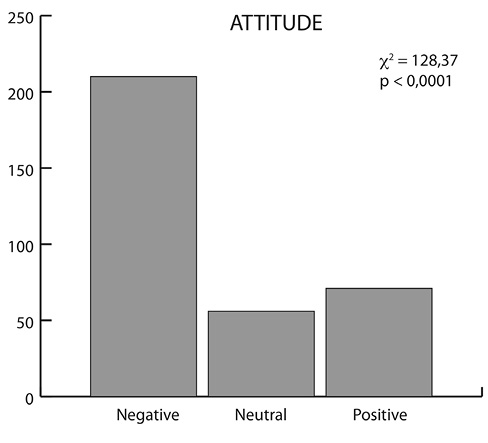

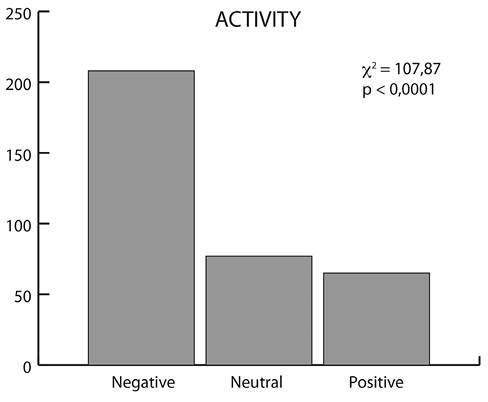

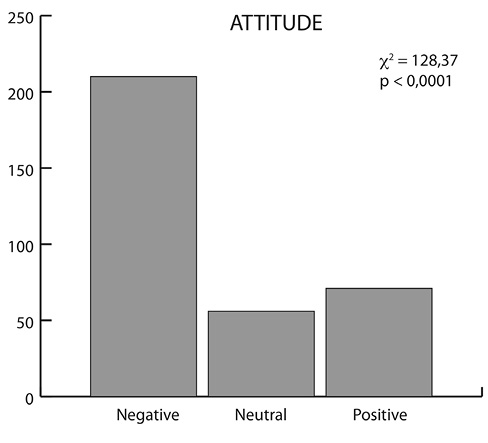

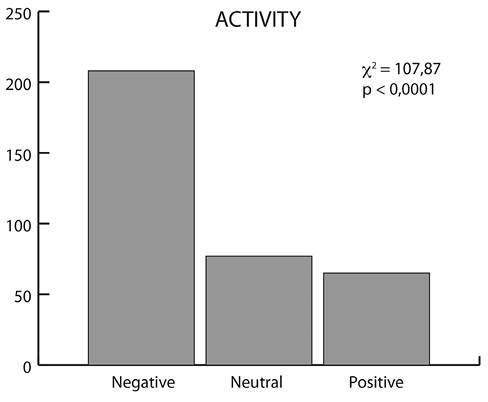

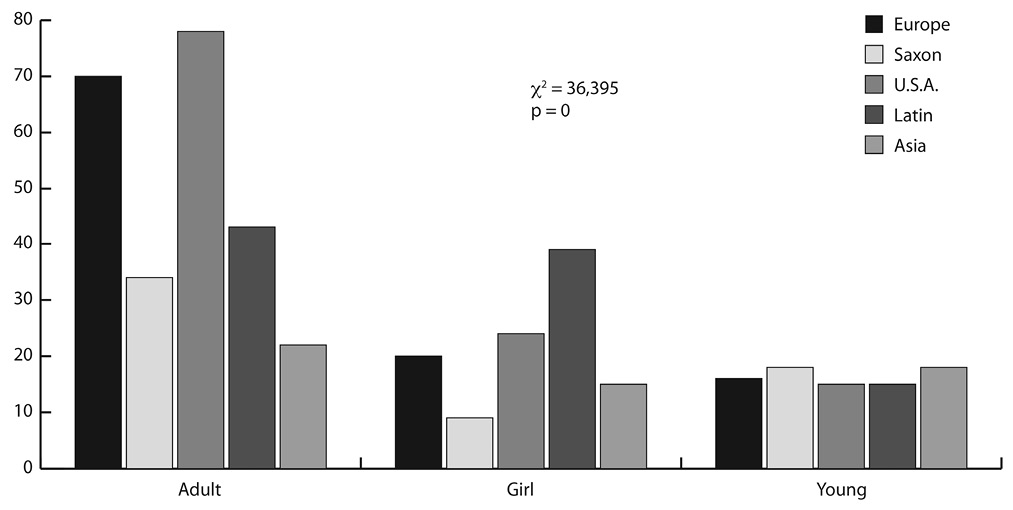

Fig. 1-2. Wolf’s attitude and activity in illustrations of Little Red Riding Hood in DeviantArt (2000-2015).

Role of gender, professional level, and geographic location of artists

on how they represent a story: the case of Little Red Riding Hood

Karina Barrientos1, Julián Monge-Nájera2, Zaidett Barrientos2 & María Isabel González Lutz3

1. Independent researcher, San José, Costa Rica, karinaestefmb@gmail.com

2. Laboratorio de Ecología Urbana, Vicerrectoría de Investigación, Universidad Estatal a Distancia, 2050 San José, Costa Rica.

3. Escuela de Estadística, Facultad de Ciencias Económicas, Universidad de Costa Rica, 2060 San José, Costa Rica.

Received 14-xii-2016 • Corrected 27-ii-2017 • Accepted 14-iii-2017

ABSTRACT: Little Red Riding Hood is a widely known classic story and its text has been abundantly analyzed, but no detailed statistical studies have been published about how it has been illustrated. We analyzed 554 images from the public artists’ site DeviantArt (January, 2015); classified them according to how the wolf, Little Red, and the environment were represented by the artists; and applied non-parametrical statistical tests to check several hypotheses. When compared with professionals, amateur artists tended to present a more neutral environment, and to humanize the wolf. Female artists were more likely to represent the wolf as a dressed man. Men were more likely to set the story outside of forests, to eroticize Red and to show her confused, scared or uninterested when first meeting the wolf. The neutral attitude of amateurs towards nature suggests indecision, while professional artists seem more used to produce family-friendly images. The female tendency to present the wolf as a man forces them to dress him and may reflect a stronger awareness about the moral of the story, meant to warn young women about men’s sexuality. Men deviate more from the forest setting because they feel safer in new environments, and also appear to see Red as a sexually attractive partner and the wolf as a competitor. Artists tended to show no sexual intent between the characters, but those who did were mostly amateurs. The global similarity in art about Little Red Riding Hood indicates that all modern audiences are familiar with the standard representation of the story in books, films and television. This article presents a rigorous quantitative approach to the study of art that can be applied to many other stories and subjects.

Key words: artistic interpretation, cultural differences, effect of gender on art, fairy tale representation.

Even though the origin of the Little Red Riding Hood story is obscure, according to Perrault’s 1697 version, a beautiful little girl is sent to visit her grandmother. On her way there, she speaks with a wolf and gives him directions to the woman’s house. When he arrives, he pretends to be Red to be allowed in and eats the grandmother; and then plays the same trick on Red and devours her as well. The story ends with a lesson for young, beautiful girls to stay away from the charming and handsome wolves, the most dangerous of all.

Although it is a well known story, it has in fact been adapted and readapted many times to teach the same lesson in different sociocultural contexts (Zipes, 1983). Tehrani (2013) applied biological software to some versions of the story and produced a similarity tree. Even though the effect of the missing versions, and of how well biological algorithms reflect cultural transmission, is unknown, the attempt is a valuable innovation in literary research.

The reasons for its creation, popularity, and the way the story affects its public have only began to be studied with some rigor, and traditional psychological interpretations have mostly been discarded by recent researchers. For example, children under five years of age are unable to understand the feelings of some characters (Bradmetz & Schneider, 1999); and Blecourt’s (2012) argued that printed versions, not oral versions, are the most influential. The role of such stories in societies has been discussed by recent authors like Sterck (2014) and Fazio, Brashier, Payne and Marsh (2015). A good case of adaptations that fulfill a social need are those by Spanish language writers, who presented Reds that live their sexual desires, reject maternal fears and fight the oligarchy (Vekić, 2009).

There are several well known interpretations of the meaning of the color red in the story, but they lack factual bases and ignore the fact the red cape was not part of the original story (Zipes, 1983). Another problem with ethnographic, sociological, anthropological, historical and psychological interpretations is that each ignores a wealth of data on the historical and geographic variants of the story, which is very old (Jones, 1987). This became more obvious with a recent reconstruction based on biological software (Tehrani, 2013).

Fairy tale illustrations affect how the characters are perceived (Mendoza & Reese, 2001) and in the case of Red, they have been even less studied than the story itself, and thus are in even more urgent need of analysis. The earliest attempt may have been that of Zipes (1983), who summarized his impressions of nearly 500 illustrations and concluded that the industrial production of books had homogenized the representation of Little Red Riding Hood as an un-erotic story of a disobedient girl who endangered herself and needed to be rescued by a man (the woodsman).

Beckett (2002) analyzed illustrations in more than 60 versions published before the year 2000 and found that the color red was key to story reinterpretations and that historically, illustrations reflected new audiences and new cultural contexts. A study published a few years later, based on how three artists interpreted the story, found a tendency to subvert and change the values of the original tale, by presenting Red as a transvestite, the wolf as a victim, and the grandma as a wearer of wolf furs (Bonner, 2005). Nevertheless, no statistical studies have been published for illustrations of the story along the line of Robinson and Wildermuth’s (2016) recent analysis of Cinderella.

In this article, we present a quantitative study of a large sample of illustrations and go beyond the method of Robinson and Wildermuth (2016) by using a list of hypotheses and non-parametric statistical tests to check the strength of those hypotheses.

METHODS

We extracted all images and associated data found with the search tool of devianart.com from the year 2000 to January, 2015. DeviantArt is an open web community where artists can post their work and interact with others with opinions and ideas; it has more than 200 million art pieces (Sartori et al., 2015).

We recorded artists’ declared sex, country and skill level (amateur or professional). Most use fictitious names so we do not have any reason to think that any significant number of users reported false sex or country data. We inserted the images into an Excel file and the main author (KB) classified them according to how the wolf, Little Red, and the environment were represented by the artists. Other characters like the grandmother, the mother, and the lumberjack were not included because they rarely appeared in the illustrations.

Attitude: Red’s and Wolf’s attitude were considered positive if they were smiling, or looked happy or otherwise pleased. They were considered negative if they were smirking, looked angry, confused, scared, doubtful, sexually aggressive, or something similar. When the face was not visible, or had no negative or positive expression, it was classified as neutral. The Environment was classified as positive when it was sunny, a forest with flowers and nice foliage, or similar. It was negative if it looked cold, dark, dangerous, unpleasant, or similar. When texts described one of them with praise, insults, etc. they were also used to decide if the overall representation was positive, negative or neutral.

Activity: Red’s activity was considered positive when she was acting friendly, enjoying candy, protecting nature and similar; negative when she was violent, deceitful, holding weapons, preparing poison, or similar. When she was just standing, sitting, walking or doing nothing in particular, her activity was considered neutral.

Representation: while classic artists normally represented the wolf as a wolf and Red as a girl, modern artists have explored many other options, in which –for example– the wolf is represented as a human, or Red as a boy, or the forest itself is a live animal. For this reason we also analyzed forest representation. Considering the sexual element that was there in the earlier known versions, we also recorded if Red or the wolf appeared nude, dressed, or partially dressed. Later, as recommended by one reviewer, we reanalyzed the images for sexual intent (see below).

Sexual intent among characters: This analysis classified the images according to whether Red, or the wolf, were shown to have a sexual interest in each other (defined by erotic kissing, facial expression, body contact and removal of clothing). We excluded from this category many illustrations that sexualized one or several characters, but did not show any sexual intent among characters.

Red was classified as child if she looked prepubescent, as young when she looked in her teens, and as adult otherwise.

The whole dataset, including original art and our ratings, is freely available for other researchers to corroborate and reanalyze (see additional files in the online edition of this journal).

We applied parametrical and non-parametrical statistical tests to check the following hypotheses:

1. Professional artists represent the wolf, Red, and the environment differently from amateurs (c2).

2. Female and male artists represent the wolf, Red, and the environment in different ways (c2).

3. Artists from different geographic regions differ in how they represent the wolf, Red, and the environment (ANOVA).

4. The use of color varies according to the gender of the artist (c2).

5. The minority of artists who sexualize Red are mostly amateurs (c2).

When there was no statistically significant difference between sexes, levels (amateur or professional), or geographic regions, they were merged and presented as single categories in the figures. When the difference was statistically significant, we included the contingency c2 results in the graph and the goodness of fit results in the text.

Data analyses were performed with the JMP statistical software package (SAS Institute Inc.; http://www.jmp.com/en_us/software/jmp.html). We used a 5% level of significance.

Ethics: We only used material that was publicly available, and do not include any information that identifies individual artists. We do not have any conflict of interest with the company Devianart.com

RESULTS

We analyzed 554 images and found that women and amateurs had similar results, so we checked the possibility that most women were amateurs, but it was not the case, so here we analyze them separately.

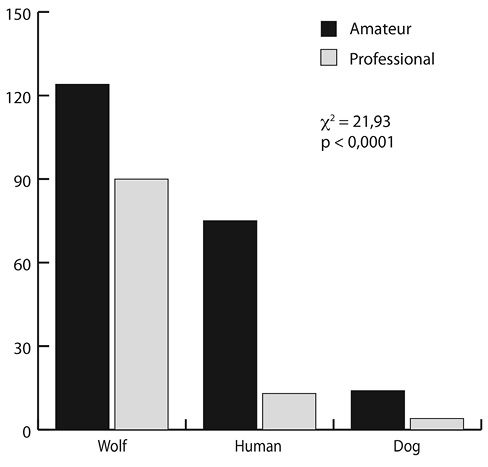

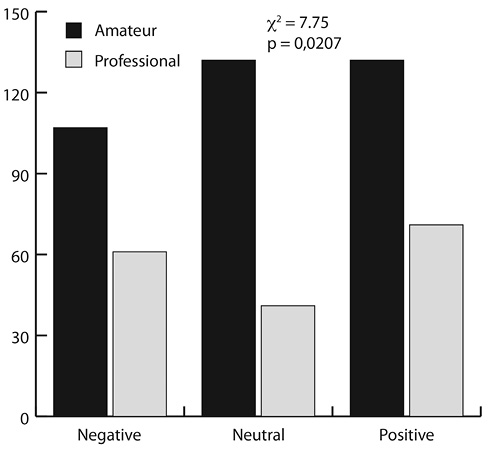

Most artists represented the wolf’s attitude (c2: 128,37; p<0,0001) and activity (c2: 107,87; p<0,0001) as negative (Fig. 1-2); and most painted the wolf as a wolf, but amateurs were more likely to optionally represent it as a human (c2: 77,82; p<0,0001) (Fig. 3).

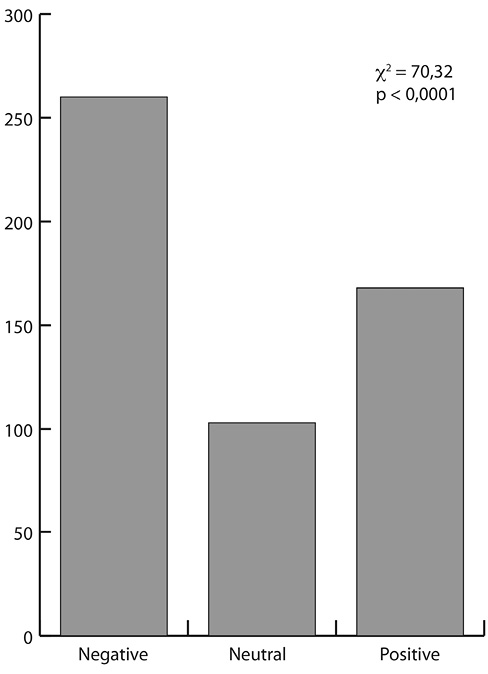

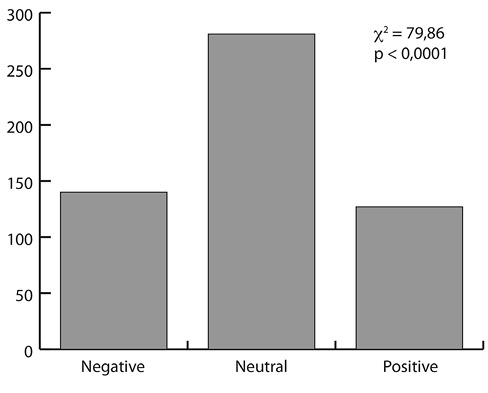

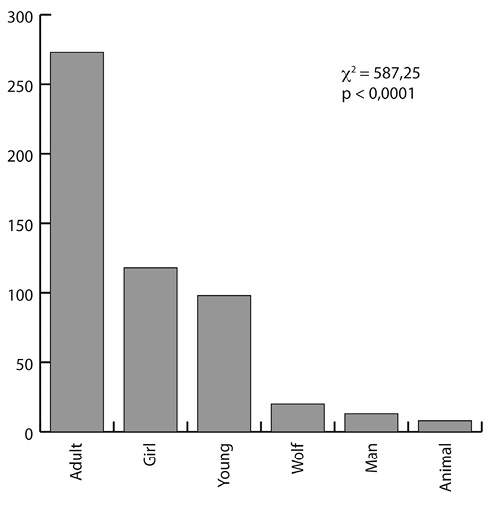

Both professionals and amateurs represented Red’s attitude mostly as negative (c2: 70,32; p<0,0001) (Fig. 4). Artists in general represented Red’s activity as neutral (c2: 79,86; p<0,0001) (Fig. 5). She was mostly represented as an adult woman, followed by representations as child or, less frequently, a young woman (c2: 587,25; p<0,0001) (Fig. 6).

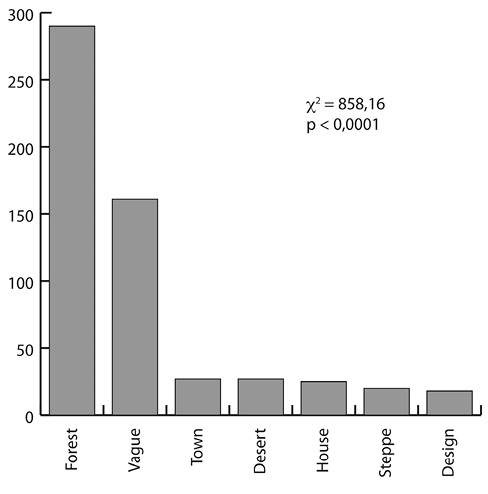

Professional artists represented the environment as positive (c2: 8,09; p<0,0175), while amateurs were equally divided among positive, negative and neutral (c2: 3,37; p<0,1854) (Fig. 7). Furthermore, the environment was not always represented as a forest, but that representation dominated (c2: 858,16; p<0,0001) (Fig. 8).

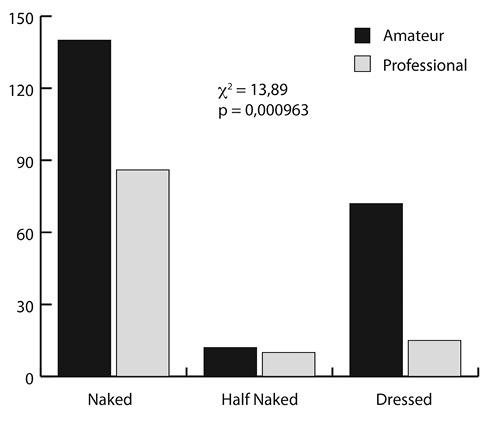

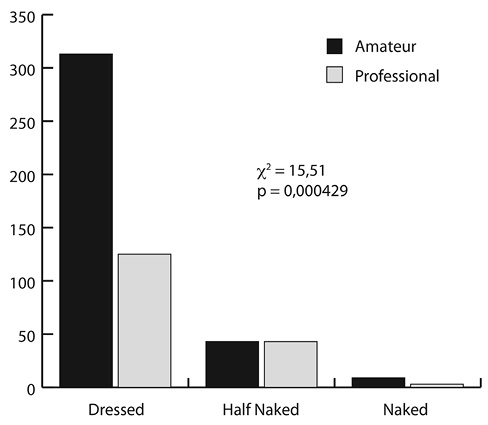

Both amateurs and professionals painted the wolf mostly without clothes (c2: 13,89; p<0,000963), but amateurs were more likely to dress him (c2: 109,86; p<0,0001) (Fig. 9). Both professionals and amateurs represented Red with her clothes on (c2: 15,51; p<0,0004), but amateurs dressed her in higher numbers (c2: 456,09; p<0,0001) (Fig. 10).

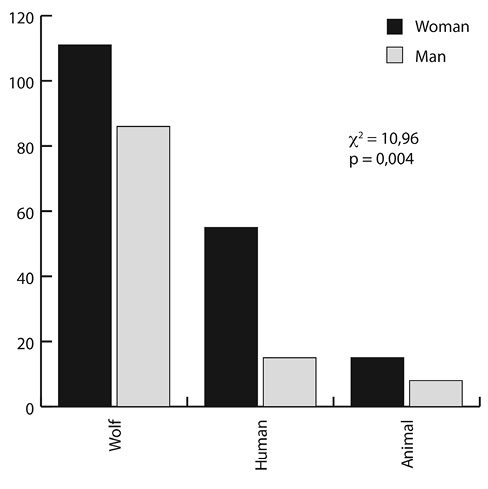

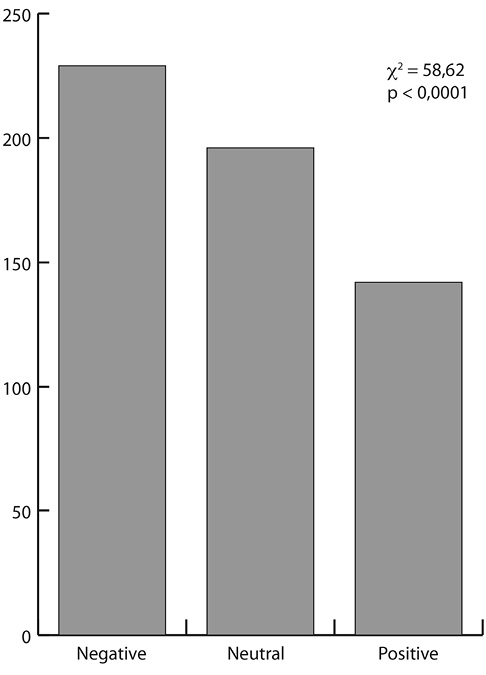

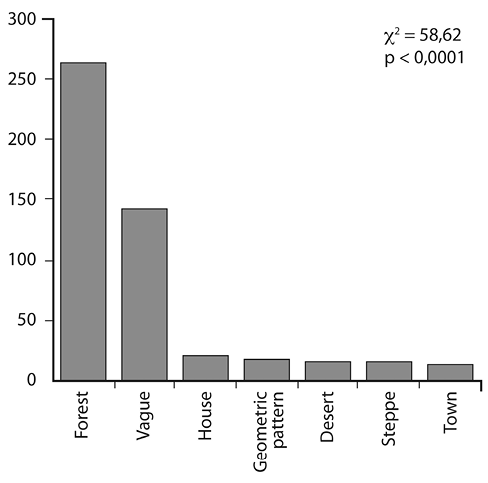

Both men and women represented the wolf as a wolf (c2: 10,96; p<0,0004), but women were more likely to present the wolf, as a second option, as a man (c2: 77,08; p<0,0001) (Fig. 11). In both cases the negative representation of Red’s attitude dominated (c2: 58,62; p<0,0001) (Fig. 12). Most artists represented the environment as a forest, with vague (i.e. unclear) environments being a second option (c2: 829,74; p<0,0001) (Fig. 13).

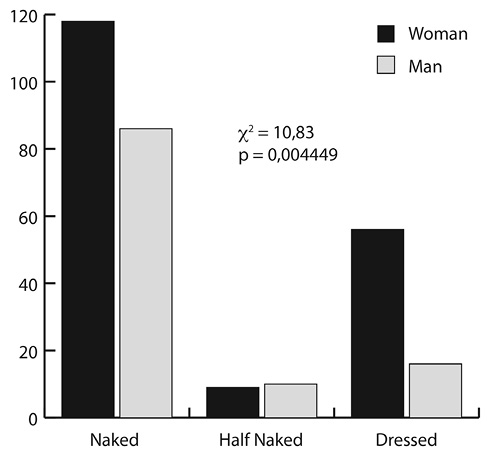

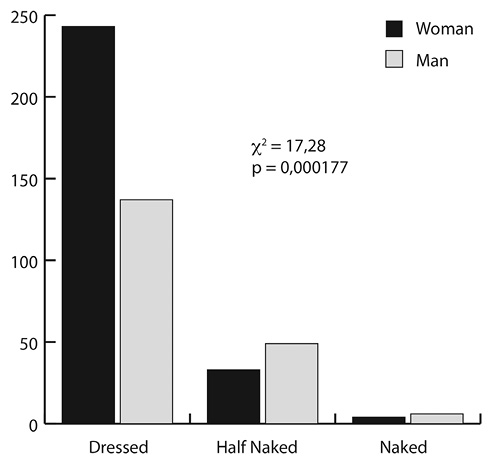

Both women and men painted Red mostly dressed (c2: 17,28; p<0,000177), but women had a higher proportion of dressed Reds (c2: 364,51; p<0,0001) and wolves (c2: 98; p<0,0001), although most artist had an undressed wolf (Fig. 14 and 15).

Red is represented mostly as an adult and girl is the second most common representation in most cultures (Fig. 16).

Independently of sex, training and nationality, warm and cold colors appeared in equal proportions in the paintings (i.e. 50/50).

Most artists illustrated the characters in a way that showed no sexual interest towards each other (c2:1359.34; p<0.0001). Nevertheless, those who show either Red or the wolf as rapists (26 out of 554), or showed both characters engaged willingly in sexual activities (16 out of 554), were mostly amateurs (c2=6,56; p= 0,0104).

DISCUSSION

When compared with professionals, amateur artists tended to present a more neutral environment, and to humanize the wolf. These results need an explanation but, in the absence of previous literature, we can only compare them with less directly related studies. The neutral attitude of amateurs towards nature, shown by the fact that they are less likely than professionals to paint the forest as a welcoming or as a menacing environment, indicates uncertainty. They do not seem to have made their minds either way; perhaps they have received less environmental education than professionals. A similar case was reported by Müller and Job (2009), who wrote that tourists had a neutral attitude towards the bark beetle if they knew little about the species, and a positive attitude if they had a better knowledge about it.

Although most artists showed no sexual intent in either the wolf or Red, a small number of them, who were mostly amateurs, did give the characters sexual interests in each other like in the original tale, as predicted by Zipes (2012).

The reason why amateurs humanize and sexualize the wolf more than professionals may have the same origin: in their daily work for companies, professional artists are under pressure to produce images that are acceptable to the general public. Amateurs, on the other hand, do not need to please customers and thus are freer to paint whatever comes to their minds. This can explain why they dare to venture farther from the accepted family-friendly version, as previously discussed by Zipes (1983), who proposed that the representation of Red as a bland, asexual character, arose with industrial book production. Free of such pressure, amateurs in our sample represented Red in the most varied conditions, from ghettos to futuristic cities, and the wolf as an attractive man, reflecting erotic interpretations always subjacent in this story (e.g. Hanks & Hanks, 1978; Zipes, 1983; Vekic, 2009) and in many others about women and animals (see Sterck, 2014, for aquatic animals; and Monge-Nájera, 2016, for the case of King Kong).

When compared with men, female artists were more likely to humanize and dress the wolf. Men, in turn, were more likely than women to present the story in non-forest settings; and to eroticize Red and show her confused, scared or uninterested in the wolf (quite in contrast with her reaction in the story). Why were there such marked gender differences?

The female tendency to present the wolf as a man probably made it necessary to dress him, because it seems natural and realistic to represent a wild animal without clothes and a man with them while moving through a forest, so these two characteristics are correlated. Furthermore, in comparison with men, women have a stronger social pressure to avoid public nudity and to avoid the implications that sexuality has for them (Berrington & Jones, 2002; Choi, Yoo, Reichert & LaTour, 2016). The fact that women are more likely to represent the wolf as a man may reflect a stronger awareness about the moral of the story, meant to warn women who reach reproductive age about men’s desires and seduction skills (Perrault, 1697).

The higher probability that male artists will paint an environment that is not the forest of the original story, may reflect the fact that men feel safer in new environments than women (Berrington & Jones, 2002). In comparison with women, men also represent Red’s first reaction to the wolf as negative and strongly eroticize her, and the possible reasons are multiple and also in need of further research, but the possibilities include that they fantasize with red as a sexually attractive partner and see the wolf as a competitor (Hanks & Hank, 1978; Zipes, 1983; Vekic, 2009; Monge-Nájera, 2016).

Finally, there were no geographic differences in any of the characteristics that we studied, possibly because, independently of where they are, media technology have familiarized all modern audiences with the standard representation of the story in books, films and television.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Melania Vargas, Silvia Ribera and Sergio Quesada for their assistance; Sergio Aguilar for the figures and Jack Zipes and one anonymous reviewer for valuable comments to improve the manuscript.

REFERENCES

Beckett, S. L. (2002). Recycling Red Riding Hood. NY: Routledge.

Berrington, E., & Jones, H. (2002). Reality vs. myth: Constructions of women’s insecurity. Feminist Media Studies, 2(3), 307-323. doi: 10.1080/1468077022000034817

Blecourt, W. de (2012). Tales of magic, tales in print. On the genealogy of fairy tales and the Brothers Grimm. Manchester U.

Bonner, S. (2006). “Visualizing Little Red Riding Hood.” Moveable Type: Journal of the Graduate Society. Department of English, University College London. Retrieved from https://www.ucl.ac.uk/moveable-type/pdfs/

2005-6/Bonner

Bradmetz, J., & Schneider, R. (1999). Is Little Red Riding Hood afraid of her grandmother? Cognitive vs. emotional response to a false belief. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 17, 501-514. doi: 10.1348/026151099165438

Choi, H., Yoo, K., Reichert, T., & LaTour, M. S. (2016). Do feminists still respond negatively to female nudity in advertising? Investigating the influence of feminist attitudes on reactions to sexual appeals. International Journal of Advertising, 35(5), 823-845

Dundes, Alan.(1989). Little Red Riding Hood; A Casebook. University of Wisconsin.

Fazio, L. K., Brashier, N. M., Payne, B. K., & Marsh, E. J. (2015). Knowledge does not protect against illusory truth. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 144(5), 993. doi: 10.1037/xge0000098

Hanks, C., & Hanks Jr, D. T. (1978). Perrault’s “Little Red Riding Hood”: Victim of the Revisers. Children’s Literature, 7(1), 68-77. doi: 10.1353/chl.0.0528

Jones, S. S. (1987). On Analyzing Fairy Tales: “Little Red Riding Hood” Revisited. Western Folklore, 46(2), 97-106. doi: 10.2307/1499927

Mendoza, J., & D. Reese. (2001). Examining Multicultural Picture Books for the Early Childhood Classroom: Possibilities and Pitfalls. Early Childhood Research and Practice, 3 (2), n2. Retrieved from http://ecrp.uiuc.edu/v3n2/

mendoza.html

Monge-Nájera, J. (2016). Ann´s secret relationship with King Kong: a biological look at Skull Island and the true nature of the Beauty and the Beast Myth. CoRis, 12, 13-28.

Müller, M., & Job, H. (2009). Managing natural disturbance in protected areas: tourists’ attitude towards the bark beetle in a German national park. Biological Conservation, 142(2), 375-383. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2008.10.037

Perrault, C. (1697). Les Contes de ma Mère l’Oye, Paris: Barbin.

Robinson, L. A. & Wildermuth, S. M. (2016). “It’s All About the Dress!”: An Examination of 150 Years of Cinderella Picture Book Covers. The Popular Culture Studies Journal, 4(1 -2), 4-40.

Sartori, A., Yanulevskaya, V., Salah, A. A., Uijlings, J., Bruni, E., & Sebe, N. (2015). Affective analysis of professional and amateur abstract paintings using statistical analysis and art theory. ACM Transactions on Interactive Intelligent Systems (TiiS), 5(2), 8. doi: 10.1145/2768209

Sterck, M. De. (2014). El despertar de la belleza. Sesenta cuentos populares de los cinco continentes. Madrid: Siruela.

Tehrani, J. J. (2013). The phylogeny of little red riding hood. PloS one, 8(11), e78871. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078871

Vekić, T. (2009). (Re)escrituras de Caperucita Roja en la literatura hispánica de la segunda mitad del siglo XX que desafían normas sociales coercitivas. Vancouver: University of British Columbia, M. Ars Thesis.

Zipes, J. (1983). The Trials and Tribulations of Little Red Riding Hood. South Handley, Mass.: Bergin & Garvey.

Zipes, J. (1993). A Second Gaze at Little Red Riding Hood’s Trials and Tribulations.” In Don’t Bet on the Prince: Contemporary Feminist Fairy Tales in North America & England, Ed. Jack Zipes. England: Scholar, 227-260. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/243762

Zipes, J. (2012). Fairy-Tale Collisions, or the Explosion of a GenreIn The Irresistible Fairy Tale: The Cultural and Social History of a Genre.Princeton University.

RESUMEN: Papel del género, nivel profesional y localización geográfica de los artistas sobre cómo representan una historia: el caso de Caperucita Roja. Caperucita Roja es una historia clásica muy conocida y su texto ha sido abundantemente analizado, pero no se han publicado estudios estadísticos detallados sobre cómo se ha ilustrado. Analizamos 554 imágenes del sitio DeviantArt.com (enero de 2015); clasificándolas de acuerdo a cómo representan los artistas al lobo, caperucita roja, y el ambiente. Aplicamos pruebas estadísticas no paramétricas para evaluar varias hipótesis. En comparación con los profesionales, los artistas aficionados tienden a presentar un ambiente más neutral, y a humanizar al lobo. Los hombres son más propensos a ubicar la historia fuera del bosque, a erotizar a caperucita; y mostrar su confusión, miedo o desinterés durante el primer encuentro con el lobo. La actitud neutral de los aficionados hacia la naturaleza sugiere indecisión, mientras que los profesionales producen imágenes dirigidas a toda la familia. La tendencia femenina a presentar al lobo como un hombre obliga a vestirlo y puede reflejar una mayor conciencia sobre la moral de la historia, destinada a advertir a las jóvenes sobre la sexualidad masculina. Los hombres se desvían más de la tradición del bosque porque se sienten más seguros en nuevos entornos; representan a caperucita como alguien sexualmente deseable, y ven al lobo como competidor sexual. En general se presenta poca intención sexual entre los personajes: quienes lo hacen son en su mayoría aficionados. La similitud internacional en el arte sobre caperucita indica que todas las audiencias modernas están familiarizadas con la representación estándar de la historia en libros, películas y televisión. Este artículo presenta un riguroso enfoque cuantitativo al estudio del arte, que se puede aplicar a muchas otras historias y temas.

Palabras clave: interpretación artística, diferencias culturales, efecto del género en el arte, representación de cuento de hadas.

Fig. 1-2. Wolf’s attitude and activity in illustrations of Little Red Riding Hood in DeviantArt (2000-2015).

Fig. 3. Wolf’s representation in illustrations of Little Red Riding Hood in DeviantArt (2000-2015).

Fig. 4. Red’s attitude in illustrations of Little Red Riding Hood in DeviantArt (2000-2015) according to amateurs and professionals.

Fig. 5. Red’s activity in illustrations of Little Red Riding Hood in DeviantArt (2000-2015).

Fig. 6. Red’s representation in illustrations of Little Red Riding Hood in DeviantArt (2000-2015).

Fig. 7. Environment in illustrations of Little Red Riding Hood in DeviantArt (2000-2015) according to amateurs and professionals.

Fig. 8. Environment’s representation in illustrations of Little Red Riding Hood in DeviantArt (2000-2015).

Fig. 9. Wolf’s clothing in illustrations of Little Red Riding Hood in DeviantArt (2000-2015) according to amateurs and professionals.

Fig. 10. Red’s clothing in illustrations of Little Red Riding Hood in DeviantArt (2000-2015) according to amateurs and professionals.

Fig. 11. Wolf’s representation in illustrations of Little Red Riding Hood in DeviantArt (2000-2015) according to the artist’s gender.

Fig. 12. Red’s attitude in illustrations of Little Red Riding Hood in DeviantArt (2000-2015).

Fig. 13. Environment’s representation in illustrations of Little Red Riding Hood in DeviantArt (2000-2015).

Fig. 14. Wolf’s clothing in illustrations of Little Red Riding Hood in DeviantArt (2000-2015) according to the artist’s gender.

Fig. 16. Red’s representation in illustrations of Little Red Riding Hood in DeviantArt (2000-2015) according to the artist’s cultural origin. Saxon means United Kingdom and former colonies of dominant Anglo-Saxon culture (Australia, New Zealand, etc.).

Fig. 15. Red’s clothing in illustrations of Little Red Riding Hood in DeviantArt (2000-2015) according to the artist’s gender.