Chemical composition of essential oils of the tree Melaleuca quinquenervia (Myrtaceae) cultivated in Costa Rica

Carlos

Chaverri1![]() & José F. Cicció1

& José F. Cicció1![]()

1. Escuela de Química, Universidad de Costa Rica. San José, 11501-2060 Costa Rica and Centro de Investigaciones en Productos Naturales (CIPRONA), Universidad de Costa Rica. San José, 11501-2060 Costa Rica; cachaverri@gmail.com, jfciccio@gmail.com

Received 18-XI-2020 Corrected 18-XII-2020 Accepted 06-II-2021

DOI: https://doi.org/10.22458/urj.v13i1.3327

|

ABSTRACT. Introduction: Melaleuca is a Myrtaceous genus of flowering plants of about 290 species, distributed throughout Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, Australia, and New Caledonia. Objective: To identify the chemical composition of the essential oils from leaves, twigs and fruits of M. quinquenervia cultivated as ornamental in Costa Rica. Methods: The essential oils were obtained through the steam distillation process in a Clevenger type apparatus. The chemical composition of the oils was done by GC-FID and GC-MS, using the retention indices on a DB-5 type capillary column in addition to mass spectral fragmentation patterns. Results: The essential oils consisted mainly of terpenoids (88,2-96,6%). A total of 88 compounds were identified, accounting for 93.1-97.0% of the total amount of the oils. The major constituents from the leaf oil were 1,8-cineole (31,5%), viridiflorol (21,7%), and α-pinene (17,9%). The fruit essential oil consisted mainly of viridiflorol (42,1%), α-pinene (15,0%), limonene (6,4%), α-humulene (4,7%), β-caryophyllene (3,9%), and 1,8-cineole (3,4%). The major components of twigs oil were viridiflorol (66,0%), and 1,10-di-epi-cubenol (4,0%). Conclusion: The plants introduced in Costa Rica belong to chemotype II whose oils contain as major constituents 1,8-cineole and viridiflorol, and it suggest that the original plants were brought from southern Queensland or northern New South Wales (Australia) or from New Caledonia.

Keywords: Melaleuca quinquenervia, essential oils, 1,8-cineole, viridiflorol, α-pinene.

|

RESUMEN. “Composición química de los aceites esenciales del árbol Melaleuca quinquenervia (Myrtaceae) cultivado en Costa Rica.” Introducción: Melaleuca (Myrtaceae) consta de 290 especies, distribuidas principalmente en Indonesia, Papúa Nueva Guinea, Australia y Nueva Caledonia. Objetivo: Identificar la composición química de los aceites esenciales en hojas, tallos y frutos de M. quinquenervia, cultivado en Costa Rica como árbol ornamental. Métodos: La extracción del aceite se efectuó mediante el procedimiento de hidrodestilación, usando un equipo de Clevenger modificado. La composición química de los aceites se analizó mediante técnicas de GC-FID y de GC-MS, se calcularon los índices de retención (columna capilar tipo DB-5) y se obtuvieron los espectros de masas de cada constituyente. Resultados: Los aceites esenciales están constituidos principalmente por terpenoides (88,2-96,6%). Se identificaron en total 88 compuestos, correspondientes a un 93,1-97,0% de los constituyentes totales. Los componentes mayoritarios del aceite de las hojas fueron 1,8-cineol (31,5%), viridiflorol (21,7%) y α-pineno (17,9%). Los aceites de los frutos contienen principalmente viridiflorol (42,1%), α-pineno (15,0%), limoneno (6,4%), α-humuleno (4,7%), β-cariofileno (3,9%) y 1,8-cineol (3,4%). Los constituyentes mayoritarios de los aceites de las ramitas fueron viridiflorol (66,0%) y 1,10-di-epi-cubenol (4,0%). Conclusión: Las plantas introducidas en Costa Rica pertenecen al quimiotipo II, cuyos aceites contienen como componentes principales 1,8-cineol y viridiflorol; esto sugiere que las plantas originales provienen de la región sur de Queensland o del norte de Nueva Gales del Sur (Australia) o de Nueva Caledonia.

Palabras clave: Melaleuca quinquenervia, aceites esenciales, 1,8-cineol, viridiflorol, α-pineno.

|

Myrtaceae (the myrtle family) is the ninth largest flowering plant family on Earth with about 132 genera and ca. 5 950 species with a wide distribution in tropical and subtropical climates of the world, mainly concentrated in the Southern Hemisphere, largely composed of small trees and shrubby species (Christenhusz & Byng, 2016; Govaerts et al., 2008). This family of plants has important economic value. Some species of the genus Eucalyptus produce a hardwood timber that is used for electrical transmission poles to make temporary construction and it is used in pulp and paper industries. Several species are important in horticulture as ornamentals and as a source of medicinally important essential oils containing cineole (eucalyptol) or citral (geranial + neral) used as expectorants and to relieve a cough. Melaleuca alternifolia Cheel is notable for its anti-fungal and antibiotic oil (tea tree oil) used safely in multiple topical products. Of great importance is the clove oil from the dried flower buds of Syzygium aromaticum (L.) Merr. & L. M. Perry (valuable as commercial spice) and Pimenta racemosa (Mill.) J. W. Moore (bay oil) which is used by the perfume industry. Although this family is not an important source of food, edible fruits are produced by species of some genera: Psidium guajava L. (guava), P. friedrichsthalianum (O. Berg) Nied. (cas), Acca sellowiana (O. Berg) Burret (feijoa), Eugenia uniflora L. (pitanga), and Syzygium spp. (roseapples). These fruits are eaten raw or cooked and are used for making beverages, jellies, jams, and preserves.

Melaleuca L. is a genus of shrubs and trees included in the tribe Melaleuceae, composed by 290 species with 37 infraspecific taxa (Brophy, Craven & Doran, 2013), with the majority of species endemic to Australia and a few occurring in Malaysia, Indonesia, New Guinea, the Solomon Islands, and New Caledonia. The evergreen tree Melaleuca quinquenervia (Cav.) S. T. Blake, commonly called “niaouli” (New Caledonia) and “paperbark tea tree” (because the whitish outer bark peels into thin layers) with simple grayish green alternate leaves, is native from Queensland, New South Wales, Indonesia, Papua New Guinea and is widespread in New Caledonia. When the leaves are crushed, they give off a scent with a camphoraceous aroma. The spicate inflorescences are white or creamy-white shaped like bottle brushes. The fruits are woody, small cylindrical capsules, borne in clusters on twigs.

Early works on the phytochemistry of M. quinquenervia revealed the presence of the flavonoids strobopinin, cryptostrobin and melanervin from flower extracts (Wagner, Seligmann, Hörhammer, Chari, & Morton, 1976; Seligmann & Wagner, 1981) and ursolic acid as leaf wax constituent (Courtney, Lassak, & Speirs, 1983). From the leaves of M. quinquenervia, El-Toumy, Marzouk, Moharram and Aboutabl (2001) determined a new flavonoid 5,7,3',4'-tetrahydroxyflavone 2'-O-3-D-glucopyranuronide and eight known flavonol glycosides. Aboutabl, Soliman and Moharram (1999) isolated a novel cyclohexanoid monoterpene glucoside named melacoside A. Lee, Wang, Lee, Kuo and Chou (2002) isolated two new and four known glycosides, some of them with vasorelaxation activity in rats. Also, from leaves, Moharram, Marzouk, El-Toumy, Ahmed and Aboutabl (2003) isolated four polyphenolic acid derivatives and three ellagitannins. The major compound isolated was grandinin, showing radical scavenging activity and exhibiting hypoglycemic effect in mice.

The chemical composition of leaf essential oil from these species has been the subject of several studies (Aboutabl, Tohamy, De Poter, & De Buyck, 1991; Ramanoelina, Bianchini, Andriantsiferana, Viano, & Gaydou, 1992; Ramanoelina, Viano, Bianchini, & Gaydou, 1994; Moudachirou et al., 1996; Philippe, Goeb, Suvarnalatha, Sankar, & Suresh, 2002; Ireland, Hibbert, Goldsack, Doran, & Brophy, 2002; Trilles et al., 2006; Wheeler, Pratt, Giblin-Davis, & Ordung, 2007; Silva, Barbosa, Maltha, Pinheiro, & Ismail, 2007; Gbenou, Moudachirou, Chalchat, & Figuérédo, 2007; Morales-Rico, Marrero-Delange, González-Canavaciolo, Quintana-Ramos, & González-Camejo, 2012; Morales-Rico et al., 2015; Siddique, Mazhar, Firdaus-E-Bareen, & Parveen, 2018; Acha et al., 2019; Diallo et al., 2020). The niaouli essential oil has been produced since the last decade of the 17th century in the northern region of New Caledonia, and at present it is produced commercially in Madagascar. The oil is used in aromatherapy, as antiseptic and expectorant for respiratory ailments, and in pharmaceutical preparations to the relief of coughs and colds. It is indicated mainly for rhinitis, sinusitis and bronchitis (Vanaclocha & Cañigueral, 2003). In Costa Rica, the leaf infusion is taken as a sudorific, antispasmodic and pulmonary antiseptic (Morton, 1981). To the best of our knowledge, the chemical composition of the oils of M. quinquenervia cultivated as ornamental in Costa Rica has not been described previously.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant materials: Different morphological parts of Melaleuca quinquenervia were collected from a single tree (leaves, 1,80 kg, fruits, 0,65 kg and twigs, 0,47 kg), in the locality of Mercedes de Montes de Oca (Calle Masís), Province of San José, Costa Rica (9°56’20.50’’ N, 84°03’06.50” W, at an elevation of 1 207m) in January, 2017. A voucher specimen was deposited in the Herbarium of the University of Costa Rica (USJ 111056).

Isolation of the essential oils: Oils were obtained by hydrodistillation at atmospheric pressure, for three hours using a Clevenger-type apparatus. The distilled oils were collected and dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate, filtered and stored between 0°C and 10°C in the dark, until further analysis. The essential oil yields (v/w) from diverse morphological parts were: 1,20 % (leaf), 0,33 % (fruit), and 0,06 % (twig).

Gas chromatography (GC-FID): The essential oils of M. quinquenervia were analyzed by gas chromatography with flame ionization detector (GC-FID) using a Shimadzu GC-2014 gas chromatograph. The data obtained was on a 5% diphenyl-/95% dimethylpolysiloxane fused silica capillary column (30m x 0,25mm; film thickness 0,25μm), (MDN-5S, Supelco). The GC integrations were performed with a LabSolutions, Shimadzu GC Solution, Chromatography Data System, software version 2.3. The operating conditions used were: carrier gas N2, flow 1,0mL/min; oven temperature program: (60 to 280) °C at 3 °C/min, 280 °C (2 min); sample injection port temperature 250 °C; detector temperature 280 °C; split 1:60.

Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS): The analyses by gas chromatography coupled to mass selective detector (GC-MS) were carried out using a Shimadzu GC-17A gas chromatograph coupled with a GCMS-QP5000 apparatus and CLASS 5000 software with Wiley 139 and NIST computerized databases. The data obtained was on a 5% phenyl-/95% dimethylpolysiloxane fused silica capillary column (30m x 0,25mm; film thickness 0,25μm), (MDN-5S, Supelco). The operating conditions used were: carrier gas He, flow 1,0mL/min; oven temperature program: (60 to 280) °C at 3 °C/min; sample injection port temperature 250 °C; detector temperature 260 °C; ionization voltage: 70eV; ionization current 60μA; scanning speed 0,5 s over 38 to 400 amu range; split 1:70.

Compound identification: Identification of the oil components were performed using the retention indices which were calculated in relation to a homologous series of n-alkanes, on a 5% phenyl-/95% dimethylpolysiloxane type column (van Den Dool & Kratz, 1963), and by comparison of their mass spectra with those published in the literature (Stenhagen, Abrahamsson, & MacLafferty, 1974; Swigar & Silverstein, 1981; Adams, 2007) and those of our own database, or comparing their mass spectra with those available in the computerized databases (NIST107 and Wiley139) or in a web source (Wallace, 2019). To obtain the retention indices for each peak, 0,1μL of n-alkane mixture (Sigma, C8-C32 standard mixture) was injected under the same experimental conditions reported above. Integration of the total chromatogram (GC-FID) expressed as area percent without correction factors, has been used to obtain quantitative compositional data.

RESULTS

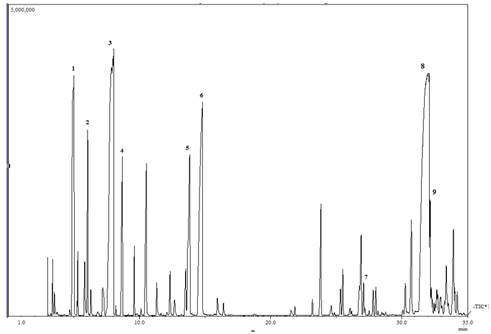

The chemical composition of the leaf, fruit and twig oils of M. quinquenervia cultivated in Costa Rica is summarized in Table 1. These oils consisted largely of terpenoids (88,2-96,6%) with minor amount of aliphatics and benzenoids (ca. 0,5%). The major constituents of the leaf oil were 1,8-cineole (31,5%), viridiflorol (21,7%), α-pinene (17,9%), α-terpineol (6,5%), terpinen-4-ol (2,6%), γ-terpinene (2,3%), β-pinene (1,9%), and ledol (1,3%), see the total ion chromatogram (TIC) in Fig. 1. The composition of fruit essential oil was dominated by viridiflorol (42,1%), α-pinene (15,0%), limonene (6,4%), α-humulene (4,7%), β-caryophyllene (3,9%), 1,8-cineole (3,4%) and α-terpineol (2,0%). The twig essential oil was constituted mainly by viridiflorol (66,0%) accompanied by lesser amounts of 1,10-di-epi-cubenol (4,0%), intermedeol (2,8%), caryophyllene oxide (2,7%), trans-β-guaiene (2,6%), α-eudesmol (2,3%), and γ-eudesmol (2,1%).

TABLE 1

Chemical composition of the essential oils from Melaleuca quinquenervia cultivated in Costa Rica.

|

Compounda |

RIb |

Lit. RIc |

Class |

Leaves (%) |

Fruits (%) |

Twigs (%) |

Identification methodd |

|

(E)-Hex-2-enal |

840 |

846 |

A |

0,3 |

- |

- |

1;2 |

|

(Z)-Salvene |

845 |

847 |

M |

- |

t |

- |

1;2 |

|

(Z)-Hex-3-en-1-ol |

851 |

850 |

A |

0,2 |

- |

- |

1;2 |

|

Hexan-1-ol |

865 |

863 |

A |

t |

t |

t |

1;2;3 |

|

Heptanal |

900 |

901 |

A |

- |

- |

t |

1;2 |

|

α-Thujene |

927 |

924 |

M |

0,1 |

- |

- |

1,2 |

|

α-Pinene |

934 |

932 |

M |

17,9 |

15,0 |

1,9 |

1;2;3 |

|

α-Fenchene |

944 |

945 |

M |

t |

T |

- |

1;2 |

|

Camphene |

948 |

946 |

M |

0,4 |

0,3 |

0,1 |

1;2 |

|

Benzaldehyde |

959 |

952 |

B |

- |

0,4 |

0,1 |

1;2;3 |

|

Sabinene |

965 |

969 |

M |

0,7 |

t |

- |

1;2 |

|

β-Pinene |

978 |

974 |

M |

1,9 |

- |

0,2 |

1;2;3 |

|

2-Pentylfuran |

985 |

984 |

Misc |

- |

- |

0,1 |

1;2 |

|

Myrcene |

987 |

988 |

M |

0,2 |

0,3 |

- |

1;2 |

|

δ-2-Carene |

1 006 |

1 001 |

M |

- |

0,2 |

- |

1;2 |

|

α-Phellandrene |

1 107 |

1 002 |

M |

0,1 |

- |

- |

1;2 |

|

α-Terpinene |

1 018 |

1 014 |

M |

0,6 |

- |

t |

1;2 |

|

p-Cymene |

1 020 |

1 020 |

M |

t |

- |

- |

1;2 |

|

o-Cymene |

1 025 |

1 022 |

M |

- |

0,2 |

0,1 |

1;2 |

|

Limonene |

1 027 |

1 024 |

M |

0,9 |

6,4 |

1,5 |

1;2;3 |

|

1,8-Cineole |

1 029 |

1 026 |

OM |

31,5 |

3,4 |

0,7 |

1;2;3 |

|

(Z)-β-Ocimene |

1 036 |

1 032 |

M |

t |

t |

- |

1;2 |

|

(E)-β-Ocimene |

1 047 |

1 044 |

M |

- |

0,2 |

0,1 |

1;2 |

|

γ-Terpinene |

1 058 |

1 054 |

M |

2,3 |

0,4 |

0,1 |

1;2 |

|

Octan-1-ol |

1 069 |

1 065 |

A |

- |

- |

0,1 |

1;2;3 |

|

trans-Linalol oxide (furanoid) |

1 086 |

1 084 |

OM |

- |

- |

- |

1;2 |

|

Terpinolene |

1 089 |

1 086 |

M |

0,6 |

0,4 |

0,1 |

1;2 |

|

Methyl benzoate |

1 095 |

1 088 |

B |

- |

0,2 |

- |

1;2 |

|

Linalool |

1 100 |

1 095 |

OM |

- |

- |

0,2 |

1;2;3 |

|

exo-Fenchol |

1 115 |

1 118 |

OM |

- |

0,2 |

0,1 |

1;2 |

|

neo-Isopulegol |

1 146 |

1 144 |

OM |

- |

0,1 |

- |

1;2 |

|

Camphene hydrate |

1 150 |

1 145 |

OM |

- |

0,1 |

- |

1;2 |

|

cis-Dihydro-α-terpineol |

1 161 |

1 160 |

OM |

- |

0,1 |

- |

1:2 |

|

Borneol |

1 166 |

1 165 |

OM |

- |

0,4 |

- |

1;2 |

|

(E)-Non-2-enal |

1 167 |

1 166e |

A |

- |

- |

0,1 |

1;2 |

|

Terpinen-4-ol |

1 178 |

1 174 |

OM |

2,6 |

0,6 |

0,1 |

1;2;3 |

|

cis-Pinocarveol |

1 180 |

1 182 |

OM |

- |

t |

- |

1;2 |

|

Methyl salicylate |

1 188 |

1 190 |

B |

- |

t |

- |

1;2 |

|

α-Terpineol |

1 192 |

1 192f |

OM |

6,5 |

2,0 |

0,4 |

1;2;3 |

|

Decanal |

1 206 |

1 201 |

A |

- |

- |

0,1 |

1;2 |

|

Citronellol |

1 219 |

1 223 |

OM |

0,1 |

t |

- |

1;2 |

|

Carvacrol, methyl ether |

1 244 |

1 241 |

OM |

- |

0,1 |

- |

1;2 |

|

Benzyl acetone |

1 247 |

1 245g |

B |

0,1 |

- |

- |

1;2 |

|

Eugenol |

1 358 |

1 356 |

PP |

0,1 |

- |

- |

1;2;3 |

|

Isoledene |

1 375 |

1 374 |

S |

t |

- |

- |

1;2 |

|

α-Copaene |

1 379 |

1 374 |

S |

- |

0,2 |

0,1 |

1;2 |

|

α-Gurjunene |

1 413 |

1 409 |

S |

0,1 |

0,6 |

0,2 |

1;2 |

|

(E)-Caryophyllene (β-Caryophyllene) |

1 419 |

1 417 |

S |

0,9 |

3,9 |

1,2 |

1;2;3 |

|

Aromadendrene |

1 438 |

1 439 |

S |

- |

0,1 |

0,2 |

1;2 |

|

α-Humulene |

1 458 |

1 452 |

S |

0,2 |

0,7 |

0,3 |

1;2;3 |

|

allo-Aromadendrene |

1 460 |

1 458 |

S |

0,3 |

- |

- |

1;2 |

|

Dehydroaromadendrene |

1 464 |

1 460 |

S |

- |

- |

0,6 |

1;2 |

|

9-epi-(E)-Caryophyllene |

1 465 |

1 464 |

S |

- |

1,1 |

0,1 |

1;2 |

|

4,5-di-epi-Aristolene |

1 474 |

1 471 |

S |

- |

t |

- |

1;2 |

|

γ-Gurjunene |

1 478 |

1 475 |

S |

- |

0,2 |

0,1 |

1;2 |

|

Germacrene D |

1 489 |

1 484 |

S |

- |

- |

0,1 |

1;2 |

|

β-Selinene |

1 490 |

1 489 |

S |

- |

- |

0,3 |

1;2 |

|

cis-β-Guaiene |

1 491 |

1 493 |

S |

- |

0,7 |

- |

1;2 |

|

γ-Amorphene |

1 492 |

1 495 |

S |

0,2 |

- |

- |

1;2 |

|

Viridiflorene |

1 494 |

1 496 |

S |

- |

- |

0,3 |

1;2 |

|

α-Selinene |

1 494 |

1 498 |

S |

0,1 |

0,4 |

- |

1;2 |

|

α-Muurolene |

1 501 |

1 500 |

S |

0,8 |

4,7 |

- |

1;2 |

|

trans-β-Guaiene |

1 502 |

1 502 |

S |

- |

- |

2,6 |

1;2 |

|

(E,E)-α-Farnesene |

1 505 |

1 505 |

S |

t |

0,1 |

- |

1;2 |

|

γ-Cadinene |

1 519 |

1 513 |

S |

0,2 |

0,7 |

0,4 |

1;2 |

|

δ-Cadinene |

1 528 |

1 522 |

S |

0,2 |

1,1 |

0,5 |

1;2 |

|

cis-Calamenene |

1 529 |

1 528 |

S |

- |

- |

0,1 |

1;2 |

|

trans-Cadina-1,4-diene |

1 530 |

1 533 |

S |

t |

0,1 |

- |

1;2 |

|

α-Cadinene |

1 541 |

1 537 |

S |

t |

0,1 |

0,1 |

1;2 |

|

Palustrol |

1 570 |

1 567 |

OS |

0,3 |

0,5 |

0,6 |

1;2 |

|

Caryophyllene oxide |

1 589 |

1 582 |

OS |

0,8 |

- |

2,7 |

1;2 |

|

Viridiflorol |

1 598 |

1 592 |

OS |

21,7 |

42,1 |

66,0 |

1;2 |

|

Ledol |

1 601 |

1 602 |

OS |

1,3 |

- |

T |

1;2 |

|

5-epi-7-epi-α-Eudesmol |

1 604 |

1 607 |

OS |

- |

- |

T |

1;2 |

|

1,10-di-epi-Cubenol |

1 614 |

1 618 |

OS |

- |

- |

4,0 |

1;2 |

|

1-epi-Cubenol |

1 631 |

1 627 |

OS |

t |

0,2 |

- |

1;2 |

|

Eremoligenol |

1 628 |

1 629 |

OS |

0,2 |

t |

0,3 |

1;2 |

|

γ-Eudesmol |

1 637 |

1 630 |

OS |

t |

- |

2,1 |

1;2 |

|

epi-α-Cadinol |

1 638 |

1 638 |

OS |

0,4 |

- |

- |

1;2 |

|

epoxy-allo-Aromadendrene |

1 640 |

1 639 |

OS |

- |

- |

0,4 |

1;2 |

|

epi-α-Muurolol |

1 640 |

1 640 |

OS |

t |

- |

- |

1;2 |

|

Cubenol |

1 641 |

1 645 |

OS |

- |

- |

1,3 |

1;2 |

|

Agarospirol |

1 642 |

1 646 |

OS |

- |

1,3 |

- |

1;2 |

|

α-Eudesmol |

1 658 |

1 652 |

OS |

0,5 |

1,4 |

2,3 |

1;2 |

|

Intermedeol |

1 663 |

1 665 |

OS |

t |

t |

2,8 |

1;2 |

|

Bulnesol |

1 672 |

1 670 |

OS |

0,1 |

1,8 |

0,9 |

1;2 |

|

β-Bisabolol |

1 677 |

1 674 |

OS |

- |

- |

0,2 |

1;2 |

|

(2Z,6E)-Farnesol |

1 724 |

1 722 |

OS |

t |

0,1 |

0,1 |

1;2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Compound class |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Aliphatics (A) |

|

|

|

0,5 |

- |

0,3 |

|

|

Monoterpene hydrocarbons (M) |

|

|

|

25,7 |

23,4 |

4,1 |

|

|

Oxygenated monoterpenes (OM) |

|

|

|

40,7 |

7,0 |

1,5 |

|

|

Sesquiterpene hydrocarbons (S) |

|

|

|

3,0 |

14,7 |

7,6 |

|

|

Oxygenated sesquiterpenes (OS) |

|

|

|

25,3 |

47,4 |

83,8 |

|

|

Phenyl propanoids (PP) |

|

|

|

0,1 |

- |

- |

|

|

Benzenoids (B) |

|

|

|

0,1 |

0,6 |

0,1 |

|

|

Miscelaneous (Misc) |

|

|

|

- |

- |

0,1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Identified components (%) |

|

|

|

95,4 |

93,1 |

97,0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

aCompounds listed in order of elution from 5% phenyl-95% dimethylpolysiloxane type column.

bRI = Retention index on the same column in reference to C8-C32 n-alkanes. cLit. RI = J&W, DB-5 (Adams, 2007). dMethod: 1 = Experimental retention index; 2 = MS spectra; 3 = Standard. e(Pino, Marbot, & Vázquez, 2004). f(Zoghbi, Andrade, Santos, Silva, & Maia, 1998). g(Collin & Gagnon, 2016).

t = Traces (<0,05%).

The essential oil of M. quinquenervia is principally produced in the leaves (1,20%), while in the fruits, the amount is about three times less (0,33%), and the yield of the twigs is very low (0,06 %). The oils are composed primarily by terpenoids. The main components of the leaf oil were cyclic monoterpenoids (66,4%) and sesquiterpenoids (28,3%). In the oil of the fruits, the proportions of both types of terpenoids are reversed with respect to that of the leaf oil: 30,4% and 62,1% respectively. The twig oil contained large amounts of sesquiterpenoids (>90%) with a high percentage of viridiflorol (66,0%).

Fig. 1. GC-MS chromatogram (TIC) of M. quinquenervia leaf oil (1. α-pinene; 2. β-pinene, 3. 1,8-cineole; 4. γ-terpinene; 5. terpinen-4-ol; 6. α-terpineol; 7. α-muurolene; 8. viridiflorol; 9. ledol).

DISCUSSION

The essential oil from leaves of M. quinquenervia collected near Toamasina, Madagascar, revealed the presence of four chemotypes (Ramanoelina et al., 1994). Moudachirou et al. (1996) described three “chemovarieties” from Benin. Trilles, Bouraïma-Madjebi and Valet (1999) revealed the existence of five chemotypes in New Caledonia. Ireland et al. (2002) studied the chemical variation in the leaf oil over the geographical range of Australia and Papua New Guinea, reporting two major chemotypes. Trilles et al. (2006) classified the niaouli oils from New Caledonia into three chemotypes, using principal component analysis. Wheeler (2006) reported the existence of two chemotypes in Florida. Gbenou et al. (2007) reported the presence of three chemotypes in Benin. Despite the fact that there are reported about six chemotypes of this species, according to the criteria of Brophy et al. (2013), there are two distinct chemotypes of M. quinquenervia; chemotype I produce leaf oils rich in (E)-nerolidol (in amounts up to 95%) and chemotype II give rice to oils rich in 1,8-cineole (and/or) viridiflorol as well as lesser amounts of other terpenes and terpenoids.

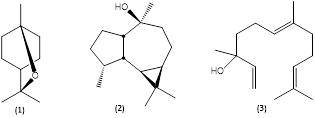

The leaf oil produced from M. quinquenervia cultivated in Costa Rica contained as major constituents 1,8-cineole (1) (31,5%) (see numbered chemical structures in Fig. 2) and viridiflorol (2) (21,7%), as well as lesser amounts of α-pinene (17,9%), α-terpineol (6,5%), terpinen-4-ol (2,6%), γ-terpinene (2,3%), β-pinene (1,9%), ledol (1,3%), β-caryophyllene (0,9%), and caryophyllene oxide (0,8%), corresponding to chemotype II, with a natural occurrence in Queensland, New South Wales from Cape York Peninsula southwards along the coastal and subcoastal regions to the Sydney district, Australia. Also occurs in southern Papua province, Indonesia (characterized also by the presence of globulol) and is widespread in New Caledonia. Typically, chemotype II contains the cyclic terpenoids 1,8-cineole (10-75%), viridiflorol (13-66%), α-terpineol (0,5-14%), and β-caryophyllene (0,5-28%) (Ireland et al., 2002). According to Padovan, Keszei, Köllner, Degenhardt, and Foley (2010), the viridiflorol biosynthesis occurs by the catalytic action of terpene synthase enzymes, and the genes coding for these enzymes are present in the genome of the species, regardless of the chemotype, but are expressed only in the viridiflorol chemotype. The acyclic (E)-nerolidol (3) (see Fig. 2) is the main terpenoid in the chemotype I leaf oil and was undetectable in the Costa Rican essential oil samples.

Fig. 2. Terpenoids from Melaleuca quinquenervia leaf oil. (1) 1,8-Cineole; (2) viridiflorol; (3) (E)-nerolidol.

Qualitative and quantitative differences of the leaf, fruit and twig essential oil compositions were observed. A considerable increase in the proportion of viridiflorol is noted according to the morphological part from which the oil is obtained. Thus, the amount of viridiflorol in the leaves (21,7%) is lower and increases in the oils of the fruits (42,1%) and twigs (66,0%). On the other hand, the proportion of 1,8-cineole varies inversely from leaves (31,5%) to fruits (3,4%), and twigs (0,7%).

The experimental fact that foliar essential oil of M. quinquenervia growing in Costa Rica produces as major constituents 1,8-cineole (31,5%) and viridiflorol (21,7%), it seems to indicate that the plants introduced in Costa Rica belong to chemotype II, as defined by Ireland et al. (2002) and Brophy et al. (2013), and it could suggest that the original plants were brought from Australia (coming from southern Queensland or northern New South Wales) or New Caledonia.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to express our gratitude to the School of Chemistry and Vice-Rectory of Research (University of Costa Rica) for financial support [Project number 809-B9-170] and to C. O. Morales (School of Biology, University of Costa Rica) for his help in identifying plant material.

ETHICAL, CONFLICT OF INTEREST AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS

The authors declare that they have fully complied with all pertinent ethical and legal requirements, both during the study and in the production of the manuscript; that there are no conflicts of interest of any kind; that all financial sources are fully and clearly stated in the acknowledgements section; and that they fully agree with the final edited version of the article. A signed document has been filed in the journal archives.

The declaration of the contribution of each author to the manuscript is as follows:

C. C. and J. F. C.: Data collection, data analysis, bibliographic study, discussion, writing, editing and review of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

Aboutabl, E. A., El Tohamy, S. F., De Poter, H. L., & De Buyck, L. F. (1991). A comparative study of the essential oils from three Melaleuca species growing in Egypt. Flavour and Fragrance Journal, 6(2), 139-141. DOI: 10.1002/ffj.2730060209

Aboutabl, E. A., Soliman, H. S. M., & Moharram, F. A. (1999). Melacoside A, a novel monoterpene glucoside from Melaleuca quinquenervia (Cav.) S.T. Blake. Al-Azhar Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, 23, 110-115.

Acha, E., Aïkpe, J. F. A., Adoverlande, J., Assogba, M. F., Agossou, G., Sezan, A., Dansou, H. P., & Gbenou, J. D. (2019). Anti-inflammatory properties of Melaleuca quinquenervia (Cav.) S. T. Blake Myrtaceae (Niaouli) leaves’ essential oil. Journal of Chemical and Pharmaceutical Research, 11(1), 36-50. Retrieved from https://www.jocpr.com/articles/antiinflammatory-properties-of-melaleuca-quinquenervia-cav-st-blake-myrtaceae-niaouli-leaves-essential-oil.pdf

Adams, R. P. (2007). Identification of Essential Oil Components by Gas Chromatography/ Quadrupole Mass Spectroscopy. Carol Stream, Illinois, USA: Allured Publishing Corporation.

Brophy, J. J., Craven, L. A., & Doran, J. C. (2013). Melaleucas: Their botany, essential oils and uses, ACIAR Monograph No. 156. Canberra, Australia: Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research.

Christenhusz, M. J. M., & Byng, J. W. (2016). The number of known plants species in the world and its annual increase. Phytotaxa, 261(3), 201-217. DOI: 10.11646/phytotaxa.261.3.1

Collin, G., & Gagnon, H. (2016). Chemical composition and stability of the hydrosol obtained during the production of essential oils. III. The case of Myrica gale L., Comptonia peregrina (L.) Coulter and Ledum groenlandicum Retzius. American Journal of Essential Oils and Natural Products, 4(1), 07-19. Retrieved from https://www.essencejournal.com/archives/2016/4/1/A

Courtney, J. L., Lassak, E. V., & Speirs, G. B. (1983). Leaf wax constituents of some myrtaceous species. Phytochemistry, 22(4), 947-949. DOI:10.1016/0031-9422(83)85027-4

Diallo, A., Tine, Y., Diop, A., Ndoye, I., Traoré, F., Boye, C. S. B., Costa, J., Paoline, J., & Wélé, A. (2020). Chemical composition and antibacterial activity of essential oil of Melaleuca quinquenervia (Cav.) S. T. Blake (Myrtaceae). Asian Journal of Applied Chemistry Research, 5(2), 46-52. DOI: 10.9734/AJACR/2020/v5i230132

El-Toumy, S. A. A., Marzouk, M. S., Moharram, F. A., & Aboutabl, E. A. (2001). Flavonoids of Melaleuca quinquenervia. Pharmazie, 56(1), 94-95. DOI: 10.1002/chin.200117207

Gbenou, J. D., Moudachirou, M., J.-C., Chalchat, & Figuérédo, G. (2007). Chemotypes in Melaleuca quinquenervia (Cav.) S. T. Blake (Niaouli) from Benin using multivariate statistical analysis of their essential oils. Journal of Essential Oil Research, 19(2), 101-104. DOI: 10.1080/10412905.2007.9699239

Govaerts, R., Sobral, M., Ashton, P., Barrie, F., Holst, B. K., Landrum, L. L., Matsumoto, K., Mazine, F. F., Lughadha, E. N., Proneça, C., Soares-Silva, L. H., Wilson, P. G., & Lucas, E. (2008). World Checklist of Myrtaceae. Richmond, United Kingdom: Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew.

Ireland, B. F., Hibbert, D. B., Goldsack, R. J., Doran, J. C., & Brophy, J. J. (2002). Chemical variation in the leaf essential oil of Melaleuca quinquenervia (Cav.) S. T. Blake. Biochemical Systematics and Ecology, 30(5), 457-470. DOI: 10.1016/S0305-1978(01)00112-0

Lee, T. H., Wang, G. J., Lee, C. K., Kuo, Y. H., & Chou, C. H. (2002). Inhibitory effects of glycosides from the leaves of Melaleuca quinquenervia on vascular contraction of rats. Planta Medica, 68(6), 492-496. DOI: 10.1055/s-2002-32563

Moharram, F. A.; Marzouk, M. S.; El-Toumy, S. A. A.; Ahmed, A. A. E.; Aboutabl, E. A. (2003). Polyphenols of Melaleuca quinquenervia leaves - pharmacological studies of grandinin. Phytotherapy Research, 17(7), 767-773. DOI:10.1002/ptr.1214

Morales-Rico, C. L., Marrero-Delange, D., González-Canavaciolo, V. L., Quintana-Ramos, F., & González-Cornejo, I. (2012). Composición química del aceite esencial de las partes aéreas de Melaleuca quinquenervia. Revista CENIC Ciencias Químicas, 43, 1-2. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/236876708

Morales-Rico, C. L., Marrero-Delange, D., González-Canavaciolo, V. L., Quintana-Ramos, F., González-Cornejo, I., & Dago-Morales, A. (2015). Análisis multivariable de la composición química del aceite esencial de hojas de Melaleuca quinquenervia que crece en Cuba. Boletín Latinoamericano y del Caribe de Plantas Medicinales y Aromáticas, 14(5), 374-384. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/282670342

Morton, J. F. (1981). Atlas of medicinal plants of Middle America: Bahamas to Yucatan. Springfield, Illinois, USA: Charles C. Thomas.

Moudachirou, M., Gbenou, J. D., Garneau, F.-X., Jean, F.-I., Gagnon, H., Koumaglo, K. H., & Addae-Mensah, I. (1996). Leaf oil of Melaleuca quinquenervia from Benin. Journal of Essential Oil Research, 8(1), 67-69. DOI: 10.1080/10412905.1996.9700557

Padovan, A., Keszei, A., Köllner, T. G., Degenhardt, J., & Foley, W. J. (2010). The molecular basis of host plant selection in Melaleuca quinquenervia by a successful biological control agent. Phytochemistry, 71(11-12), 1237-1244. DOI: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2010.05.013

Philippe, J., Goeb, P., Suvarnalatha, G., Sankar, R., & Suresh, S. (2002). Chemical composition of Melaleuca quinquenervia (Cav.) S. T. Blake leaf oil from India. Journal of Essential Oil Research, 14(3), 181-182. DOI: 10.1080/10412905.2002.9699817

Pino, J., Marbot, R., & Vázquez, C. (2004). Volatile components of the fruits of Vangueira madagascariensis J. F. Gmel. from Cuba. Journal of Essential Oil Research, 16(4), 302-304. DOI: 10.1080/10412905.2004.9698727

Ramanoelina, P. A. R., Bianchini, J.-P., Andriantsiferana, M., Viano, J., & Gaydou, E. M. (1992). Chemical composition of niaouli essential oils from Madagascar. Journal of Essential Oil Research, 4(6), 657-658. DOI: 10.1080/10412905.1992.9698155

Ramanoelina, P. A. R., Viano, J., Bianchini, J.-P., & Gaydou, E. M. (1994). Occurrence of various chemotypes in niaouli (Melaleuca quinquenervia) essential oils from Madagascar using multivariate statistical analysis. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 42(5), 1177-1182. DOI: 10.1021/jf00041a024

Seligmann, O., & Wagner, H. (1981). Structure determination of melanervin, the first naturally occurring flavonoid of the triphenylmethane family. Tetrahedron, 37(15), 2601-2606. DOI:10.1016/S0040-4020(01)98963-X

Siddique, S., Mazhar, S., Bareen, F.-E., & Parveen, Z. (2018). Chemical characterization, antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of essential oil from Melaleuca quinquenervia leaves. Indian Journal of Experimental Biology, 56(9), 686-693. Retrieved from http://nopr.niscair..res.in/handle/123456789/44995

Silva, C. J., Barbosa, L. C. A., Maltha, C. R. A., Pinheiro, A. L., & Ismail, F. M. D. (2007). Comparative study of the essential oils of seven Melaleuca (Myrtaceae) species grown in Brazil. Flavour and Fragrance Journal, 22(6), 474-478. DOI: 10.1002/ffj.1823

Stenhagen, E., Abrahamsson, S., & McLafferty, F. W. (1974). Registry of Mass Spectral Data. New York, NY, USA: John Wiley & Sons.

Swigar, A. A., & Silvertein, R. M. (1981). Monoterpenes. Infrared, Mass, 1N-NMR, and 13C-NMR Spectra, and Kováts Indices. Milwaukee, WI, USA: Aldrich Chemical Company Inc.

Trilles, B., Bouraïma-Madjebi, S., & Valet, G. (1999). Melaleuca quinquenervia (Cavanilles) S. T. Blake, Niaouli. In Southwell, I., & Lowe, R. (Eds.). Tea tree: the genus Melaleuca. — (Medicinal and aromatic plants: industrial profiles; v. 9). (pp. 237-245). Amsterdam, Netherlands: Harwood Academic Publishers.

Trilles, B., Bombarda, I., Bouraïma-Madjebi, S., Raharivelomanana, P., Bianchini, P., & Gaydou, E. M. (2006). Occurrence of various chemotypes in niaouli [Melaleuca quinquenervia (Cav.) S. T. Blake] essential oil from New Caledonia. Flavour and Fragrance Journal, 21(4), 677-682. DOI: 10.1002/ffj.1649

van Den Dool, H., & Kratz, P. D. (1963). A generalization of the retention index including linear temperature programmed gas-liquid partition chromatography. Journal of Chromatography A, 11, 463-471. DOI: 10.1016/S0021-9673(01)80947-X

Vanaclocha, B., & Cañigueral, S. (2003). Fitoterapia. Vademécum de prescripción. Barcelona, Spain: Masson, S. A.

Wallace, W. E. (2019). Mass spectra (by NIST Mass Spec Data Center). In P. J. Linstrom & W. G. Mallard (Eds.), Chemistry WebBook, NIST Standard Reference Database Number 69. Gaithersburg, MD, USA: National Institute of Standards and Technology. Retrieved from http://webbook.nist.gov

Wagner, H., Seligmann, O., Hörhammer, H.-P., Chari, V. M., & Morton, J. F. (1976). Melanervin aus Melaleuca quinquenervia, ein Flavanon mit Triphenylmethanstruktur. Tetrahedron Letters, No. 17, 1341-1344.

Wheeler, G. S. (2006). Chemotype variation of the weed Melaleuca quinquenervia influences the biomass and fecundity of the biological control agent Oxyops vitiosa. Biological Control, 36(2), 121-128. DOI: 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2005.10.005

Wheeler, G. S., Pratt, P. D., Giblin-Davis, R. M., & Ordung, K. M. (2007). Infraspecific variation of Melaleuca quinquenervia leaf oils in its naturalized range in Florida, the Caribbean, and Hawaii. Biochemical Systematics and Ecology, 35(8), 489-500. DOI: 10.1016/j.bse.2007.03.007

Zoghbi, M. G. B., Andrade, E. H. A., Santos, A. S., Silva, M. H. L., & Maia, J. G. S. (1998). Essential oils of Lippia alba (Mill.) N. E. Br growing wild in the Brazilian Amazon. Flavour and Fragrance Journal, 13(1), 47-48. DOI: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1026(199801/02)13:1<47::AID-FFJ690>3.0.CO;2-0

Edited by Melissa Garro Garita.