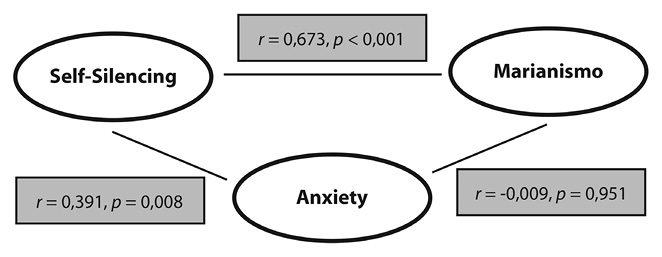

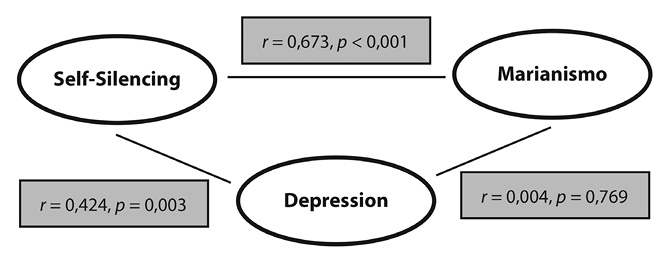

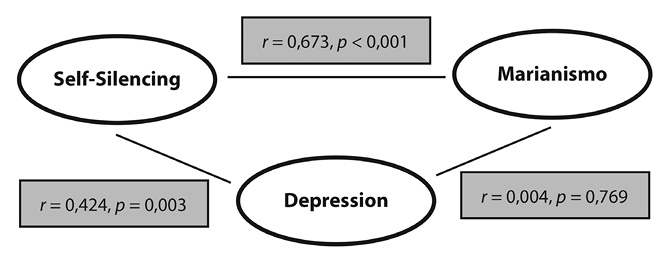

Fig. 1. Correlation coefficients among test variables.

Marianismo Identity, Self-Silencing, Depression and Anxiety

in Women from Santa María de Dota, Costa Rica

Mia Kosmicki

Knox College, 2 E. South Street, Galesburg, IL; mtkosmicki@knox.edu

Received 01-Xi-2016 • Corrected 25-ii-2017 • Accepted 01-iii-2017

ABSTRACT: “Marianismo”, a gender role script in Latin America, is the concept that women should be the spiritual family leaders, remain abstinent until marriage, and be submissive to their husbands; it originates from the Catholic Church’s image of the Virgin Mary. I examined the link between Marianismo identity, self-silencing, depression and anxiety in a sample of 47 women from the town of Santa Maria de Dota, Costa Rica, who completed self-report scales. I found positive correlations between Marianismo identity and self-silencing, and between self-silencing and both anxiety and depression. Older women rated higher in Marianismo and self-silencing.

Key words: marianismo; gender roles; depression; anxiety; self-silencing; submissive.

Worldwide statistics on mental illness demonstrate that women experience depression at almost twice the rate of men (World Health Organization [WHO], 2016). Women also experience anxiety, psychological distress, sexual violence, domestic violence and escalating rates of substance use at higher rates than men across all countries and settings (WHO, 2016). Understanding the underlying causes of these discrepancies is key in the reduction of mental illness in women, and in turn, the reduction of mental illness in the general population. There is strong support for a link between experiences with gender inequality and conformity to gender roles and higher rates of depression and anxiety in women (eg., Klonoff et al., 2000; Moradi & Funderburk, 2006; Fischer & Holz, 2007).

Specifically, studies conducted with Mexican-Americans have demonstrated a link between “Marianismo” or the expected gender script of women in Latin America, and high rates of depression and anxiety (eg. Castillo, Perez, Castillo, & Ghosheh, 2010; Nuñez et al., 2015). The practice of self-silencing to maintain harmony in relationships, an important quality of marianismo, has also been shown to be a factor in rates of depression and anxiety among populations in the United States (eg. Gratch, Bassett, & Attra, 1995; Cramer, Gallant, & Langois, 2005; Hurst & Beesley, 2012). However, to my knowledge, there has not been a study conducted focusing on the mental health and rates of psychological distress of women in Costa Rica. I hope to lessen this gap in knowledge by exploring the roles of self-silencing and strong identification with Marianismo values with regards to increased rates of depression and anxiety among Costa Rican women.

Culture plays an important role in shaping one’s identity, and therefore must be considered when studying gender roles and their effects on mental health (Castillo et al., 2010). For example, in Latin American countries, gender roles for men and women differ from those in the United States. Female gender roles in Latin American are clearly defined by the concept of “Marianismo” (Castillo et al., 2010). The term was first coined by Evelyn Stevens in 1973 to describe women’s subordinate position in Latin American society and to bring attention to the unrealistic and idealized gender-role expectations of women (Stevens, 1973). Some characteristics of Marianismo include remaining virtuous, humble, and spiritually superior to men (Castillo et al., 2010). The main values of Marianismo are centered around the concepts of “familismo” (a woman should be a good wife, mother, and caretaker), “respeto” (a woman should be modest in behavior, not talk about sex, and not engage in sex for pleasure), and “simpática” (a woman should avoid conflicts at all costs and silence the self if necessary to maintain harmony) (Castillo et al., 2010). The concept of Marianimso is derived from the image of the Virgin Mary: virginally pure, non-sexual, and self-sacrificing (Castillo & Cano, 2007).

Female gender roles have been linked to a number of negative health outcomes in populations across the United States. For instance, various studies have demonstrated a strong link between experiences of sexism and gender inequality and rates of psychological distress, including symptoms of depression and anxiety (eg., Klonoff et al., 2000; Moradi & Funderburk, 2006; Fischer & Holz, 2007). Specifically, the adherence to strict, traditional gender roles has been shown to play a role in symptomology among women (Sweeting, Bhaskar, Benzeval, Popham, & Hunt, 2013). Sweeting et al. (2013) also found that as gender roles and gender role beliefs become more egalitarian between males and females, the excessive prevalence of major depressive disorder in females decreases. This suggests increased equality, or perceived equality, between males and females could help improve major depressive disorder in particularly afflicted communities of women. Although some studies conducted with populations from Latin American have found links between a strong Marianismo identity and factors such as sexual health, domestic violence, anxiety and depression (Castillo et al., 2010; Nuñez, 2015), the literature is scarce. For this reason, Marianismo is an important factor to include in studies on mental health of Latin American women.

One component of Marianismo which has individually been linked with higher rates of anxiety and depression in women is the practice of self-silencing. Self-silencing refers to withholding parts of the self from expression, such as opinions and emotions, to maintain a relationship (Jack, 1999). Self-silencing is theorized to be motivated by cultural imperatives which outline what it means to be a “good woman” (Jack, 1999). Although self-silencing maintains harmony in a relationship, the accompanying “loss-of-self” is shown to be linked with higher rates of psychological distress among college-age participants (eg., Gratch, 1995; Cramer et al., 2005; Hurst & Beesley, 2012). Hurst and Beesley (2012) also found that the practice of self-silencing significantly mediates the relationship between experiences with sexism and rates of depression and other forms of psychological distress. This suggests that voicing one’s opinions and feelings could act as a buffer against the harmful effects of sexist experiences. Cramer et al., 2005 found that individuals, males and females, who self-reported having more masculine traits were less likely to self-silence, and less likely to experience depression, suggesting that gender roles play a significant part in the relationship between self-silencing and depression. Self-silencing is a key component of Marianismo which could significantly explain the relationship between Marianismo and higher rates of depression and anxiety.

The current study seeks to explore the gaps in knowledge about the links between marianismo, self-silencing, and high rates of depression and anxiety among women. To my knowledge, no study has been conducted with women from Costa Rica and, because culture plays such a strong role in gender formation, it is impossible to generalize studies done with other populations of women to all women in Latin America. Each country is distinct, and I seek to understand how gender roles affect mental health specifically among adult females in Costa Rica. Although the results could not be generalized to every other population of women, it could set a foundation for research in the future, which could have implications for the improvement of women’s mental health worldwide. Before we are able to treat mental illnesses across the world we must first understand the underlying causes of these problems. There exists large gaps in knowledge as to why women are more prone to mental illnesses such as depression and anxiety. My research hopes to make this gap just a bit smaller by shedding light on possible causes of psychological distress among women.

METHODS

Participants: 47 women from the town of Santa María de Dota. The ages of the women ranged from 18 to 79 years of age (M = 44,65, SD = 16,3). Participants were found through attending various women’s groups in the town and through communication with contacts in the area. Of the 47 women, 8 are in free unions (17%), 18 are married (38,3), 14 are single (29,8%), 3 are divorced (6,4%), and 4 are widowed (8,5%). Most the participants (70,2%) reported that they actively practice their religion. 57,4% of women reported that they work in home as “amas de casa”.

Measures: Marianismo Beliefs Scale (MBS; Castillo et al., 2010) is a 24-item scale which asks respondents to rate the extent to which they agree with statements regarding the female gender role values and practices ascribed to the multidimensional construct of marianismo on a 4-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). The MBS consists of five subscales: Family Pillar (Latinas are the main source of strength for the family), Virtuous and Chaste (Latinas should be morally pure in thought and sexuality), Subordinate to Others (Latinas should show respect and obedience to men), Silencing Self to Maintain Harmony (Latinas should not share personal thoughts or needs in order to maintain harmony in the relationship with male partner), and Spiritual Pillar (Latinas are the spiritual leaders of the family and are responsible for the family’s spiritual growth). Higher scores on each subscale indicate greater endorsement of marianismo beliefs.

The Silencing the Self Scale (STSS: Jack & Dill, 1992) is a 31-item self-report scale designed to measure behavior in and beliefs about partner relationships. Participants respond on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree, with higher scores indicating greater self-silencing. Items reflect four rationally derived subscales: Silencing the Self (e.g., “I don’t speak my feelings in an intimate relationship when I know that they will cause disagreement”), Externalized Self-Perception (e.g., “I tend to judge myself by how other people see me”), Divided Self (e.g., “Often I look happy enough on the outside, but inwardly I feel angry and rebellious”), and Care as Self-Sacrifice (e.g., “Caring means putting the other person’s needs in front of my own”).

Personality Assessment Inventory (PAI: Morey, 2007) is a self-report 344-item personality test that assesses a respondent’s personality and psychopathology. Two subsets of the PAI were used to assess levels of anxiety of depression: the ANX (anxiety subset) and the DEP (depression). The ANX scale consists of three subscales measuring three primary components of anxiety: Cognitive (ANX-C), which taps ruminative worry and cognitive beliefs; Affective (ANX-A), to measure feelings of tension, panic, and nervousness; and Physiological (ANX-P) to measure the somatic features of anxiety, such as racing heart and shallow breathing. The DEP scale measures three major components of depression: Cognitive (DEP-C) to measure negative expectancies, helplessness, and cognitive errors. Affective (DEP-A) to measure unhappiness, dysphoria, and apathy; and Physiological (DEP-P) to measure vegetative and somatic features of depression. They each consist of 24 items, with several reverse-scored items in each scale.

The forms appear in Digital Appendix 1.

Procedure: The women wished to participate in a group setting, so workshops were held in an event center. The number of women who attended each session varied from three to eleven. Following a brief introduction of the investigator and the study, the women read and signed the informed consent form. Then, each woman filled out a form with various demographic questions including their age, civil status, occupation, and whether or not they regularly practiced their religion. Next, a series of four scales were administered, one for each of the variables. The women took the scales one at a time, asking questions and discussing the items on the scales amongst themselves. It took each women anywhere from fifteen minutes to an hour to complete all of the scales. Afterwards, the participants talked and asked questions for an additional half hour. The investigator asked the women how they were and made sure no one left experiencing psychological distress over the personal nature of the questions.

RESULTS

Table 1 shows the ranges, minimums, maximums, means, and standard deviations for all four principle test variables. Marianismo was shown to be significantly positively correlated with Self-Silencing (r=0,673, p<0,001). Self-Silencing was shown to be significantly positively correlated with both depression (r=0,424, p=0,003) and anxiety (r=0,391, p=0,008), however Marianismo was not found to be significantly correlated with depression or anxiety. Figure 1 and 2 represent the correlation coefficients between the principle variables. Depression and anxiety are also significantly correlated with one another (r=0,664, p<0,001). This is not surprising due to the high rates of comorbidity of depression and anxiety. Some studies report that anxiety and depression are comorbid in more than half of all patients with either disorder (Hirschfeld, 2001; Cameron, 2007). An increase in age of the participants was associated with an increase in both Marianismo beliefs (r=0,511, p<0,001) and self-silencing (r=0,555, p<0,001).

DISCUSSION

The relationship between older age groups and higher gender role traditionalism has been previously supported (Sweeting et al., 2013), but the connection between age and self-silencing is not as well established, and could have many implications for future studies. The correlation between self-silencing and depression and anxiety could account for a portion of the discrepancy in rates of depression and anxiety between men and women, with the rate of women being twice that of men across the lifetime (Kessler et al., 1994, 1995; Weissman et al., 1994, 1996; Gater et al., 1998). Self-silencing has been constructed around social and cultural mandates which encourage women to put others first, and silence themselves when necessary to maintain harmony (Jack, 1991). The fact that this practice has been correlated with negative health outcomes across various countries and settings is alarming. Further examination of the components of self-silencing could help to reveal which parts are linked to depression and anxiety, and understand what could be done to help women who practice self-silencing in all parts of the world.

Marianismo being highly significantly correlated with the practice of self-silencing demonstrates the power of cultural messages women receive about how to be a “good woman”. Marianismo is deeply embedded in Latin American culture and gender roles are a basic organizing feature in Latina/o families (Cauce & Domenech-Rodriguez, 2002). There are many positive components of Marianismo, such as being the spiritual leader of the family, but the fact that it is associated with the practice of self-silencing, which is linked to some negative health outcomes, raises alarm regarding the construction of gender roles. Piña-Watson, Castillo, Jung, Ojeda, and Castillo-Reyes (2014) note that despite growing research on suicidality, depression, and well-being in Latino/a youth, gender roles have been largely overlooked as a contributing factor. They emphasize the importance of considering gender socialization in future studies with Latino/a populations.

There are many possible explanations for the lack of significance in the correlation between Marianismo and either depression or anxiety, despite both variables being significantly correlated with self-silencing. One explanation is that some components Marianismo are associated with increases in depression and anxiety, while other components have a positive or null effect on mental health. For instance, one study differentiated between “positive Marianismo” and “negative Marianimso” by examining the outcomes of high scores on each of the subscales. They found that the family and spiritual pillars were related to higher grades and academic motivation, while subordination and self-silencing were negatively correlated with academic performance (Piña-Watson, Lorenzo-Blanco, Dornhecker, Martinez, & Nagoshi, 2016). It would be important for future studies to consider the components of Marianismo independently as “positive” and “negative” factors on mental health.

The group setting seemed to be a positive accommodation for most women. It provided a sense of social support, and allowed the women to talk freely amongst themselves and led to several interesting debates and conversations. However, despite the numerous benefits of the group setting, it also had its setbacks. In group settings, pressure to conform to the rest of the group and a phenomenon known as “group polarization” can occur. Group polarization is the tendency a group of already like-minded people to become more extreme in their beliefs post-discussion (Stoner, 1961, 1968). Women may have also changed their original responses to be more in line with the group consensus because of the powerful pressure to conform in groups as demonstrated by Asch (1956) using the famous line judgement task. Despite the possibility of group influence, each woman had unique combination of responses, demonstrating a good degree of independent thought.

This study had many limitations. The group setting was both a limitation and an advantage for the reasons listed. Other limitations include the small sample size, the short amount of time allotted to find participants and collect the surveys, and the low generalizability to other populations of women due to the homogeneity of the group. A larger sample size with women from different parts of Costa Rica would increase the possibility of generalizability to other populations of women in Latin America. Another limitation is the tendency for people to give socially favorable responses to items in scales (Tourangeau & Rasinski, 1988). The women may not have wanted to appear to defy traditional gender roles for women as they are a strong part of cultural identity. In addition, women may not have been completely forthcoming about their symptoms of depression and anxiety due to the stigma of mental illness. Despite these limitations, the study conducted has scientific, cultural, and social value. It helps to explain and understand the underlying reasons for the high rates of depression and anxiety among women and opens the door to similar studies with varied populations in the future.

The current study has many implications for research in the future. Other populations of women in other regions (the city, as opposed to a small town) could yield much different results due to differing processes of gender role socialization. Due to the lack of a significant correlation between Marianismo, depression, and anxiety, as demonstrated in other populations, it is possible that being a part of a social group acts as a buffer against the harmful effects of traditional gender role beliefs. It would be interesting to see if social group membership impacts the relationship between Marianismo identity and depression and anxiety. Past studies have shown that social support is one of the most important determinants of physical and mental health (House, Landis, & Umberson, 1988; Wilkinson & Marmot, 2003). The study could also be improved by finding a way to control the effect of group influence. This could be done by telling the women to complete the surveys silently and then to have a time at the end to discuss the questions and responses. Also, as mentioned above, further examination of the subscales of both Marianismo and self-silencing could further explain the correlations between these variables and negative mental health outcomes. A more extensive study into the particularities of these concepts could shed light onto the problem of mental illness in women across the world.

REFERENCES

Asch, S. E. (1956). Studies of independence and conformity: I. A minority of one against a unanimous majority. Psychological monographs: General and applied, 70(9), 1. doi: 10.1037/h0093718

Castillo, L. G., Perez, F. V., Castillo, R., & Ghosheh, M. R. (2010). Construction and initial validation of the Marianismo Beliefs Scale. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 23,163-175. doi:10.1080/09515071003776036

Cameron, O. G. (2007). Understanding Comorbid Depression and Anxiety. Psychiatric Times, 24(14), 51-51. Retrieved from http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/articles/understanding-comorbid-depression-and-anxiety.

Cauce, A. M., & Domenech-Rodríguez, M. (2002). Latino families: Myths and realities. In J. M. Contreras, K. A. Kerns, A. M. Neal-Barnett, J. M. Contreras, K. A. Kerns, & A. M. Neal-Barnett (Eds.), Latino children and families in the United States: Current research and future directions (pp. 3-25). Westport, CT, US: Praeger Publishers/Greenwood Publishing Group.

Cramer, K. M., Gallant, M. D., & Langois, M. W. (2005). Self-silencing and depression in women and men: Comparative structural equation models. Personality and Individual Differences, 39,581–592. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2005.02.012

Fischer, A. R., & Holz, K. B. (2007). Perceived discrimination and women’s psychological distress: The roles of collective and personal self-esteem. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 54, 154–164.

doi:10.1037/0022-0167.54.2.154

Gater, R., Tansella, M., Korten, A., Tiemans, B., Mavreas, V., & Olatawura, M. (1998). Sex differences in the prevalence and detection of depressive and anxiety disorders in general health care settings: report from the World Health Organization Collaborative Study on Psychological Problems in General Health Care. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry, 55, 405–413. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.5.405

Gratch, L. V., Bassett, M. E., & Attra, S. L. (1995). The relationship of gender and ethnicity to self- silencing and depression among college students. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 19, 509–515. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.1995.tb00089.x

Hirschfeld, R. M. A. (2001). The Comorbidity of Major Depression and Anxiety Disorders: Recognition and Management in Primary Care. Primary Care Companion to The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 3(6), 244–254. doi:10.4088/PCC.v03n0609

House, J. S., & Landis, K. R., Umberson, D. (1988). Social relationships and health. Science, 241(4865), 540. doi:10.1126/science.3399889

Hurst, R. J., & Beesely, D. (2012). Perceived Sexism, Self-Silencing, and Psychological Distress in College Women. Sex Roles, 68, 311-320. doi: 10.1007/s11199-012-0253-0

Jack, D. C. (1999). Silencing the self: Inner dialogues and outer realities. In T. Joiner & J. C. Coyne (Eds.), The interactional nature of depression (pp. 221–246). Washington: American Psychological Association. doi:10.1037/10311-008

Kessler, R. C., McGonagle, K. A., Zhao, S., Nelson, C. B., Hughes, M., Eshleman, S., & Kendler, K. S. (1994). Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III—R psychiatric disorders in the United States: Results from the National Comorbidity Study. Archives of General Psychiatry, 51(1), 8-19. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002

Kessler, R., Sonnega, A., Bromet, E., Hughes, M., & Nelson, C. (1995). Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry, 52, 1048–1060. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950240066012

Klonoff, E. A., Landrine, H., & Campbell, R. (2000). Sexist discrimination may account forwell-known gender differences in psychiatric symptoms. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 24, 93–99. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.2000.tb01025.x.

Moradi, B., & Funderburk, J. R. (2006). Roles of perceived sexist events and perceived social support in the mental health of women seeking counseling. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53, 464–473. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.53.4.464.

Nuñez, A., González, P., Talavera, G. A., Sanchez-Johnsen, L., Roesch, S. C., Davis, S. M., Arguelles, W., Womack, V. Y., Ostrovsky, N. W., Ojeda, L., Penedo, F. J., & Gallo, L. C. (2015). Machismo, Marianismo, and Negative Cognitive-Emotional Factors: Findings from the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos Sociocultural Ancillary Study. Journal of Latina/o Psychology, 4(4), 202.

Piña-Watson, B., Castillo, L. G., Ojeda, L., Rodriguez, K. M. (2013). Parent Conflict as a Mediator Between Marianismo Beliefs and Depressive Symptoms for Mexican American College Women. Journal of American College Health, 61(8), 491-496. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2013.838567

Piña-Watson, B., Castillo, L. G., Jung, E., Ojeda, L., Castillo-Reyes, R. (2014). The Marianismo Beliefs Scale: Validation with Mexican American Adolescent Girls and Boys. Journal of Latina/o Psychology, 2, 113-130. doi:10.1037/lat0000017

Piña-Watson, B., Lorenzo-Blanco, E. I., Dornhecker, M., Martinez, A. J., & Nagoshi, J. L. (2016). Moving away from a cultural deficit to a holistic perspective: Traditional gender role values, academic attitudes, and educational goals for Mexican descent adolescents. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 63, 307-318. doi:10.1037/cou0000133

Stevens, E. P. (1973). Marianismo: The other face of machismo in Latin America. In A. Pescatello (Ed.), Female and male in Latin America (pp. 89–101). Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press.

Stoner, J. A. F. (1961). A comparison of individual and group decisions involving risk. Master’s thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA.

Stoner, J. A. F. (1968). Risky and cautious shifts in group decisions: The influence of widely held values. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 4, 442–459. doi:10.1016/0022-1031(68)90069-3

Sweeting, H., Bhaskar, A., Benzeval, M., Popham, F., & Hunt, K. (2014). Changing gender roles and attitudes and their implications for well-being around the new millennium. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 49, 791-809. doi:10.1007/s00127-013-0730-y

Tourangeau, R., & Rasinski, K. A. (1988). Cognitive Processes Underlying Context Effects in Attitude Measurement. Psychological Bulletin, 103, 299–314. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.299

Weissman, M., Bland, R., Canino, C., Faravelli, C., Greenwald, S., Hwu, H., Joyce, P., Karam, E., Lee, C., Lellouch, J., Lépine, J., Newman, S., Rubio-Stipec, M., Wells, J., Wickramaratne, P., Wittchen, H., & Yeh, E. (1996). Cross-national epidemiology of major depression and bipolar disorder. Journal of the American Medical Association, 276, 293–299. doi: 10.1001/jama.1996.03540040037030

Weisman, M. M., Bland, R. C., Canino, G. J., Greenwald, S., Hwu, H. G., Lee, C. K., ... & Wittchen, H. U. (1994). The cross national epidemiology of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Journal of clinical Psychiatry, 55(3 Suppl.), 5-10.

Wilkinson, R, & Marmot, M. (2003). The social determinants of health. The solid facts. Copenhaguen: WHO Regional Office for Europe.

World Health Organization (WHO). (2016). Gender and women’s mental health. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/mental_health/prevention/genderwomen/en/

RESUMEN: Marianismo, auto-silenciamiento, depresión y ansiedad en mujeres de Santa María de Dota, Costa Rica. El “marianismo”, una imagen de género propia de América Latina, es el concepto de que las mujeres deben ser líderes espirituales de la familia, permanecer en abstinencia sexual hasta el matrimonio y ser sumisas a sus maridos; se origina de la imagen de la Virgen María según la Iglesia Católica. Examiné el vínculo entre la identidad marianista, el auto-silenciamiento, la depresión y la ansiedad en una muestra de 47 mujeres del poblado de Santa María de Dota, Costa Rica, quienes llenaron formularios de auto-evaluación. Encontré correlaciones positivas entre la identidad marianista y el auto-silenciamiento, y entre el auto-silenciamiento, la ansiedad y la depresión. Las mujeres de mayor edad calificaron más alto en marianismo y auto-silenciamiento.

Palabras clave: marianismo; rol de género; depresión; ansiedad; auto-silenciamiento; sumisión.

TABLE 1

Means, ranges, minimums, maximums, and standard deviations for test variables

|

N |

Range |

Minimum |

Maximum |

Mean |

Std. Deviation |

|

|

Marianismo |

47 |

2,65 |

1,18 |

3,83 |

2,59 |

0,54 |

|

Self-Silencing |

46 |

95 |

33 |

128 |

77,76 |

20,28 |

|

Depression |

47 |

47 |

28 |

75 |

46,28 |

12,64 |

|

Anxiety |

46 |

55 |

25 |

80 |

52,76 |

13,99 |

Fig. 1. Correlation coefficients among test variables.

Fig. 2. Correlation coefficients among test variables.