocimenona (7,5%) y sabineno (6,8%); y los compuestos mayoritarios de la muestra de L. alba de Costa Rica fueron mircenona (30,4%), 1,8-cineol (21,4%), mirceno (11,0%), hedicariol (4,4%) y sabineno (4,3%). Ambas muestras estudiadas en este trabajo se clasifican como pertenecientes al quimiotipo “tagetenona”. Lippia alba (forma fuerte) de Costa Rica produce un aceite que se diferencia de todos los otros aceites de L. alba estudiados a la fecha porque contienen el sesquiterpenoide hedicariol y los alcoholes isoméricos α-eudesmol, β-eudesmol y γ-eudesmol. Conclusión: L. alba (forma fuerte) se puede considerar como un nuevo subtipo perteneciente al quimiotipo “tagetenona” (quimiotipo II).

Palabras clave: Lippia alba, aceites esenciales, mircenona, 1,8-cineol, mirceno, (E)-ocimenona, (Z)-ocimenona, México, Costa Rica.

|

Verbenaceae is a family of flowering plants from the order Lamiales, with a worldwide distribution but mainly in tropical and subtropical areas, with 34 genera and about 1 100 species of herbs, shrubs, and some trees (The Plant List, 2013). The genus Lippia is composed of ca. 200 species and about 60 infraspecific taxa (Munir, 1993; Atkins, 2004). Lippia alba is an aromatic perennial shrub that grows up to 2 meters with serrate, opposite, alternate leaves with small flowers purple to violet, with pink or white variations, occurring in leaf axils. This plant is cultivated for its commercial importance in Argentina, Brazil, Costa Rica and Guatemala (Cicció & Ocampo, 2006; Ricciardi et al., 2009). In the American Continent, the geographical distribution of Lippia alba (Mill.) N. E. Br. ex Britton & P. Wilson (Cicció & Ocampo, 2010) covers the Neotropics in the dry forests of Central America, the humid regions of the Caribbean islands, and South America to the Amazon Rainforest. This species is present as well in subtropical dry climates and subtropical regions of North America (northern Mexico and Texas) and South America (Southern Cone). This broad distribution conditioned the species to present a wide genetic variability, in order to occupy the diverse natural habitats available, a situation that leads to their adaptation to the various biogeographic regions (Cicció & Ocampo, 2010; Amaral et al., 2017). The biogeographic distribution of chemotypes (or “chemovarieties”) of L. alba in continental America and in the Caribbean responds to environmental factors and to genetic conditions of the species. Chemotypes, according to Polatoğlu (2013), are “organisms categorized under the same species that have differences in quantity and quality of their component(s) in their whole chemical fingerprint that is related to genetic or genetic expression differences”. In relation to the ecological factors, the evidence indicates the existence of chemotypes in biogeographic regions (Cicció & Ocampo, 2010). The presence of biotypes in various regions of the American Continent helps the species to adapt more easily to the conditions at each site, varying significantly the composition –both quantitative and qualitative– of essential oils, enhancing the fitness of the progenies. There is natural polyploidy within the species, a mechanism of plant speciation that results in morphological plasticity and the presence of several chemotypes (Reis et al., 2014). Lopes et al. (2020) studied genetic relationships and polyploid origins in the L. alba complex, and they found that there is an association between morphological characters and ploidal level but the patterns of genetic and chemical variation are not related to geographical distribution. Biotypes found in the subtropical regions of America (both in the north and in the south) are characterized by pendulous branches, and it is assumed that this feature is a response to periods of low temperatures. By contrast, the plants of biotypes that grow in the tropics (between Tropic of Cancer and Tropic of Capricorn, ca. 23° 27’ north and south) have branches with upright growth (Cicció & Ocampo, 2010). Indeed, the presence of biotypes of L. alba with its own characteristics in the whole continent, which have distinctive morphological differences, correlated with variations in the essential oil composition (intraspecific variation) that can be grouped into chemotypes, based on the genetic background of the plant. As result, the presence of a certain chemotype probably reflects the ability of the species to respond to various abiotic conditions of the ecological environment (geographical coordinates, altitude, climate, soil, sun exposure, humidity). The species develops its own genetic characteristics, which are maintained (with variations) when moving to new biogeographic sites. This can be attributed to intraspecific genetic variations that occur in the various populations of L. alba.

Lippia alba is commonly named in some regions of Mexico as pitiona, salvia de Castilla and hierba tapón. In Costa Rica, this plant is known as juanilama, yerba dulce, and cat mint, this last name especially in Limón province (Segleau, 2001). This species is extensively used as traditional medicine in tropical America (Morton, 1981; Gupta, 1995; Gilbert et al., 2005). In Costa Rica, the leaf and flower infusions are taken as stomach sedatives, antispasmodic, for diarrhea, colitis, peptic ulcers, and gastritis; expectorant, sudorific, and emmenagogue (Núñez, 1975; Segleau, 2001). On the Costa Rican marketplace, the plant is sold in the commercial form of sachets for infusion and as a part of some specialized products for the treatment of colds and congestion of airways, while the alcoholic extract –frequently accompanied by extracts of Cassia reticulata Willd. and Capsicum annuum L.– is used topically to relieve rheumatic pain (Cicció & Ocampo, 2004; 2006). In Honduras, the decoction of the leaves is used for coughs, sore throats and chest, fever, stomach ache, and grippe (House et al., 1995). In Guatemala, the leaf decoction is used in the treatment of respiratory conditions (asthma, colds, laryngitis, and cough), and the alcoholic extract is used in friction against colds and respiratory congestion (Cáceres, 1996). The medicinal applications for flu and colds are classified as recommended by Farmacopea Vegetal Caribeña and it is considered non-toxic (Germosén-Robineau, 2005). Hennebelle et al. (2008) reported that the main medicinal usages of this plant are against digestive, respiratory, and cardiovascular diseases and as a sedative.

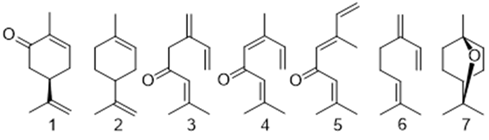

In Costa Rica, there are two natural chemotypes: one is called sweet form, defined by the presence of high levels of the cyclic monoterpenoids carvone (1) and limonene (2), and the other one is called strong form, characterized by the presence of the acyclic polyunsaturated monoterpenoids myrcenone (3), (Z)-ocimenone (4), (E)-ocimenone (5), myrcene (6), and the cyclic compound 1,8-cineole (7), as main constituents (Cicció & Ocampo, 2004; Ricciardi et al., 2009) (see numbered chemical structures in Fig. 1). The biogeographical situation of Costa Rica serves as a land bridge between North and South America. The sweet form probably came from South America (occurs in Colombia, Venezuela, and Brazil) and the strong form probably came to Costa Rica from Mexico and Guatemala.

Fig. 1. Structures of monoterpenoids identified from Lippia alba chemotypes of Costa Rica.

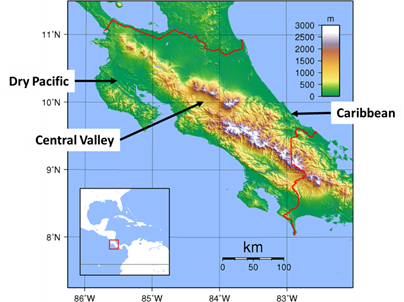

Geographical differentiation of the populations was observed with a predominance of the sweet form in the southeast humid Caribbean region of Costa Rica and the strong form in the northwest dry Pacific side of the country and in the Central Valley with different habitat conditions. The Caribbean region (Atlantic), located between the mountains and the Caribbean Sea, in the southeast region of Costa Rica, receives an average of 4 100mm of annual rainfall and has an average annual temperature of 22°C (Gómez, 1986). The northwest Pacific region (Dry Pacific), limited by the Pacific Ocean and the Guanacaste Mountain Range (see Fig. 2; Topographic Map of Costa Rica, 2007) presents a mean annual rainfall of 2 000mm and annual temperature of 27°C. The Central Valley, delimited by the Central Mountain range, the foothills of Talamanca, and the slopes of San Miguel, has an average annual rainfall of 2 400mm and an average annual temperature of 20°C in its middling altitude of 1 100m (Gómez, 1986).

Fig. 2. Topographic map of Costa Rica. From “Costa Rica Topography.png,” by Sadalmelik. (2007, September 16). Wikimedia Commons (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/file:Costa_Rica_Topography.png). In the public domain.

There are several studies concerning the chemical constituents of L. alba. This species contains iridoids (von Poser et al., 1997; Barbosa et al., 2006; Hennebelle et al., 2006a; Filho et al., 2007; Timóteo et al., 2008), aromatics (phenylethanoid/phenylpropanoid compounds) (Barbosa et al., 2006; Hennebelle et al., 2006b; Timóteo et al., 2008), flavonoids (Hennebelle et al., 2006b), biflavonoids (Barbosa et al., 2005), and triterpenoid saponins (Farias et al., 2010). The L. alba essential oils have been extensively investigated and showed large differences in their compositions. Many papers have been published which referred to at least eight different chemotypes, defined by the accumulation in the essential oils of characteristic monoterpenoid metabolites (Hennebelle et al., 2006a; Ricciardi et al., 2009; Cicció & Ocampo, 2010).

The present paper investigates the chemical composition of the essential oils obtained by hydrodistillation from samples of L. alba growing in the Mexican state of Veracruz and in the Central Valley of Costa Rica.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

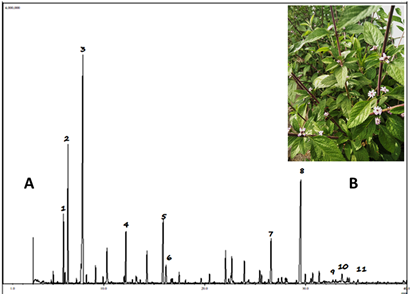

Plant Materials: Flowering aerial parts of L. alba (Verbenaceae) from Mexico were collected in Coscomatepec, Veracruz state, in July 2011, at an altitude of 1 600m. A voucher specimen was deposited at the Herbarium of the University of Costa Rica (F. Ramón F. 312, USJ 100089). The sample from Costa Rica was collected in San Rafael, Montes de Oca, Province of San José (9°56’37.00’’N, 84°01’01.80’’W), at an altitude of 1 335m (see Fig 4). A voucher specimen was deposited in the Herbarium of the University of Costa Rica (USJ 70698). The plants were air-dried prior to hydrodistillation operation.

Isolation of the essential oils: The oils were isolated by hydrodistillation at atmospheric pressure, for 3h using a Clevenger-type apparatus. The distilled oils were collected and dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate, filtered, and stored at 0-10°C in the dark, until further analysis. The yield of the pale yellowish oil was 0,19% (v/w) in fresh plant material.

Gas chromatography (GC-FID): The oils of Lippia alba were analyzed by GC-FID (gas chromatography with flame ionization detector) using a Shimadzu GC-2014 gas chromatograph. The data were obtained on a poly (5% phenyl-95% dimethylsiloxane) fused silica capillary column (30m x 0,25mm; film thickness 0,25μm), (MDN-5S, Supelco), with a LabSolutions, Shimadzu GC Solution, Chromatography Data System, software version 2.3. Operating conditions were: carrier gas N2, flow 1,0mL/min; oven temperature program: 60-280°C at 3°C/min, 280°C (2 min); sample injection port temperature 250°C; detector temperature 280°C; split 1:60.

Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS): The analyses by gas chromatography coupled to mass selective detector were performed using a Shimadzu GC-17A gas chromatograph coupled with a GCMS-QP5000 apparatus and CLASS 5000 software with Wiley 139 and NIST computer databases. The data were obtained on a poly (5% phenyl-95% dimethylsiloxane) fused silica capillary column (30m x 0,25mm; film thickness 0,25μm), (MDN-5S). Operating conditions were: carrier gas He, flow 1,0mL/min; oven temperature program: 60-280°C at 3°C/min; sample injection port temperature 250°C; detector temperature 260°C; ionization voltage: 70 eV; ionization current 60μA; scanning speed 0,5s over 38-400amu range; split 1:70.

Compound identification: Identification of the components of the oils was performed using the retention indices which were calculated in relation to a homologous series of n-alkanes, on a poly (5% phenyl-95% dimethylsiloxane) type column (van Den Dool & Kratz, 1963), and by comparison of their mass spectra with those published in the literature (Adams, 2007) or those of our own database. To obtain the retention indices for each peak, 0,1μL of an n-alkane mixture (Sigma, C8-C32 standard mixture) was co-injected under the same experimental conditions reported above. Integration of the total chromatogram (GC-FID), expressed as area percent, has been used to obtain quantitative compositional data.

RESULTS

From the hydrodistilled oils, a total of 65 compounds were identified by means of GC-FID and GC-MS techniques, accounting for 96,5-98,1% of the total composition of the essential oils. The compounds identified in the oils of L. alba (Table 1) are listed in order of elution on an MDN-5S column. Table 1 also includes the relative percentages of single components; their experimental retention indices (RI) with reference to a homologous series of linear alkanes (C8-C32) and for comparison purposes, previously published values are also included (Lit. RI). Lippia alba gave oils that were predominantly terpenoid in nature, with mostly monoterpenoids (80,3-83,0%).

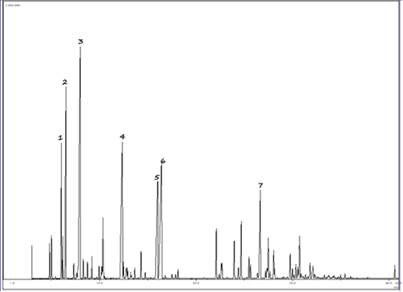

The Mexican essential oil contained 30 different monoterpenoids with 1,8-cineole (22,3%), myrcenone (11,2%), myrcene (10,9%), (E)-ocimenone (10,7%), (Z)-ocimenone (7,5%), and sabinene (6,8%) as major constituents. [See the total ion chromatogram (TIC) in Fig 3]. The regular acyclic monoterpenoids that constitute the oil represented 43,5%, the p-menthane monoterpenoids about 25,1%, and 11,0% the rest of monoterpenoids mainly thujanes and pinanes. The Costa Rican oil contained 24 monoterpenoids with myrcenone (30,4%), 1,8-cineole (21,4%), myrcene (11,0%), hedycaryol (4,4%) and sabinene (4,3%) as major constituents. Other monoterpenoids were not particularly abundant, with the most prominent members being (Z)-ocimenone (2,3%), limonene (2,0%), α-terpineol (1,9%), piperitone (1,9%), (E)-β-ocimene (1,7%), and (E)-β-ocimenone (1,4%). The regular acyclic monoterpenoids represented 48,5%, the p-menthane monoterpenoids about 28,4% and only 6,1% were thujanes and pinanes.

TABLE 1

Chemical and percentage composition of Lippia alba essential oils from Mexico and Costa Rica

|

Compounda |

RIb |

Lit. RIc |

Class |

Mexico (%)* |

Costa Rica (%)* |

Identification methodd |

|

(E)-Hex-3-enal |

794 |

792 |

A |

t |

|

1;2 |

|

Heptanal |

893 |

901 |

A |

t |

|

1;2;3 |

|

α-Thujene |

926 |

924 |

M |

0,9 |

0,1 |

1;2 |

|

α-Pinene |

936 |

932 |

M |

1,1 |

0,3 |

1;2;3 |

|

Camphene |

949 |

946 |

M |

0,1 |

0,1 |

1;2 |

|

Sabinene |

971 |

969 |

M |

6,8 |

4,3 |

1;2 |

|

β-Pinene |

974 |

974 |

M |

1,0 |

|

1;2;3 |

|

Myrcene |

990 |

988 |

M |

10,9 |

11,0 |

1;2 |

|

p-Cymene |

1 019 |

1 020 |

M |

0,4 |

0,5 |

1;2 |

|

Limonene |

1 024 |

1 024 |

M |

0,5 |

2,0 |

1;2;3 |

|

1,8-Cineole |

1 033 |

1 026 |

OM |

22,3 |

21,4 |

1;2;3 |

|

(E)-β-Ocimene |

1 045 |

1 044 |

M |

0,4 |

1,7 |

1;2 |

|

γ-Terpinene |

1 058 |

1 054 |

M |

0,4 |

|

1;2 |

|

cis-Sabinene hydrate |

1 068 |

1 065 |

OM |

0,5 |

0,4 |

1;2 |

|

Terpinolene |

1 086 |

1 086 |

OM |

0,3 |

|

1;2 |

|

6,7-epoxymyrcene |

1 092 |

1 090 |

OM |

0,3 |

0,3 |

1;2 |

|

Linalool |

1 096 |

1 095 |

OM |

2,0 |

1,4 |

1;2;3 |

|

trans-Sabinene hydrate |

1 098 |

1 098 |

OM |

t |

1;2 |

|

|

α-Campholenal |

1 124 |

1 122 |

OM |

t |

1;2 |

|

|

trans-Pinocarveol |

1 139 |

1 135 |

OM |

t |

1;2 |

|

|

Myrcenone |

1 147 |

1 145 |

OM |

11,2 |

30,4 |

1;2 |

|

(Z)-Tagetone |

1 152 |

1 148 |

OM |

0,5 |

1;2 |

|

|

Isoborneol |

1 158 |

1 155 |

OM |

0,7 |

1;2 |

|

|

Pinocarvone |

1 161 |

1 160 |

OM |

0,3 |

0,3 |

1;2 |

|

δ-Terpineol |

1 164 |

1 162 |

OM |

0,2 |

0,5 |

1;2 |

|

Borneol |

1 168 |

1 165 |

OM |

t |

0,5 |

1;2 |

|

cis-Pinocamphone |

1 172 |

1 172 |

OM |

|

t |

1;2 |

|

Terpinen-4-ol |

1 176 |

1 174 |

OM |

0,3 |

0,2 |

1;2;3 |

|

α-Terpineol |

1 189 |

1 186 |

OM |

0,7 |

1,9 |

1;2;3 |

|

Verbenone |

1 210 |

1 204 |

OM |

0,1 |

|

1;2 |

|

(Z)-Ocimenone |

1 229 |

1 226 |

OM |

7,5 |

2,3 |

1;2 |

|

(E)-Ocimenone |

1 238 |

1 235 |

OM |

10,7 |

1,4 |

1;2 |

|

Piperitone |

1 253 |

1 249 |

OM |

|

1,9 |

1;2 |

|

Bornyl acetate |

1 285 |

1 287 |

OM |

0,2 |

0,1 |

1;2 |

|

Piperitenone |

1 343 |

1 340 |

OM |

|

t |

1;2 |

|

α-Ylangene |

1 375 |

1 373 |

S |

1,6 |

0,5 |

1;2 |

|

β-Bourbonene |

1 383 |

1 387 |

S |

t |

0,1 |

1;2 |

|

β-Cubebene |

1 386 |

1 387 |

S |

0,7 |

0,2 |

1;2 |

|

β-Elemene |

1 388 |

1 389 |

S |

0,7 |

0,4 |

1;2 |

|

Tetradecane |

1 400 |

1 400 |

A |

t |

|

1;2 |

|

β-Caryophyllene |

1 421 |

1 417 |

S |

1,0 |

0,7 |

1;2;3 |

|

β-Copaene |

1 430 |

1 430 |

S |

0,3 |

0,1 |

1;2 |

|

α-Guaiene |

1 435 |

1 437 |

S |

1,8 |

|

1;2 |

|

α-Humulene |

1 453 |

1 452 |

S |

0,8 |

|

1;2;3 |

|

(E)-β-Farnesene |

1 452 |

1 454 |

S |

|

0,4 |

1;2 |

|

allo-Aromadendrene |

1 461 |

1 458 |

S |

0,5 |

0,2 |

1;2 |

|

γ-Muurolene |

1 477 |

1 478 |

S |

0,2 |

0,1 |

1;2 |

|

Germacrene D |

1 484 |

1 484 |

S |

4,1 |

3,2 |

1;2;3 |

|

β-Selinene |

1 489 |

1 489 |

S |

t |

|

1;2 |

|

epi-Cubebol |

1 494 |

1 493 |

OS |

0,2 |

|

1;2 |

|

α-Muurolene |

1 507 |

1 500 |

S |

0,2 |

|

1;2 |

|

α-Bulnesene |

1 509 |

1 509 |

S |

1,7 |

|

1;2 |

|

δ-Amorphene |

1 514 |

1 511 |

S |

|

0,4 |

1;2 |

|

Cubebol |

1 519 |

1 514 |

OS |

0,7 |

|

1;2 |

|

δ-Cadinene |

1 525 |

1 522 |

S |

0,2 |

|

1;2;3 |

|

Hedycaryol |

1 548 |

1 546 |

OS |

|

4,4 |

1;2 |

|

Elemol |

1 549 |

1 548 |

OS |

|

t |

1;2 |

|

Germacrene B |

1 561 |

1 559 |

S |

0,8 |

|

1;2 |

|

(E)-Nerolidol |

1 564 |

1 561 |

OS |

0,2 |

0,2 |

1;2 |

|

Germacrene D-4-ol |

1 570 |

1 574 |

OS |

|

0,4 |

1;2 |

|

Spathulenol |

1 580 |

1 577 |

OS |

0,2 |

|

1;2 |

|

Caryophyllene oxide |

1 590 |

1 582 |

OS |

1,9 |

0,4 |

1;2 |

|

Guaiol |

1 595 |

1 600 |

OS |

|

0,7 |

1;2 |

|

γ-Eudesmol |

1 631 |

1 630 |

OS |

|

0,3 |

1;2 |

|

β-Eudesmol |

1 650 |

1 645 |

OS |

|

0,4 |

1;2 |

|

α-Eudesmol |

1 655 |

1 652 |

OS |

|

0,4 |

1;2 |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Compound class |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Aliphatics (A) |

|

|

|

t |

|

|

|

Monoterpene hydrocarbons (M) |

|

|

|

22,8 |

20,0 |

|

|

Oxygenated monoterpenes (OM) |

|

|

|

57,5 |

63,0 |

|

|

Sesquiterpene hydrocarbons (S) |

|

|

|

14,6 |

6,3 |

|

|

Oxygenated sesquiterpenes (OS) |

|

|

|

3,2 |

7,2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

Total identified |

|

|

|

98,1 |

96,5 |

|

|

Number of compounds |

|

|

|

54 |

43 |

|

aCompounds are listed in order of elution from the poly (5% phenyl-95% dimethylsiloxane) type column.

bRI = Retention index relative to C8-C32 n-alkanes on the same column. cLit. RI= DB-5 (Adams, 2007). dMethod: 1 = Experimental retention index; 2 = MS spectra; 3 = Standard. t: Traces (<0,05%).

*This Journal uses the comma on the line as the decimal marker.

Major and characteristic compounds are in boldface.

Fig. 3. GC-MS chromatogram (TIC) of Mexican Lippia alba essential oil [1. sabinene; 2. myrcene; 3. 1,8-cineole; 4. myrcenone; 5. (Z)-ocimenone; 6. (E)-ocimenone; 7. germacrene D].

Fig. 4. A. GC-MS chromatogram (TIC) of Costa Rican Lippia alba essential oil [1. sabinene; 2. myrcene; 3. 1,8-cineole; 4. myrcenone; 5. (Z)-ocimenone; 6. (E)-ocimenone; 7. germacrene D; 8. hedycaryol; 9. γ-eudesmol; 10. β-eudesmol; 11. α-eudesmol]. B. Blooming strong form (Photography by J. F. Cicció)

DISCUSSION

The two essential oil samples studied could be defined as belonging to the same chemotype. Fischer et al. (2004) proposed the “myrcenone” chemotype and Hennebelle et al. (2006a) the “tagetenone” chemotype (constituted by a mixture of myrcenone and the two isomeric ocimenones) -classified as “chemotype II”. The ketones namely “tagetenone” were identified by Ricciardi et al. (1999) in essential oils of L. alba samples from the Province of Corrientes in northeastern Argentina. In both Mexican and Costa Rican essential oil samples, the 1,8-cineole is present in more than 20% which could explain the medicinal use as an expectorant in communities of both Mexico and Costa Rica. The presence of myrcenone, the two (Z) and (E)-ocimenones, and the addition of 1,8-cineole (more than 20%) suggest that could be established a new subtype of the “tagetenone” chemotype (chemotype II) of L. alba (tagetenone/1,8-cineole subtype).

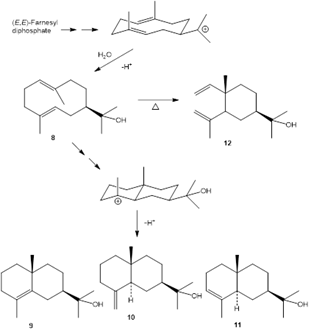

The present study showed that the essential oil of plants growing in Costa Rica contains the sesquiterpenoid hedycaryol (4,4%) (Jones & Sutherland, 1968), which was not found in the specimens studied in Guatemala (Fischer et al., 2004) and Sinaloa, Mexico (Reyes-Solano et al., 2017). Also, hedycaryol is not present in Argentinean (Ricciardi et al., 2009) nor in Mexican oil samples. Additionally, the isomeric sesquiterpene alcohols α-eudesmol (0,4%), β-eudesmol (0,4%), and γ-eudesmol (0,3%) are present only in the Costa Rican samples, probably formed from hedycaryol (via cyclization to a eudesmyl carbocation intermediate) during leaf aging (Cornwell et al., 2000), see Fig. 5. Hedycaryol is a thermally labile and acid-sensitive compound (Wharton et al., 1972) derived from (E,E)-farnesyl diphosphate via cyclization, generating a germacrane carbocation intermediate which is transformed by cyclization to another carbocation of the guaiane skeleton, producing 0,7% of guaiol (and/or isomeric bulnesol) (Sell, 2010) that are present in the Costa Rican essential oils.

Fig. 5. Formation of hedycaryol 8, γ-eudesmol 9, β-eudesmol 10, α-eudesmol 11, and elemol 12. (Cornwell et al., 2000).

The aerial parts of Lippia alba growing in Mexico and Costa Rica produce a terpenoid-rich essential oil whose composition was dominated by myrcenone (11,2-30,4%), 1,8-cineole (21,4-22,3%), myrcene (10,9-11,0%), (E)-ocimenone (1,4-10,7%), (Z)-ocimenone (2,3-7,5%) and sabinene (4,3-6,8%), representing a new ´subtype´ (tagetenone/1,8-cineole) of the chemotype “tagetenone” of this species (Hennebelle et al., 2006a). Additionally, Lippia alba (strong form) from Costa Rica produces an essential oil that differs from all other essential oils of this species studied to date because it contained the isomeric sesquiterpene alcohols hedycaryol, α-eudesmol, β-eudesmol, and γ-eudesmol. Due to this unique composition of sesquiterpenoids in the essential oil of this species, a new subtype of chemotype II can be considered. The existence of the “tagetenone” chemotype of L. alba in Mesoamerica is very interesting. It is naturally distributed from Mexico and Guatemala and is found in the northwestern and central tropical region of Costa Rica, with a great disjunction in the American continent to the Perichón region, Province of Corrientes, in northeast Argentina. This could be the result of an ecological situation developed in the subtropical conditions of Mexico and Guatemala, which displays a subtropical climate similar to that of the Argentine region. Undoubtedly, many more chemical studies of the essential oil composition of Lippia alba populations throughout the American continent are needed to get a better picture of the biogeographic distribution.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors are grateful to the School of Chemistry and the Vice-Rectory of Research (University of Costa Rica) for financial support [Project No. 809-B1-190]. We are grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their invaluable suggestions.

ETHICAL, CONFLICT OF INTEREST AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS

The authors declare that they have fully complied with all pertinent ethical and legal requirements, both during the study and in the production of the manuscript; that there are no conflicts of interest of any kind; that all financial sources are fully and clearly stated in the Acknowledgements section; and that they fully agree with the final edited version of the article. A signed document has been filed in the journal archives.

The declaration of the contribution of each author to the manuscript is as follows:

C. C., F. R. F., and J. F. C.: Data collection, data analysis, bibliographic study, discussion, writing, editing, and review of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

Adams, R. P. (2007). Identification of Essential Oil Components by Gas Chromatography / Mass Spectrometry (4th Ed.). Allured Publishing Corporation.

Amaral, U. do, Ballesteiro, M., Corrêa, P., Alves de Souza, A., & Bajay, M. M. (2017). Polymorphism in Lippia alba clones from the Metropolitan Region of Rio de Janeiro. Journal of Advance in Agriculture, 7(2), 1044-1049. https://doi.org/10.24297/jaa.v7i2.6221

Atkins, S. (2004). Verbenaceae. In J. W. Kadereit (Ed.), The families and genera of flowering plants (Vol. 7, pp. 449-468). Springer-Verlag.

Barbosa, F. G., Lima, M. A. S., & Silveira, E. R. (2005). Total NMR assignments of new [C7-O-C7”]-biflavones from leaves of the limonene-carvone chemotype of Lippia alba (Mill.) N. E. Brown. Magnetic Resonance in Chemistry, 43(4), 334-338. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrc.1546

Barbosa, F. G., Lima, M. A. S., Braz-Filho, R., & Silveira, E. R. (2006). Iridoid and phenylethanoid glycosides from Lippia alba. Biochemical Systematics and Ecology, 34(11), 819-821. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bse.2006.06.006

Cáceres, A. (1996). Plantas de uso medicinal en Guatemala. Editorial Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala.

Cicció, J. F., & Ocampo, R. A. (2004). Aceite esencial de Lippia alba (Verbenaceae) cultivada en el trópico húmedo en el Caribe de Costa Rica. Ingeniería y Ciencia Química, 21(1-2), 13-16.

Cicció, J. F., & Ocampo, R. A. (2006). Variación anual de la composición química del aceite esencial de Lippia alba (Verbenaceae) cultivada en Costa Rica. Lankesteriana, 6(3), 147-152. https://doi.org/10.15517/LANK.V010.7960

Cicció, J. F., & Ocampo, R. (2010). Distribución biogeográfica de Lippia alba (Mill.) N.E. Br. ex Britton & Wilson y quimiotipos en América y el Caribe. In E. Dellacassa (Ed.), Normalización de productos naturales obtenidos de especies de la Flora Aromática Latinoamericana (pp. 107-130). Editora Universitaria da PUCRS.

Cornwell, C. P., Reddy, N., Leach, D. N., & Willie, S. G. (2000). Hydrolysis of hedycaryol: the origin of the eudesmols in the Myrtaceae. Flavour and Fragrance Journal, 15(6), 421-431. https://doi.org/10.1002/1099-1026(200011/12)15:6˂421::AID-FFJ933˃3.0.CO;2-G

Farias M. R., Pértile R., Correa, M. M., de Almeida, M. T. R., Palermo J., & Schenkel, E. P. (2010). Triterpenoid saponins from Lippia alba (Mill.) N. E. Brown. Journal of the Brazilian Chemical Society, 21(5), 927-933. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0103-50532010000500023

Filho, J. G. S., Duringer, J. M., Uchoa, D. E. A., Xavier, H. S., Filho, J. M. B., & Filho, R. B. (2007). Distribution of iridoid glycosides in plants from the genus Lippia (Verbenaceae): An investigation of Lippia alba (Mill.) N. E. Brown. Natural Product Communications, 2(7), 715-716. https://doi.org/10.1177/1934578X0700200701

Fischer, U., López, R., Pöll, E., Vetter, S., Novak, J., & Franz, C. M. (2004). Two chemotypes within Lippia alba populations in Guatemala. Flavour and Fragrance Journal, 19(4),333-335. https://doi.org/10.1002/ffj.1309

Germosén-Robineau, L. (Ed.). (2005). Farmacopea vegetal caribeña. (2nd Ed.). Editorial Universitaria UNAN.

Gilbert, B., Pinto-Ferreira, J. L., & Ferreira-Alves, L. (2005). Monografias de plantas medicinais brasileiras e aclimatadas. Abifito.

Gómez, L. D. (1986). Vegetación de Costa Rica: Vol. 1: Apuntes para una biogeografía costarricense. Editorial Universidad Estatal a Distancia.

Gupta, M. P. (Ed.). (1995). 270 plantas medicinales iberoamericanas. CYTED-SECAB.

Hennebelle, T., Sahpaz, S., Dermont, C., Joseph, H., & Bailleul, F. (2006a). The essential oil of Lippia alba: Analysis of samples from French Overseas Departments and review of previous works. Chemistry and Biodiversity, 3(10), 1116-1125. https://doi.org/10.1002/cbdv.200690113

Hennebelle, T., Sahpaz, S., Joseph, H., & Bailleul, F. (2006b). Phenolics and iridoids of Lippia alba. Natural Product Communications, 1(9), 727-730. https://doi.org/10.1177/1934578X0600100906

Hennebelle, T., Sahpaz, S., Joseph, H., & Bailleul, F. (2008). Ethnopharmacology of Lippia alba. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 116(2), 211-222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2007.11.044

House, P. R., Lagos-Witte, S., Ochoa, L., Torres, C., Mejías, T., & Rivas, M. (1995). Plantas medicinales comunes de Honduras. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Honduras.

Jones, R. V. H., & Sutherland, M. D. (1968). Hedycaryol, the precursor of elemol. Chemical Communications, 1229-1230. https://doi.org/10.1039/C19680001229

Lopes, J. M. L., de Carvalho, H. H., Zorzatto, C., Azevedo, A. L. S., Machado, M. A., Salimena, F. R. G., Grazul, R. M., Gitzendanner, M. A., Soltis, D. E., Soltis, P. S., & Viccini, L. (2020). Genetic relationships and polyploid origins in the Lippia alba complex. American Journal of Botany, 107(3), 466-476. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajb2.1443

Morton, J. F. (1981). Atlas of medicinal plants of Middle America. Bahamas to Yucatan. Charles C Thomas Pub Ltd.

Munir, A. A. (1993). A taxonomic revision of the genus Lippia (Houst. ex.) Linn. (Verbenaceae) in Australia. Journal of the Adelaide Botanic Gardens, 15(2), 129-145. www.jstor.org/stable/23874023

Núñez, E. (1975). Plantas medicinales de Costa Rica y su folklore. Editorial Universidad de Costa Rica.

Polatoğlu, K. (2013). “Chemotypes” -A fact that should not be ignored in natural product studies. The Natural Products Journal, 3(1), 10-14. https://doi.org/10.2174/2210315511303010004

Reis, A. C., Sousa, S. M., Vale, A. A., Pierre, P. M., Franco A. L., Campos, J. M., Vieira, R. F., & Viccini, L. F. (2014). Lippia alba (Verbenaceae): A new tropical autopolyploid complex? American Journal of Botany, 101(6), 1002-1012. https://doi.org/10.3732/ajb.1400149

Reyes-Solano, L., Breksa III, A. P., Valdez-Torres, J. B., Angulo-Escalante, W., & Heredia, J. B. (2017). Chemical composition and antioxidant activity of Lippia alba essential oil obtained by supercritical CO2 and hydrodistillation. African Journal of Biotechnology, 16(17),962-970. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJB2017.15945

Ricciardi, G. A. L., Veglia, J. F., Ricciardi, A. I. A., & Bandoni, A. (1999). Examen comparado de la composición de los aceites esenciales de especies autóctonas de Lippia alba (Mill.) N. E. Br. Universidad Nacional del Nordeste. Comunicaciones científicas y tecnológicas.

Ricciardi, G., Cicció, J. F., Ocampo, R., Lorenzo, D., Ricciardi, A., Bandoni, A., & Dellacassa, E. (2009). Chemical variability of essential oils of Lippia alba (Miller) N. E. Brown growing in Costa Rica and Argentina. Natural Product Communications, 4(6), 853-858. https://doi.org/10.1177/1934578X0900400623

Segleau, J. (2001). Plantas medicinales en el trópico húmedo. Editorial Guayacán.

Sell, C. (2010). Chemistry of essential oils. In K. H. C. Başer & G. Buchbauer (Eds.), Handbook of essential oils: Science, technology and applications. CRC Press, Taylor & Francis.

The Plant List (2013). Verbenaceae. Version 1.1. Published on the Internet. http://www.theplantlist.org/1.1/browse/A/Verbenaceae/

Timóteo, P., Karioti, A., Leitao, S. G., Vincieri, F. F., & Bilia, A. R. (2008). HPLC/DAD/ESI-MS análisis of non-volatile constituents of three Brazilian chemotypes of Lippia alba (Mill.) N. E. Brown. Natural Product Communications, 3(12), 2017-2020.

Topographic Map of Costa Rica. Sandalmelik. (2007, September 16). Costa Rica Topography.png. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/file:Costa_Rica_Topography.png

van Den Dool, H., & Kratz, P. D. (1963). A generalization of the retention index system including linear temperature programmed gas-liquid partition chromatography. Journal of Chromatography A, 11, 463-471. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0021-9673(01)80947-X

von Poser, G. L., Toffoli, M. E., Sobral, M., & Henriques, A. T. (1997). Iridoid glucosides substitution patterns in Verbenaceae and their taxonomic implication. Plant Systematics and Evolution, 205, 265-268. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01464409

Wharton, P. S., Sundin, C. E., Johnson, D. W., & Kluender, H. C. (1972). Synthesis of dl-hedycaryol. Journal of Organic Chemistry, 37(1), 34-38. https://doi.org/10.1021/jo00966a009