Avifaunal characterization of Corral de Piedra Palustrine Wetland,

Nicoya, Costa Rica

Roberto Vargas-Masís1,2*, Lilliana Piedra-Castro1& Juan Bravo-Chacón3

1. Escuela de Ciencias Biológicas. Universidad Nacional. Heredia, Costa Rica; robvarmas@gmail.com, lilliana.piedra.castro@una.cr,

juanbrv@gmail.com

2. Vicerrectoría de Investigación, Universidad Estatal a Distancia. Sabanilla, Costa Rica; rovargas@uned.ac.cr

3. Centro Mesoamericano de Desarrollo del Trópico Seco (CEMEDE). Nicoya, Costa Rica; juanbrv@gmail.com

* Corresponding author: robvarmas@gmail.com

Received 30-I-2017 • Corrected 24-IV-2017 • Accepted 22-V-2017

ABSTRACT: Wetlands maintain high biodiversity and provide important habitat for many bird species, but now have strong pressure from anthropogenic activities. Birds in wetlands are important indicators of environmental changes and our goal was to characterize the bird community in the wetlands Palustrine Corral de Piedra as a mechanism for conservation of tropical dry forest of Costa Rica. We used point counts to describe bird richness and abundance in open (lakes and flooded grasslands) and wooded areas. We described habitat use and microhabitats, trophic guilds, biogeographic distribution and status in Costa Rica. We recorded 83 species of resident birds belonging to 36 families, of which 65 are resident species and 18 have some migratory status in Costa Rica. Secondary consumer species of small vertebrates corresponded to 45,8% and primary consumers were 25,3%. The birds mainly used trees for perching but use emergent shrubs, floating vegetation and water. We found a large number of Egrets, Flycatchers and Hawks playing important roles as pollinators, seed dispersers and predator is adding significant value to the ecological dynamics of forests and lakes in the area. Corral de Piedra has special importance as a site for the establishment of migratory birds and large number of resident species of conservation concern. We consider that joint efforts between residents and researchers are an important tool for bird conservation in the region.

Keywords: wetlands, birds, conservation, richness, habitat, trophic guilds.

Biodiversity in wetlands is high and the natural resources in the ecosystem determine its use (Iannacone et al., 2010). Actually, they have strong pressures by anthropogenic activities (Santos & Tellería, 2006), pollution and fragmentation, which have altered the natural conditions of these ecosystems (Mora, Rodríguez & López, 2003).

Costa Rica has over 350 wetlands that ecosystems are protecting by national and international environmental legislation. These wetlands have different degrees of protection and some of them reach the level of National Park. The Arenal Tempisque Conservation Area has the most important wetlands area in Costa Rica and some of them have international designation how RAMSAR sites (Alvarado-Quesada, 2006; Sassa et al., 2015).

The high productivity of wetland ecosystems, beside with the scenic beauty and high diversity of flora and fauna, provide refuge to bird species, nesting sites, food and are important points of concentration during the annual migrations (Carmona-lslas et al., 2013; Vizcarra, 2008).

Birds are common group in conservation studies. Because have been widely used as habitat indicators (Figuerola & Green, 2003; Schulze et al., 2004; Brandolin, Martori & Ávalos, 2007). This group presents particular significance in wetlands as indicators of processes or changes, the natural relationships with other organisms, population’s sizes, hunted susceptibility and restricted distribution (Blanco, 1999). However, only periodic monitoring of populations allows detecting changes due to modifications in these ecosystems (Vizcarra, 2008; Goldsmith, 2012; Furness & Greenwood, 2013).

Considering the importance to birds as indicators of environmental changes (Gregory et al., 2003) our objective was to characterize the bird community in Corral de Piedra Palustrine Wetland determining the diversity and habitat use of avifauna as mechanism for conservation of wetlands in tropical dry forests of Costa Rica.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

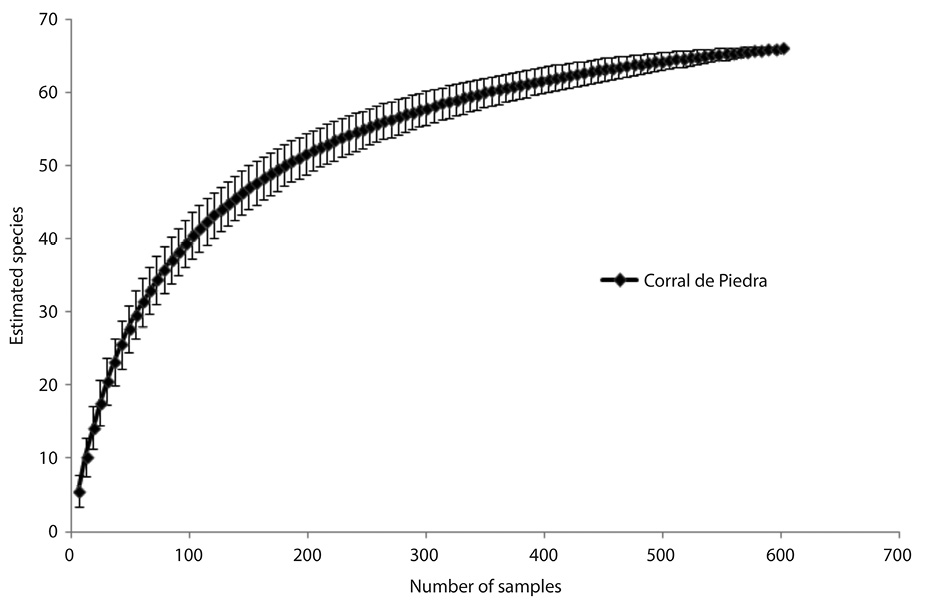

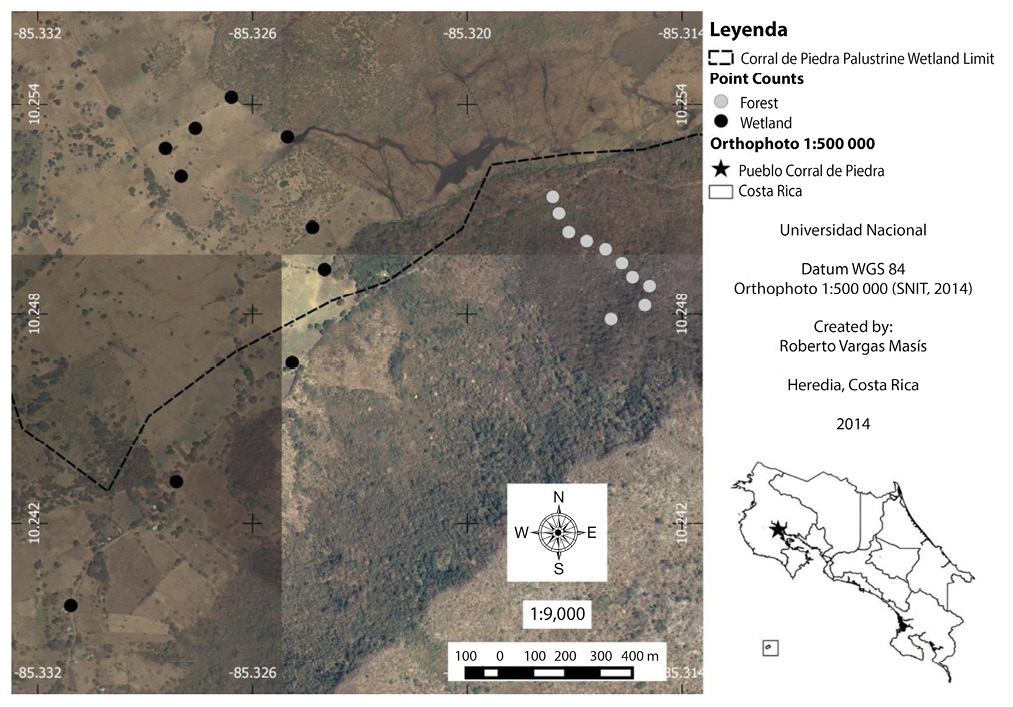

Study site: Corral de Piedra Palustrine Wetland is located in the Tempisque Conservation Area. It´s a drainage basin of a reservoir (Corral de Piedra marsh) and surrounding flooded areas which connected represents about 2,368 ha, from which approximately 400 ha correspond to the mirror water (Umaña, 2007).

The wetland is characterized by a seasonal marsh between fresh and brackish water located on the right margin of the Tempisque river, to the south of the lagoons of Palo Verde National Park (Fig. 1). It´s located around of 2m.a.s.l., the average temperature of 29°C that becomes a marsh ecological system, which protects the habitat, and nesting and feeding site for waterbirds (Umaña, 2007; WingChing-Jones & Leal-Rivera, 2014).

The vegetation is composing by species of aquatic ecosystem as Palo Verde (Parkinsonia aculeata) and southern cattail (Typha domingensis). The riparian forest cover present strong associations with species as the Yellow Mombin (Spondias mombin), Tempisque (Sideroxylon capiri) and others (Umaña, 2007).

The wetland is into the Diriá Biological Corridor (SINAC, 2011) that another protected areas as Barra Honda National Park and Palo Verde National Park. These places have important functions as corridor for wildlife (Rodríguez, 2001). The Corral de Piedra wetland was declaring by act (DE 22898 - MIRENEM) as Palustrine Wetland, and is part of the RAMSAR site Palo Verde National Park, was avow Ramsar Sites in January 1990.

Bird sampling: We evaluated bird community composition of the Corral de Piedra Palustrine Wetland from July to October 2011 considering open areas (as lagoons and flooded pastures) and forested areas (trail to Corral de Piedra).

We did 10 points of bird counts in the wetland (open areas) and 10 points in forest areas. Point counts separated by 100 m in open areas and 50 m in forested areas using a detection radius of 50 m according to recommendations by Bibby, burgess and Hill (1992), Ralph et al. (1996), Whitacre (1997) and Sutherland (2006). The difference of the point count distance in the areas was relating with the loss of detectability between habitats where the number of species and individuals detected depends to the dense of vegetation (Anderson et al., 2015).

On each fixed-radius point counts, all individuals seen or heard calling during the survey period were recorded and the numbers of individuals per species were estimated in open and forest areas between 5:00 to 9:00 hours during 6 minutes where the counting efficiency is maximized (Thompson & Schwalbach, 1995).

We report different species from casual observations in the border of the lagoon and wooded areas. However, these data were not considering in the diversity and abundance analysis.

Ecological characterization: We describe ecological variables of bird species considering the studies of Pedroso Jr. (2003), Moreno-Rueda (2006) and parameters proposed by Ramsar (2006) to wetlands (Table 1). The habitat, richness and abundance were using in the statistical analyses while the remaining were only used in the ecological characterization of the avifauna.

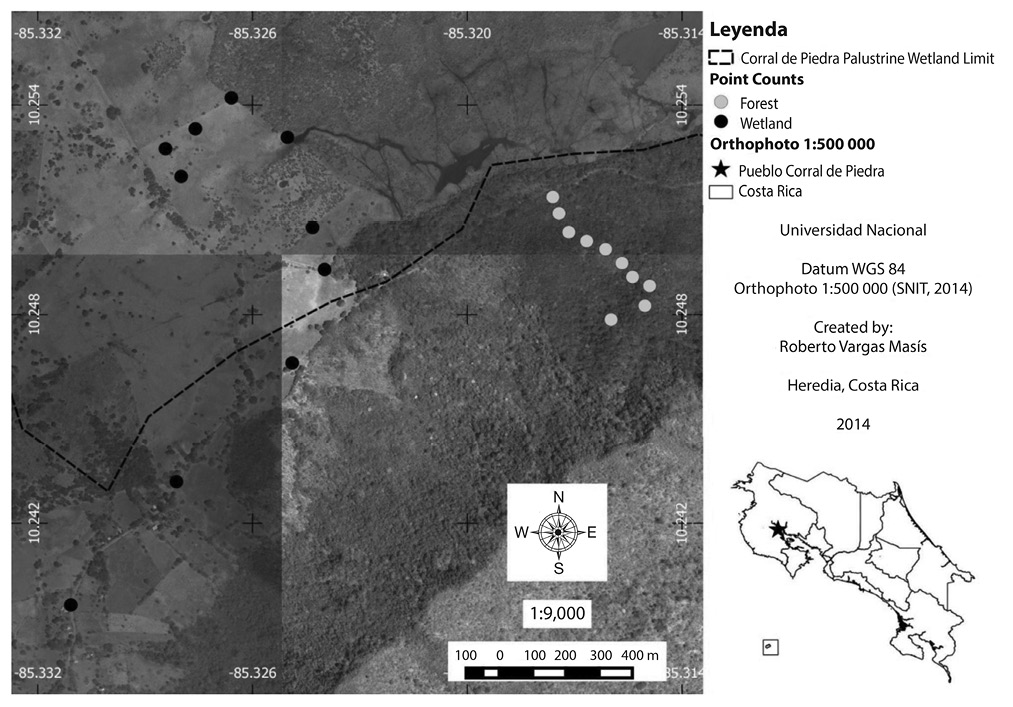

Data analysis: We test the evidence of difference between alpha diversity in the two sample areas at Corral de Piedra Palustrine Wetland using diversity and abundance data with the open code test by Cichini (2011) that is an adaptation to the permutation test from the PAST Software (Hammer & Harper, 2006) using the program R (R Development Core Team, 2008). We constructed rarefaction curves to represent the distribution of bird species richness in relation to our sampling effort and estimated the probably number species detected (Iannacone et al., 2010).

RESULTS

We recorded 83 bird species belonging to 36 families (Table 2). The most abundant families were Ardeidae (11 species) and five species to Accipitridae, Columbidae, Psittacidae, Icteridae and Tyrannidae. The 79% (64 species) have resident status in Costa Rica for example Aramus guarauna, Herpetotheres cachinnans, and Dendrocygna autumnalis. The 14,8% (12 species) have resident-migratory status such as Cathartes aura, Egretta tricolor and Mycteria americana. The 4,9% (4 species) have migratory status as Actitis macularius, Anas discors and Ardea herodias.

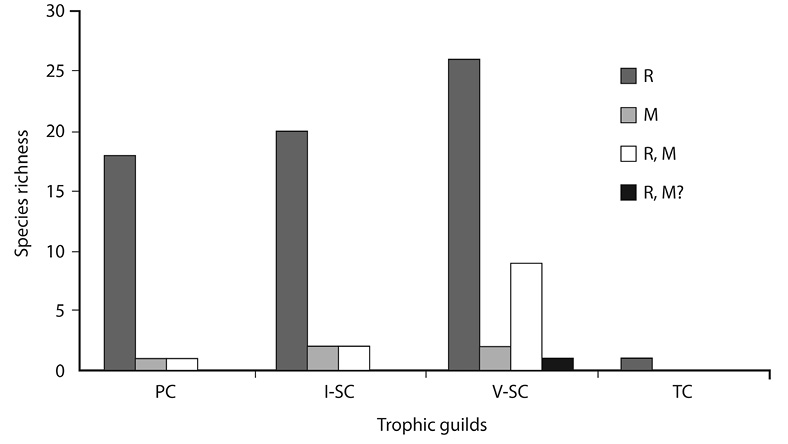

According to the trophic guilds (Fig. 2), the 25,3% corresponds to primary consumers (21 species such as Columbina passerina, Amazona albifrons and Amazilia rutila). The 28,9% are secondary consumers that feed on invertebrates (25 species represented by Agelaius phoeniceus, Bubulcus ibis and Colinus cristatus) and the secondary consumers species of small vertebrates were represented by 45,8% (37 species, including Anhinga anhinga, Rupornis magnirostris and Pitangus sulfuratus).

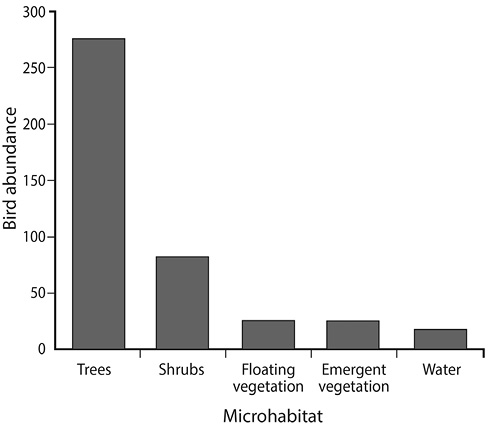

The birds in Corral de Piedra Palustrine Wetland area use primarily trees to perch (65,7% of the observations). However, an important number were using shrubs (19,3% of total observations), 4,6% use emergent and floating vegetation and only the 4,3% were observed using the water as main microhabitat (Fig. 3).

The majority of species in Corral de Piedra were distributed throughout the national territory (43,2% of species). The 29,6% are mainly distributed in the Northwestern Pacific Lowlands (Guanacaste) and neighboring areas such as Amazona auropalliata, Burhinus bistriatus, Calocitta formosa, Morococcyx erythropygius and Jabiru mycteria. The 21% were distributed in Pacific and Caribbean slopes. In addition, the remaining 6,2% were distributed exclusively within the Pacific slope. Some of these species have been expanding their distribution in Central Valley or North and Caribbean areas of Costa Rica (Alvarado-Quesada et al., 2009).

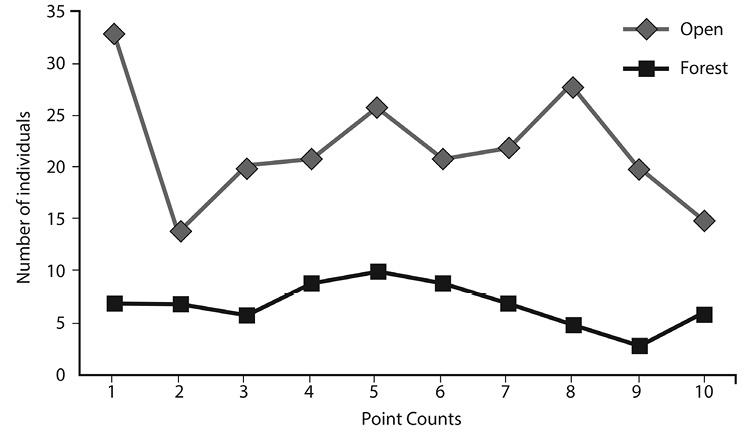

Diversity and abundance analysis: We recorded 561 individuals in Corral de Piedra Palustrine Wetland during the study period. The 87,5% (491 observations) were observing in open areas and just the 12,5% in forest areas (70 observations) (Fig. 4).

The species richness in open areas compared with forest areas was different (Wilcoxon = 4782,5, p-value < 0,0001). We found more species at open areas with 69 species observed such as Porphyrula martinica, Rosthramus sociabilis and Platalea ajaja as representative species to flooded areas, the forest area have 22 species such as Cantorchilus pleurostictus, Amazilia rutila and Amazona albifrons. We identified 15 species inhabiting both areas such as Icterus pustulatus, Pachyramphus aglaiae and Dives dives.

We obtained a good characterization of richness to avifauna of Corral de Piedra Palustrine Wetland, according to the rarefaction curve (Fig. 5) that show high number of species recorded by the study according the accumulation of species and the number of samples.

Species with particular ecological importance: At Corral de Piedra Palustrine Wetland were located individuals of Parabuteo unicinctus, which has a restricted distribution in Costa Rica to ecosystems of Northwestern Pacific Lowlands (Garrigues & Dean, 2014).

Other particular species are Herpetotheres cachinnans that feeds mainly on snakes and Calocitta formosa that actually have small populations in Costa Rica and expand their distribution to Central Valley and open areas for increment of deforestation (Ellis, 2010). Ants (Flaspohler & Laska, 1994; Young, Kaspari & Martin, 1990) notattack Campylorhynchus rufinucha and Icterus pustulatus whenbuild nests. There birds use almost exclusively on Acacia spp.

Likewise, species with low populations were found as Jabiru mycteria and Platalea ajaja (protected by the Conservation Wildlife Law No. 7317, the Organic Environmental Law No. 7554 and Decree N° 26435-MINAE, Appendix I of CITES), however according to IUCN (2011) found under the category of least concern.

DISCUSSION

Birds populations in Corral de Piedra Palustrine Wetland have a particular importance in conservation efforts in the wetlands of the tropical dry forests in Costa Rica that have been considered as the ecosystem with less attention in the tropics (Sánchez-Azofeifa et al., 2005). The bird species observe in the wetland have importance as seed dispersers, pollinators or pest controllers and need to be protected to maintain the ecological relationships through the conservation of such populations (Sekercioglu, 2006).

The richness that presented Ardeidae, Tyrannidae and Accipitridae families can be explained by its wide distribution, the greater number of species and individuals at national level (Stiles & Skutch, 2007), these species have habits, behaviors, morphological and ecological characteristics that allow its easy detection (Nadeau & Conway, 2002; Thompson, 2002; Weller, Blackwell & Moller, 2012). The open areas increase the heterogeneity of microhabitats (Bojorges, 2011), allowing the establishment of greater number of species and spots which provides roosting sites, protection, nesting and feeding, among others (Enriquez et al., 2007).

Wetlands and slightly disturbed areas have a high number of species such as insectivorous, because these areas maintain abundant of invertebrates, which are secondary consumers’ birds (Kyerematen et al., 2014). Resident species play important roles as pollinators and fruit dispersers in the ecosystem thereby add significant value to the ecological dynamics of forests in the area (Carranza & Esteves, 2008), and particular importance of conservation to tropical dry forests in Costa Rica and the Central American region.

It is important to notice that Corral de Piedra wetland, surrounding areas are very important by migratory birds, and large number of residents who have a particular conservation status such as Jabiru mycteria, so prioritize efforts in these areas is critical for the maintenance of their populations (Orias, 2016).

The characteristics and proximity of Corral de Piedra with other wetlands causes that abundance of some species exceeds others, such as D. autumnalis and A. guarauna, species that prefer flooded areas (Trama et al., 2009). Furthermore, the presence of open areas such as pastures, allowing the establishment of great quantities of Crotophaga sulcirostris and other generalists species.

The adaptations present in birds to get their food is related to both the presence of different microhabitats and the availability of resources in the ecosystem (Shochat et al., 2010; Weller et al., 2012) which vary depending on site physicochemical variables, this could explain some way diversity Ardeidae family on the site by the presence of aquatic habitat. This family has many adaptations that allow it to colonize different niches such as peaks and legs.

The diversity of resident species (especially native) is high in wetlands (Weller et al., 2012). Corral de Piedra Palustrine Wetland compared to other protected areas as Palo Verde National Park with 300 bird species (60 resident and migratory waterbirds) present a high number of resident species that is relevant to maintain stability of bird populations in the area (Adair et al., 2012). The maintenance and availability of resources are so important. Because not affect the balance in the ecosystem and birds represent a group with particular characteristics and importance to monitoring changes or effects in habitats (Koskimies, 1989; Tobias, Sekercioglu & Vargas, 2013).

Corral de Piedra palustrine Wetland is an area with strong environmental pressures (drought and wildfires, water quality) and anthropogenic (hunting, deforestation and water pollution) also is affected by the presence of Typha dominguensis in the lagoons and affect water mirrors, which use large numbers of resident and migratory birds (Bufford & Gonzalez, 2012). Corral de Piedra people join efforts in wetland conservation. In addition, integrated in water management processes and collaborative research (Rojas-Cantillano et al., 2014).

We consider that joint efforts between residents and researchers are an important tool for bird conservation in the region because a lot of species of birds in the wetland are representative of the dry forest ecosystem, which in Central America is recognized as one of the last remnants of this ecosystem.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are thankful with the park rangers and neighbors in Corral de Piedra for their cooperation during the investigation. We thank Francisco Monge, Kattia Alpizar and Sara Estrada for their assistance during sampling; and Centro Mesoamericano de Desarrollo Sostenible del Trópico Seco (CEMEDE) for support during the research.

REFERENCES

Adair, C., Batista-Mora, N., Laing, J., Rogers, Z., & Ankersen, T. (2012). Restoration of the Wetlands in Palo Verde National Park: A Legal and Ecological Analysis. Final Report to Joint Program in Environmental Law. University of Florida and University of Costa Rica. Retrieved from https://www.law.ufl.edu/_pdf/academics/academic-programs/study-abroad/costa-rica/Ramsar-Report.pdf

Alvarado-Quesada, G. M. (2006). The importance of Costa Rica for resident and migratory waterbirds. Waterbirds around the world. G.C. Boere, C.A. Galbraith, & D.A. Stroud (eds.). Edinburgh, UK: The Stationery Office.

Alvarado-Quesada, G., Bolaños-Redondo, S. E., & Solano-Zárate, J. (2009). Ampliación del ámbito de distribución del Alcaraván Burhinus bistriatus (Aves: Burhinidae) en Costa Rica. Brenesia, 71-72, 81-82.

Anderson, A. S., Marques, T. A., Shoo, L. P., & Williams, S. E. (2015). Detectability in Audio-Visual Surveys of Tropical Rainforest Birds: The Influence of Species, Weather and Habitat Characteristics. PLoS ONE, 10(6), e0128464. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0128464

Bibby, C. J., Burgess, N. D., & Hill, D. A. (1992). Bird Census Techniques. London: Academic.

Blanco, D. E. (1999). Los humedales como hábitat de aves acuáticas. Tópicos sobre humedales subtropicales y templados de Sudamérica. Oficina Regional de Ciencia y Tecnología de la UNESCO para América Latina y el Caribe-ORCYT-Montevideo–Uruguay, 219-228.

Brandolin, P., Martori, R., & Ávalos, M. (2007). Variaciones temporales de los ensambles de aves de la Reserva Natural de Fauna Laguna La Felipa (Córdoba, Argentina). El Hornero, 22(1), 1-8.

Bojorges, J. C. (2011). Riqueza de especies de aves de la microcuenca del río Cacaluta, Oaxaca, México. Uciencia, 7, 1, 87-95.

Bufford, J. L., & González, E. (2012). Manejo del humedal Palo Verde y de las comunidades de aves asociadas a sus diferentes hábitats. Ambientales, 43: 7-16.

Carmona-lslas, C., Bello-Pineda, J., Carmona, R., & Velarde, E. (2013). Modelo espacial para la detección de sitios potenciales para la alimentación de aves playeras migratorias en el noroeste de México. Huitzil, ١٤(1), 22-36. Retrieved from http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1870-74592013000100007&lng=es&tlng=es.

Carranza, J., & Estéves, J. (2008). Ecología de la polinización de Bromeliaceae en el dosel de los bosques neotropicales de montaña. Bol.cient.mus.hist.nat., 12, 38-47.

Cichini, K. (2011). Test Difference between Diversity-Indices of Two Samples with Abundance Data. Biobucket blog. Retrieved from http://thebiobucket.blogspot.com/2011/04/test-difference-between-diversity.html#more

Ellis, J. M. S. (2010). White-throated Magpie-Jay (Calocitta formosa), Neotropical Birds Online. T. S. Schulenberg (ed.). Ithaca: Cornell Lab of Ornithology; Retrieved from Neotropical Birds Online: http://neotropical.birds.cornell.edu/portal/species/overview?p_p_spp=514796.

Enríquez, M.L., Sáenz, J.C., & Ibrahim, M. (2007). Riqueza, abundancia y diversidad de aves y su relación con la cobertura arbórea en un agropaisaje dominado por la ganadería en el trópico subhúmedo de Costa Rica. Agroforestería en las Américas, 45, 49-57.

Figuerola, J., & Green, A. J. (2003). Aves acuáticas como bioindicadores en los humedales. In Ecología, manejo y conservación de los humedales (pp. ٤٧-٦٠). Instituto de Estudios Almerienses.

Flaspohler, D.J., & Laska, M.S. (1994). Nest site selection by birds in Acacia trees in a Costa Rican dry deciduous forest. Wilson Bulletin, 106, 162-165.

Furness, R., & Greenwood, J. J. (2013). Birds as monitors of environmental change. Springer Science & Business Media.

Garrigues, R., & Dean, R. (2014). The birds of Costa Rica field guide. A Zona Tropical Publication. Second edition. Ithaca, New York, EEUU: Cornell University.

Gregory, R. D., Noble, D., Field, R., Marchant, J., Raven, M., & Gibbons, D. W. (2003). Using birds as indicators of biodiversity. Ornis hungarica, 12(13), 11-24.

Goldsmith, F. B. (2012). Monitoring for conservation and ecology (Vol. ٣). Springer Science & Business Media.

Hammer, Ø., & Harper, D. A. T. (2006). Paleontological Data Analysis. United Kindom: Blackwell Publishing.

Iannacone, J., Atasi, M., Bocanegra, T., Camacho, M., Montes, A., Santos, S., Zúñiga, H., & Alayo, M. (2010). Diversity of birds in Pantanos de Villa Wetland, Lima, Peru: period 2004-2007. Biota Neotrop, 10, 2, 295-304.

Kyerematen, R., Acquah-Lamptey, D., Owusu, E. H., Anderson, R. S., & Ntiamoa-Baidu, Y. (2014). Insect diversity of the muni-pomadze ramsar site: An important site for biodiversity conservation in Ghana. Journal of Insects, 2014. doi: 10.1155/2014/985684

Koskimies, P. (1989). Birds as a tool in environmental monitoring. Annal Zoologica Fennici, 26, 153-166.

Mora, J. M., Rodríguez, M., & López, L. (2003). Sondeo ecológico rápido y monitoreo de especies indicadoras en el Parque Nacional Tortuguero. Informe técnico para el Área de conservación Tortuguero. Sistema Nacional de Áreas Protegidas (SINAC), Costa Rica.

Moreno-Rueda, G. (2006). El comportamiento de las aves como herramienta para su identificación. Acta Granatense, 4(5), 85-93.

Nadeau, C. P., & Conway, C. J. (2012). Field evaluation of distance-estimation error during wetland-dependent bird surveys. Wildlife Research, 39, 4, 311-320.

Obando-Calderón, G., Chaves-Campos, J., Garrigues, R, Montoya, M., Ramírez, O., & Zook, J. (2015). Lista Oficial de las Aves de Costa Rica - Actualización 2016. Comité de Especies Raras y Registros Ornitológicos (Comité Científico), Asociación Ornitológica de Costa Rica. San José, Costa Rica. Revista Zeledonia, 19-2.

Orias, J. V. (2016). El jabirú (Jabiru mycteria) en Costa Rica: población y conservación. Biocenosis, 22(1-2).

Pedroso Jr., N. (2003). Microhabitat occupation by birds in a Restinga Fragment of Paraná Coast, PR, Brazil. Brazilian archives of biology and technology, 46(1), 83-90.

R Development Core Team (2008). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. ISBN 3-900051-07-0. Retrieved from http://www.R-project.org.

Ralph, C. J., Geupel, G., Pyle, P., Martin, T., De Sante, D., & Milá, B. (1996). Manual de métodos de campo para el monitoreo de aves terrestres. Gen. Tech. Rep. PSW-GTR-159. Albany, CA. Pacific Southwest Research Station, Forest Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture.

RAMSAR. (2006). La Convención sobre los humedales. Criterios para la identificación de humedales de importancia internacional. Documento informativo Ramsar Nº 5. Retrieved from http://www.ramsar.org/pdf/about/info2007sp-05.pdf

Rojas-Cantillano, D., Coto-Campos, J. M., Benavides-Benavides, C., Salgado-Silva, V. & Jiménez-Torres, J. (2014). Percepción de los pobladores sobre cambios en el entorno en Corral de Piedra, Nicoya, Guanacaste. Biocenosis, 29(1-2): 90-96.

Sánchez-Azofeifa, G. A., Kalacska, M., Quesada, M., Calvo-Alvarado, J. C., Nassar, J. M., & Rodríguez, J. P. (2005), Need for Integrated Research for a Sustainable Future in Tropical Dry Forests. Conservation Biology, 19, 285–286. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2005.s01_1.x

Santos, T., & Tellería, J. L. (2006). Pérdida y fragmentación del hábitat: efecto sobre la conservación de las especies. Ecosistemas, 15(2), 3-12.

Sasa, M., Bonilla, F., Armengol, X., Mesquita-Joanes, F., Piculo, R., Rojo, C., Monros, J.S., & Rueda, R.M. (2015). Seasonal wetlands in the Pacific coast of Costa Rica and Nicaragua: Environmental characterization and conservation state. Limnetica, 34, 1, 1-16.

Schulze, C. H., Waltert, M., Kessler, P. J., Pitopang, R., Veddeler, D., Mühlenberg, M., Gradstein, R.; Leuschner, C.; Steffan-dewenter, I. & Tscharntke, T. (2004). Biodiversity indicator groups of tropical landuse systems: comparing plants, birds, and insects. Ecological applications, 14(5), 1321-1333.

Sekercioglu, C. H. (2006). Increasing awareness of avian ecological function. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 21(8),464–471. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2006.05.007

Shochat, E., Lerman, S., & Fernandez-Juricic, E. (2010). Birds in Urban Ecosystems: Population Dynamics, Community Structure, Biodiversity, and Conservation. Agronomy, 55, 75-86.

SINAC. (2011). Sistema Nacional de Áreas Protegidas: Número y tamaño de ASP`s terrestres y marinas, legalmente declaradas. Retrieved from http://www.sinac.go.cr/planificacionasp.php

SNIT. (2014). IGN Ortofotos 1:5000. Servicios OGC. Sistema Nacional de Información Territorial. Instituto Geográfico Nacional. Retrieved from http://www.snitcr.go.cr/servicios_ogc_completo

Stiles, F. G. (1985). Conservation of forest birds in Costa Rica: Problems and perspectives, p 141 – 168. In A.W. Diamond y T.S. Lovejoy (eds). Conservation of tropical forest birds. Technical Publication N° 4. Cambridge: International Council for Birds Preservation. England. 318 pp.

Stiles, F. G., & Skutch, A. (2007). Guía de aves de Costa Rica. 4ta edición, Santo Domingo de Heredia, Costa Rica: INBio.

Sutherland, W. (2006). Ecological Census Techniques a handbook. Second Edition. New York, United States of America: Cambridge University.

Thompson, W. L. (2002). Towards reliable bird surveys: Accounting for individuals present but not detected. The Auk, 119(1), 18-25.

Thompson F. R., & Schwalbach, M. J. (1995). Analysis of Sample Size, Counting Time, and Plot Size from an Avian Point Count Survey on Hoosier National Forest, Indiana1. USDA Forest Service Gen. Tech. Rep. PSW-GTR-149. Retrieved from: https://www.fs.fed.us/psw/publications/documents/gtr-149/pg45_48.pdf

Tobias, J. A., Sekercioglu, C. H., & Vargas, F. H. (2013). Bird conservation in tropical ecosystems: challenges and opportunities. In: MacDonald, D. (Ed.), Key Topics in Conservation Biology, vol. 2. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Trama, F. A., Rizo-Patrón, F. L., Kumar, A., González, E., & Somma, D. (2009). Wetland cover types and plant community changes in response to cattail-control activities in the Palo Verde Marsh, Costa Rica. Ecological Restoration, 27(3), 278-289.

UICN. (2011). IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2011.1. Retrieved from www.iucnredlist.org.

Umaña, E. (2007). Fluctuaciones temporales en la Diversidad y Abundancia Relativa de Aves Acuáticas en el Refugio Nacional de Vida Silvestre Laguna Mata Redonda y Humedal Corral de Piedra, Costa Rica. Tesis de Licenciatura en Manejo de Recursos Naturales. Universidad Nacional de Costa Rica. 75 p.

Vizcarra, J. K. (2008). Composición y conservación de las aves en los humedales de Ite, suroeste del Perú. Boletín Chileno de Ornitología, 14(2), 59-80.

Weller, F., Blackwell, G., & Moller, H. (2012). Detection probability for estimating bird density on New Zealand sheep and beef farms. New Zealand Journal of Ecology, 36(3), 371-381.

Whitacre, D. F. (1997). Un Programa de Monitoreo Ecológico para la Reserva de la Biósfera Maya. Documento Técnico de la Agencia de los Estados Unidos para el Desarrollo Internacional (USAID) y el Consejo Nacional de Áreas Protegidas de Guatemala (CONAP).

WingChing-Jones, R., & Leal- Rivera, J. C. (2014). Valoración agronómica y nutricional de la Typha domingensis, como alternativa de alimentación en animales rumiantes. Nutrición Animal Tropical, 8(2), 24-35.

Young, B. E., Kaspari, M., & Martin, T. E. (1990). Species-specific nest site selection by birds in ant-acacia trees. Biotropica, 22, 310-315.

RESUMEN: Caracterización de la avifauna del Humedal Palustrino Corral de Piedra, Nicoya, Costa Rica. Los humedales mantienen una alta biodiversidad y proporcionan un hábitat importante para muchas especies de aves, pero enfrentan fuertes presiones por actividades antropogénicas. Las aves en los humedales son importantes indicadores de cambios ambientales y nuestro objetivo fue caracterizar la comunidad de aves en el Humedal Palustrino Corral de Piedra como mecanismo de conservación del bosque tropical seco de Costa Rica. Utilizamos puntos de conteo para describir la riqueza y abundancia de aves en áreas abiertas (lagunas y pastizales inundados) y zonas boscosas. Describimos el uso del hábitat y microhábitats, gremios tróficos, distribución biogeográfica y estatus en Costa Rica. Registramos 83 especies de aves que corresponden a 36 familias, de las cuales 65 son especies residentes y 18 poseen algún estatus migratorio en Costa Rica. Las especies consumidoras secundarias de pequeños vertebrados correspondieron al 45,8% y los consumidores primarios fueron el 25,3 %. Las aves utilizan principalmente árboles para posarse, pero utilizan también arbustos emergentes, vegetación flotante y agua. Encontramos un gran número de garzas, atrapamoscas y halcones que desempeñan papeles importantes como polinizadores, depredadores y dispersores de semillas de frutas, añadiendo un valor significativo a la dinámica ecológica de los bosques y lagunas de la zona. Corral de Piedra posee especial importancia porque permite el establecimiento de las aves migratorias y gran número de especies residentes que tienen un estado de conservación particular. Consideramos que los esfuerzos conjuntos entre residentes e investigadores son una herramienta importante para la conservación de aves en la región.

Palabras clave: humedal, aves, conservación, riqueza, hábitat, gremios tróficos.

Fig. 1. Points counts in Corral de Piedra Palustrine Wetland between July and October 2011 (SNIT, 2014).

TABLE 1.

Variables recorded of birds in Corral de Piedra Palustrine Wetland.

|

Features |

Description |

|

Habitat use |

Open: areas with a few trees and dominated by pastures, ponds and roads. Forest: areas with dominance of trees (DAP ≥15 cm). |

|

Microhabitat use |

Location of birds in water, floating vegetation, emergent vegetation, shrubs and trees. |

|

Trophic guilds |

The priority food group according to Skutch (1985). Where PC: Primary consumer; I-SC: Invertebrate secondary consumer; V-SC: Vertebrate secondary consumer. |

|

Biogeographic distribution in Costa Rica |

Distribution in Costa Rica according to Garrigues & Dean (2014) and Stiles & Skutch (2007). Where G: Species distributed only in the Guanacaste area, P: Species distributed in the Pacific slope; PC: Species distributed in the Pacific and Caribbean slopes; A: Species distributed in Costa Rica. |

TABLE 2

Bird species list observed in the Corral de Piedra Palustrine Wetland between July to October 2011. Where M: Migratory,

R, Resident, R,M: Resident and Migratory and R, M?: Resident and uncertain migratory birds (Obando-Calderón et al., 2015); G: Species distributed only in the Guanacaste area, P: Species distributed in Pacific slope; PC: Species distributed in Pacific and Caribbean slope; A: Species distributed in all Costa Rica; and PC: primary consumer, I-SC: invertebrate secondary consumer,

V-SC: vertebrate secondary consumer, TC: tertiary consumer (Stiles, 1985).

|

CUADRO 2 (Continuación) / TABLE 2 (Continued) |

|||||

|

Family |

Taxa |

English Name |

Status |

Distribution |

Trophic guild |

|

Family |

Taxa |

English Name |

Status |

Distribution |

Trophic guild |

|

Anatidae |

Dendrocygna autumnalis |

Black-bellied Whistling-Duck |

R |

A |

PC |

|

Cairina moschata |

Muscovy Duck |

R |

PC |

TC |

|

|

Anas discors |

Blue-winged Teal |

M |

A |

PC |

|

|

Cracidae |

Ortalis vetula |

Plain Chachalaca |

R |

G |

PC |

|

Odontophoridae |

Colinus cristatus |

Crested Bobwhite |

R |

P |

I-SC |

|

Columbidae |

Zenaida asiatica |

White-winged Dove |

R, M |

G |

PC |

|

Columbina inca |

Inca Dove |

R |

G |

PC |

|

|

Columbina passerina |

Common Ground-Dove |

R |

G |

PC |

|

|

Columbina talpacoti |

Ruddy Ground-Dove |

R |

PC |

PC |

|

|

Leptotila verreauxi |

White-tipped Dove |

R |

P |

PC |

|

|

Cuculidae |

Piaya cayana |

Squirrel Cuckoo |

R |

A |

V-SC |

|

Morococcyx erythropygius |

Lesser Ground-Cuckoo |

R |

G |

I-SC |

|

|

Crotophaga sulcirostris |

Groove-billed Ani |

R |

PC |

V-SC |

|

|

Caprimulgidae |

Nyctidromus albicollis |

Common Pauraque |

R |

P |

I-SC |

|

Trochilidae |

Chlorostilbon canivetii |

Canivet’s Emerald |

R |

G |

PC |

|

Amazilia rutila |

Cinnamon Hummingbird |

R |

G |

PC |

|

|

Rallidae |

Porphyrio martinica |

Purple Gallinule |

R |

A |

V-SC |

|

Aramidae |

Aramus guarauna |

Limpkin |

R |

A |

I-SC |

|

Burhinidae |

Burhinus bistriatus |

Double-striped Thick-Knee |

R |

G |

V-SC |

|

Jacanidae |

Jacana spinosa |

Northern Jacana |

R |

A |

V-SC |

|

Scolopacidae |

Actitis macularius |

Spotted Sandpiper |

M |

A |

I-SC |

|

Ciconiidae |

Mycteria americana |

Wood Stork |

R, M |

PC |

V-SC |

|

Jabiru mycteria |

Jabiru |

R |

G |

V-SC |

|

|

Anhingidae |

Anhinga anhinga |

Anhinga |

R |

A |

V-SC |

|

Ardeidae |

Tigrisoma mexicanum |

Bare-throated Tiger-Heron |

R |

PC |

V-SC |

|

Ardea herodias |

Great Blue Heron |

M |

A |

V-SC |

|

|

Ardea alba |

Great Egret |

R, M |

A |

V-SC |

|

|

Egretta thula |

Snowy Egret |

R, M |

A |

V-SC |

|

|

Egretta caerulea |

Little Blue Heron |

R, M |

A |

V-SC |

|

|

Egretta tricolor |

Tricolored Heron |

R, M |

A |

V-SC |

|

|

Bubulcus ibis |

Cattle Egret |

R, M |

A |

I-SC |

|

|

Butorides virescens |

Green Heron |

R, M |

A |

V-SC |

|

|

Nycticorax nycticorax |

Black-crowned Night-Heron |

R, M |

PC |

V-SC |

|

|

Nyctanassa violacea |

Yellow-crowned Night-Heron |

R, M |

PC |

V-SC |

|

|

Cochlearius cochlearius |

Boat-billed Heron |

R |

PC |

V-SC |

|

|

Threskiornithidae |

Eudocimus albus |

White Ibis |

R |

PC |

I-SC |

|

Platalea ajaja |

Roseate Spoonbill |

R |

PC |

V-SC |

|

|

Cathartidae |

Coragyps atratus |

Black Vulture |

R |

A |

V-SC |

|

Cathartes aura |

Turkey Vulture |

R, M |

A |

V-SC |

|

|

Pandionidae |

Pandion haliaetus |

Osprey |

M |

A |

V-SC |

|

Accipitridae |

Elanus leucurus |

White-tailed Kite |

R |

A |

V-SC |

|

Rostrhamus sociabilis |

Snail Kite |

R |

G |

I-SC |

|

|

Buteogallus anthracinus |

Common Black-Hawk |

R |

PC |

V-SC |

|

|

Rupornis magnirostris |

Roadside Hawk |

R |

A |

V-SC |

|

|

Parabuteo unicinctus |

Harris’s Hawk |

R, M? |

G |

V-SC |

|

|

Strigidae |

Lophostrix cristata |

Crested Owl |

R |

A |

V-SC |

|

Pulsatrix perspicillata |

Spectacled Owl |

R |

A |

V-SC |

|

|

Glaucidium brasilianum |

Ferruginous Pygmy-Owl |

R |

G |

V-SC |

|

|

Trogonidae |

Trogon melanocephalus |

Black-headed Trogon |

R |

G |

PC |

|

Momotidae |

Eumomota superciliosa |

Turquoise-browed Motmot |

R |

G |

V-SC |

|

Alcedinidae |

Megaceryle torquatus |

Ringed Kingfisher |

R |

A |

V-SC |

|

Bucconidae |

Notharchus hyperrhynchus |

White-necked Puffbird |

R |

PC |

V-SC |

|

Picidae |

Melanerpes hoffmannii |

Hoffmann’s Woodpecker |

R |

G |

I-SC |

|

Dryocopus lineatus |

Lineated Woodpecker |

R |

A |

I-SC |

|

|

Campephilus guatemalensis |

Pale-billed Woodpecker |

R |

A |

I-SC |

|

|

Falconidae |

Caracara cheriway |

Crested Caracara |

R |

P |

V-SC |

|

Herpetotheres cachinnans |

Laughing Falcon |

R |

PC |

V-SC |

|

|

Psittacidae |

Eupsittula canicularis |

Orange-fronted Parakeet |

R |

G |

PC |

|

Ara macao |

Scarlet Macaw |

R |

PC |

PC |

|

|

Amazona albifrons |

White-fronted Parrot |

R |

G |

PC |

|

|

Amazona autumnalis |

Red-lored Parrot |

R |

PC |

PC |

|

|

Amazona auropalliata |

Yellow-naped Parrot |

R |

G |

PC |

|

|

Furnariidae |

Lepidocolaptes souleyetii |

Streak-headed Woodcreeper |

R |

A |

I-SC |

|

Tyrannidae |

Attila spadiceus |

Bright-rumped Attila |

R |

A |

V-SC |

|

Myiarchus nuttingi |

Nutting’s Flycatcher |

R |

G |

I-SC |

|

|

Pitangus sulphuratus |

Great Kiskadee |

R |

A |

V-SC |

|

|

Megarhynchus pitangua |

Boat-billed Flycatcher |

R |

A |

I-SC |

|

|

Tyrannus melancholicus |

Tropical Kingbird |

R |

A |

PC |

|

|

Tityridae |

Pachyramphus aglaiae |

Rose-throated Becard |

R |

PC |

PC |

|

Corvidae |

Calocitta Formosa |

White-throated Magpie-Jay |

R |

G |

V-SC |

|

Troglodytidae |

Campylorhynchus rufinucha |

Rufous-naped Wren |

R |

G |

I-SC |

|

Thryophilus pleurostictus |

Banded Wren |

R |

G |

I-SC |

|

|

Turdidae |

Turdus grayi |

Clay-colored Thrush |

R |

A |

I-SC |

|

Parulidae |

Setophaga ruticilla |

American Redstart |

M |

A |

I-SC |

|

Setophaga petechia |

Yellow Warbler |

R, M |

A |

I-SC |

|

|

Basileuterus rufifrons |

Rufous-capped Warbler |

R |

P |

I-SC |

|

|

Thraupidae |

Sporophila corvina |

Variable Seedeater |

R |

PC |

PC |

|

Sporophila torqueola |

White-collared Seedeater |

R |

A |

PC |

|

|

Icteridae |

Agelaius phoeniceus |

Red-winged Blackbird |

R |

G |

I-SC |

|

Dives dives |

Melodious Blackbird |

R |

A |

I-SC |

|

|

Quiscalus mexicanus |

Great-tailed Grackle |

R |

A |

V-SC |

|

|

Icterus pustulatus |

Streak-backed Oriole |

R |

G |

I-SC |

|

|

Icterus pectoralis |

Spot-breasted Oriole |

R |

G |

I-SC |

|

Fig. 2. Distribution of trophic guilds by status in Corral de Piedra Palustrine Wetland between July to October 2011, where PC: primary consumer, I-SC: invertebrate secondary consumer, V-SC: vertebrate secondary consumer, (Stiles, 1985), M: Migratory, R, Resident, R, M: Resident and Migratory and R, M?: Resident and uncertain migratory birds (Obando-Calderón et al., 2015).

Fig. 3. Microhabitat use by birds in Corral de Piedra Palustrine Wetland between July to October 2011.

Fig. 4. Abundance observed of each point count at forest and open areas in Corral de Piedra Palustrine Wetland between July to October 2011.

Fig. 5. Rarefaction curve in the Corral de Piedra Palustrine Wetland between July to October 2011.